UNLV lab studies links between music, child development

At just 9 months of age, Keira O'Brien already is quite the astute music listener.

Not that she's particularly aware of it. All Keira -- a cute, friendly kid who obviously loves nothing more than getting out of the house to meet some total strangers -- is doing is sitting on her mother's lap and watching tiny faces of Elmo from "Sesame Street" emerge from the top bar of an animated T.

But as she watches -- and here's where Keira's nascent music-listening skills are kicking in -- she's anticipating the side of the bar from which Elmo will emerge, based on the melodies she hears right before it happens.

That's pretty impressive for someone her age, notes Erin Hannon, an assistant professor of psychology at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, who has been studying the links between music and child development for about a decade.

While most adults probably take music for granted, Hannon suspects it plays a role in everything from a child's language development to the development of motor skills to even how children adapt to the culture in which they live.

At UNLV's Auditory Cognition and Development Lab, "we do all kinds of research," Hannon says, "but most of it focuses on what children know about sound and how they learn about music and language."

And, she adds, "we think music is important, especially early on."

Mothers seem to intuitively understand it. Think, for example, of the sing-songy way in which many moms talk to their babies.

"I think there are probably some interesting discoveries to be made about how mothers use music to optimize learning during infancy," says Hannon, whose own artistic resume includes playing the piano during high school, singing in ensembles during college and now dancing for fun.

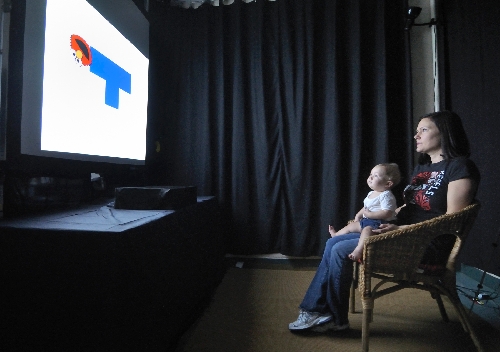

Keira and her mom, Lahaina O'Brien, stopped by to participate in a study that explores whether infants are able to discriminate among, categorize and group different melodies. Keira and O'Brien take seats facing a large screen. On that screen, they'll watch animated images of a ball entering the bottom stem of a T-shaped figure. The ball then will exit the T on either end of the upper bar, turning into the face of Elmo as it exits.

However, each rising ball also will be accompanied by one of several five-note melodies, each of which has a specific "melodic contour," or "the shape of the melody," as made up of rising versus falling pitches, Hannon says. "Usually, when we don't know a song very well, the first thing we pick up is that contour."

With melodies that share similar melodic contours, the ball-turned-Elmo will exit the T on the right side of the crossbar. With melodies that share opposite melodic contours, Elmo will exit on the left.

"We train (infants) to expect Elmo to emerge, depending on the melody," Hannon says. "Then, what we look for is the anticipatory gaze toward the location where Elmo is supposed to come out."

The goal, Hannon says, is "to find out whether babies of a certain age have a sort of categorization for melody, such as down-and-up or up-and-down. That might seem simple to you, but it's actually a level of abstraction animals can't deal with."

Keira, sitting on her mom's lap, views a total of 57 slides while lab manager Parker Tichko and Hannon watch on a monitor that enables them to see Keira's gaze. By the end of the session, when Keira has become antsy enough to call it a day, she has, in several cases, seemed to anticipate where Elmo would appear based on the melodies she heard.

This particular study is one of several being conducted at UNLV that are designed to offer clues about how children process and learn how to use language. Hannon says children are recruited for this study and others through a variety of sources, including referrals from parents who already are in the program to mommy mixers and other events around town.

"We're looking for, basically, children 2 months to 12 years," Hannon says. For information about participating, visit Hannon's website (http://faculty.unlv.edu/ehannon/Home.html).

O'Brien says she learned about the research through a mommy mixer and volunteered because the sessions are a good opportunity for Keira to meet new people and become accustomed to new environments. This marked the second trial in which Keira has participated, and O'Brien says Keira seems to enjoy them.

"She enjoys getting out and seeing new people," O'Brien says, and likes playing with the toys in the next room, too.

"We try to make it as fun as we can," Hannon says. "We try to make it an experience in the same way as an outing."

But while this has been just a fun afternoon out for Keira, the research in which she's assisting can help to discover how music helps to shape children. It may, in fact, even give cause to believe that cuts in funding for arts and music education are, Hannon says, "very shortsighted."

"OK, we want to improve kids' academic skills. That would help our society in general," Hannon says. "But we really don't understand the long-term benefits of musical behavior.

"So I think until we know more about the potential benefits of music, we're wasting an opportunity."

Contact reporter John Przybys at jprzybys@ reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0280.