Penn & Teller’s ‘Tim’s Vermeer’ shows the blood, sweat, tears in detail

The mystery surrounding 17th century Dutch artist Johannes Vermeer’s use of light and how he was able to produce such photorealistic paintings has baffled art historians for centuries.

Some, including artist David Hockney and professor Philip Steadman, suggested he must have used a primitive optical device such as a camera obscura.

Then Texas inventor Tim Jenison came along and not only offered the most compelling theory yet, he set out to prove it by re-creating Vermeer’s “The Music Lesson” despite having zero experience as a painter.

Cracking the case, though, may have been the easiest part of the process behind “Tim’s Vermeer,” the documentary opening Friday that was narrated by Penn Jillette, directed by Teller and executive produced by both.

The Rio headliners changed the structure of their film several times, threw out elaborate set pieces and kept scaling back their onscreen involvement.

“I really thought maybe this was all from Penn’s point of view … about his friend and his friend’s character,” Teller says. “We shot the entire story told by Penn, looked at it, and said, ‘Nope, nope, nope, nope.’ ”

That’s just some of what went into boiling down 2,400 hours of footage from the project that spanned 1,825 days into a funny, awe-inspiring 80 minutes.

And that was after Jillette did everything he could to get out of making the movie at all.

Several years ago, during a particularly busy stretch when he was consumed with work and family — “I didn’t have any social conversations for months,” he says — Jillette reached out to his good friend Jenison, who flew from his home in San Antonio to have dinner in Las Vegas.

“I gave Tim a task,” Jillette says. “I said to Tim, ‘Talk to me about something that can’t possibly have anything to do with work, that can’t possibly have me being interviewed or working or doing showbiz stuff at all.’ ”

So Jenison began recounting his interest in Vermeer and showed Jillette a video demonstrating the technique he concluded Vermeer must have used.

“I guess he probably went on for about 45 minutes before I said anything,” Jillette says, “and the first thing I said was, ‘Well, Tim, you failed. You have not talked to me about something that has nothing to do with work. We’re going to make a movie about this.’ ”

Despite Jenison’s protests that his project was only worthy of a couple of academic papers and a short YouTube video, the next day they were pitching it to the likes of Discovery Channel and the BBC.

“I knew that what Tim was doing was just beyond beautiful and would be fascinating and great. But I was trying to pawn it off on someone else. That was my goal,” Jillette says, blaming his hectic schedule.

After a couple of months, though, he decided that anyone else would just mess up Jenison’s vision. Plus, he was tired of pitch meetings. So they brought in Teller to direct it, and the trio financed the project themselves.

“Technology allowed us to take five years to make a movie … and do it on a budget that successful people can pay to do. Not a studio,” Jillette says. “That means it cost as much as a house, but it does not cost as much as a town.”

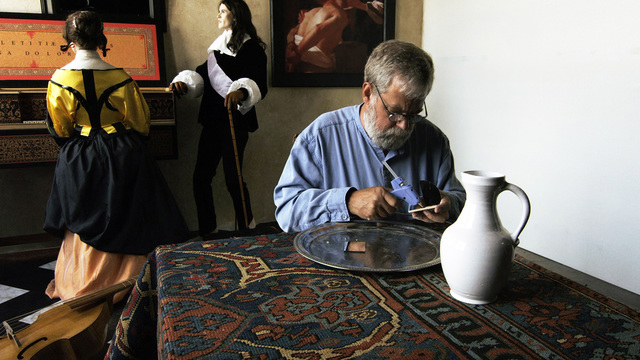

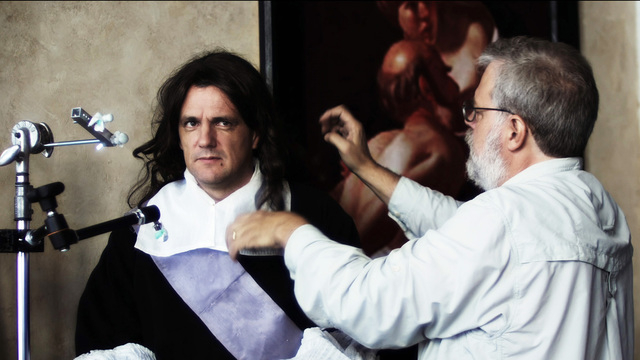

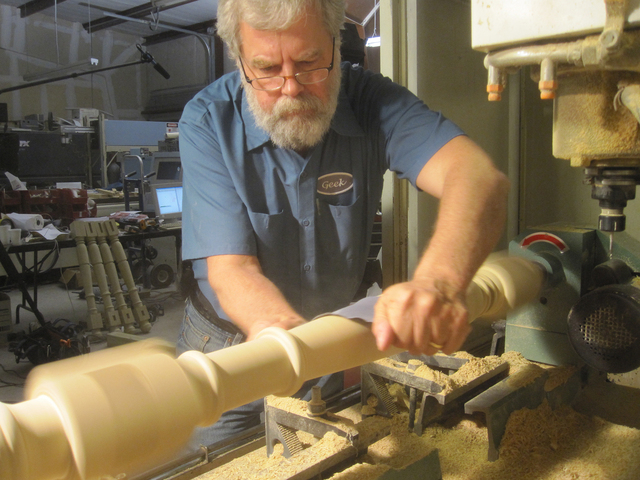

To bring his vision to life, Jenison learned how to make 1600s-style lenses, paints and pigments. He spent 213 days creating a room exactly like the one depicted in Vermeer’s work, down to crafting the furniture himself. And when the lathe he taught himself to use wasn’t big enough for a particular project, he sawed it in two and went back to work. By the time he unpacks a viola like the one featured in the painting, you’ll be stunned and a little disappointed that he didn’t make that by hand, as well. Although he does pick up a bow and crank out a passable rendition of “Smoke on the Water.”

Then, the real work began.

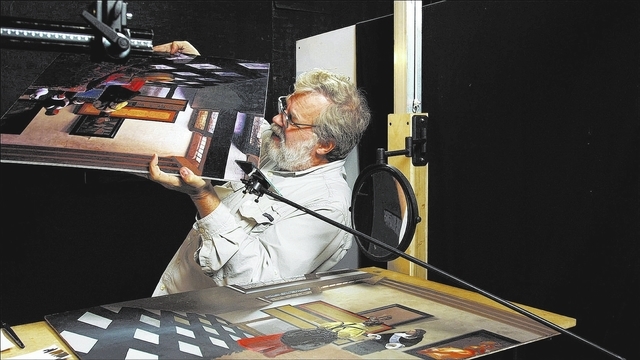

Every morning, Jenison would set up an array of anywhere from three to nine cameras to capture whatever he planned to paint that day — “He’s even more of a one-man band than you realize in the film,” Teller says — before settling in for the painstaking process of re-creating “The Music Lesson.”

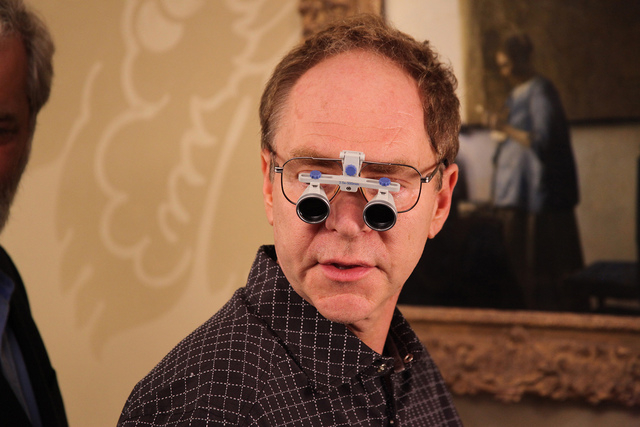

Looking at a small, 45-degree mirror slightly bigger than the ones you’ve had in your mouth at the dentist, Jenison would cover a tiny section, blending the paints until the color on his canvas matched the color of the chair, viola, tapestry or whatever piece of the room he was focusing on that day. When the edges of the mirror seemed to disappear into the canvas, Jenison moved on.

And on.

And on again, for as long as his back and shoulders would hold up.

For 130 days.

“You get some sense of how physically taxing this was,” Teller says. “When he would be working, hunched over that canvas, he’d be able to work for 10, 15 minutes at a time. And then he’d have to straighten up, get up and walk around the block, and come back and do some more.”

In some of the reality show-style confessional interviews, Jenison looks like something out of a hostage video. On Day 82, he experiences what he calls “a wave of revulsion” and wants to quit.

The process itself is so captivating, it led the filmmakers to cut themselves out of much of the finished product.

“We wrote all these Penn &Teller bits, and then we kept watching the footage come in, and we finally said, ‘You know, it really has to be about Tim,’ ” Jillette says. “It’s not about Penn &Teller, and it’s not even really about Vermeer. It’s really about Tim.”

Even then, though, the duo wasn’t sure what they had.

“All my pencil calculations were based on, how do we get this done and then sell it as a one-hour special to TV here and overseas and break even,” Jillette admits. “The idea of a theatrical release was never really talked about seriously.”

Sony Classics persuaded them to think bigger, and “Tim’s Vermeer” became a hit on the festival circuit. After its premiere at Colorado’s Telluride Film Festival, Penn &Teller were introduced to what Jillette calls “very nice applause.” Then Jenison was greeted with a “standing ovation that could not be stopped,” Jillette says. “And we unveiled Tim’s painting, it was a (expletive) stampede. … They just wanted to get close to that painting.”

“Tim’s Vermeer” would go on to be one of 15 feature documentaries shortlisted for last Sunday’s Oscars and one of five nominated for the BAFTA Awards, the Oscars’ British counterpart.

That’s despite its being very different from your typical documentary.

“Documentaries, you know, are supposed to be Michael Moore. They’re supposed to be outlining stupidity and injustice and suffering and overcoming obstacles,” Jillette says. “And if anything, we kind of played down Tim’s work and suffering. … Even when Tim’s bitchin’, we know we’d like to be doin’ that bitchin’ ourselves.”

For his part, Teller doesn’t even like the word “documentary.”

“I think Walt Disney had kind of the right idea when he used to show those nature films on his TV show, and he would call them ‘true-life adventures.’ So I would like to call this a true-life adventure. It’s much more accurate about how you feel about it. When you sit through this movie, at the end, you feel like you’ve been through an adventure. It’s a detective story. It’s a physical challenge. It’s an unbelievable intellectual achievement.”

It’s also an emotional journey, even for the people who lived it.

“The three of us, every time we watch it, we cry,” Jillette acknowledges. “When he finishes that painting, it just rips my heart out.”

Contact Christopher Lawrence at clawrence@reviewjournal.com or 702-380-4567.