CCSD administrators hiring outpaces teachers over past decade

The number of administrators in the Clark County School District has ballooned over the past decade, while the number of teachers has remained almost flat in an era of declining enrollment, a Las Vegas Review-Journal analysis of district data shows.

The ranks of administrators grew by 13 percent from 2014 to 2023, while those of teachers and other non-administrative licensed personnel, such as school counselors, increased by just 2 percent, the data obtained through records requests shows. About 1,700 personnel were in administrative positions in 2023, and 24,300 in teaching and licensed positions, including substitute teachers, many of whom were not full-time employees.

The research director for a Nevada think tank said the district should prioritize spending on student instruction.

“I’d like to see the bulk of resources used where they matter most, which is in the classroom,” said Geoffrey Lawrence, director of research for Nevada Policy, which scrutinizes government spending.

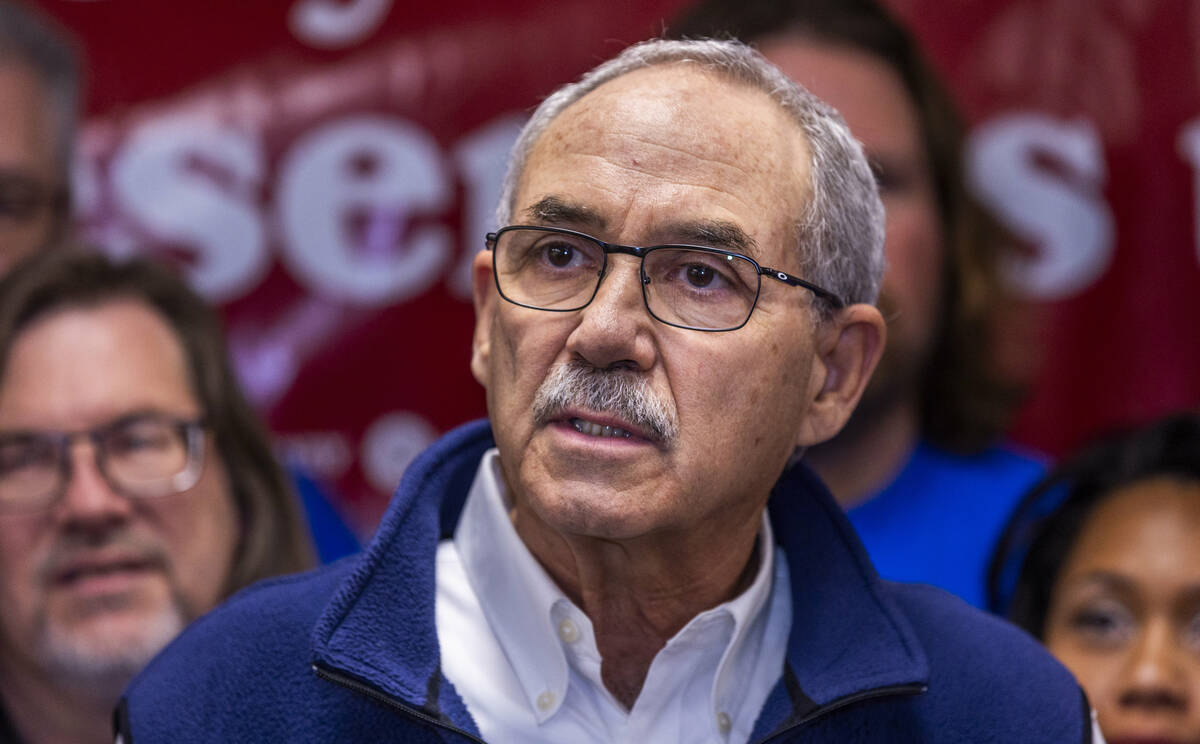

However, new responsibilities have created a need for more administrators, according to the head of the local administrators union.

For instance, the greatest share of an assistant principal’s time is now spent investigating bullying complaints, said Jeff Horn, executive director of the Clark County Association of School Administrators and Professional-Technical Employees.

There were 12,153 complaints of bullying, cyberbullying and racially motivated incidents reported in the Clark County School District during the last school year, according to data posted by the Nevada Department of Education on its Nevada Accountability Portal. That averages out to one complaint for every 24 students.

Of these, 7,190, or 59 percent, were confirmed upon investigation.

Investigations follow protocols outlined under Nevada law, Horn said.

About 295,300 students were enrolled in district schools in 2023, a decline of 6 percent over the decade, according to Nevada Department of Education data.

“This is a policy choice that we are making to spend more money on administrators than in the classroom, and maybe bullying is part of that,” Lawrence said. “But we have to realize there is a trade-off in terms of what we’re giving students.”

Just 50.3 percent of K-12 education spending in Nevada is on instruction, he said, which is slightly below the national norm of 53 percent, according to a 2023 report by the National Center for Education Statistics citing 2021-2022 data. The remainder is spent on expenses such as administration, support staff, operation and maintenance, student transportation, food services, capital expenses and interest on debt, the data shows.

Filling teacher vacancies

Asked to comment on the disproportionate increase in administrators, the district said the data reflected staffed — not budgeted – positions, with some budgeted positions for teachers going unfilled.

The district had more than 1,000 teacher vacancies before the start of the school year, the district said in July.

The district also had nearly 3,800 substitute teachers last year who made between $65,000 in pay and benefits to as little as $23, the data shows. Substitute teachers can teach with an associate’s degree while full-time teachers must have a bachelor’s degree, complete a teacher preparation course and state exams, according to the Nevada Department of Education website.

Filling these vacancies is hindered by a national teacher shortage, the district’s communications office said in an email this month.

“CCSD continues working to recruit and retain licensed educators,” the email stated.

The district initially refused to provide the data as the Review-Journal requested. When it did, it miscategorized some administrative positions. After the newspaper pointed out the flaws, the district provided new data for the analysis.

Recruiting concerns

Not all educator recruiting efforts have been productive, Review-Journal investigations found.

The district sent 17 recruiters and staff to Miami Beach over the Fourth of July holiday in 2023, at a cost of nearly $40,000, excluding salaries, the Review-Journal reported last year. Just two prospective hires came to a recruitment event, and no one was hired. At a cost of $22,000, the district also sent a team of eight to Hawaii’s Waikiki Beach, where a recruitment event attracted three prospective employees.

One recruitment strategy that is helping to fill teacher vacancies is increasing pay, said John Vellardita, executive director of the Clark County Education Association, the local teachers union.

In 2023, Nevada lawmakers approved about $12 billion in state K-12 education spending for the biennium. District teachers received an 18 percent pay increase over two years. District administrators covered by the administrators union’s contract received 11 percent.

Lawmakers approved $250 million in additional funding for teachers, support staff and school police statewide, most of which went to the Clark County School District. District teachers at low-household-income Title 1 schools, where the vast majority of teacher vacancies occur, received an additional $5,000 in pay, Vellardita said. Special education teachers — which are hard-to-fill positions — also received an extra $5,000. Special education teachers at Title 1 schools received $10,000.

“We are seeing where that has made a dent,” he said.

Administrators ‘underpaid’

Administrators did not get a share of the $250 million.

“Administrators are being well underpaid for the work that they do,” Horn said, adding that this is keeping teachers who are effective leaders from becoming administrators.

Lawrence challenged this assertion.

“There’s no evidence that administrator pay levels are preventing people from moving into administrative roles,” he said. “In fact, the data shows that the number of CCSD administrators has grown more rapidly than the number of teachers.”

Between 2014 and 2022, total pay to district teachers and other licensed personnel increased by 40.6 percent, and to administrators by 37.6 percent, a newspaper analysis of district pay data shows. The analysis excluded 2023 data, which included raises that year for administrators but not for teachers, who received their raises this year, retroactive to July 2023.

In 2022, total pay for administrators was $242 million, with pay and benefits averaging $147,400 per administrator. Pay for teachers and licensed personnel was $2 billion, an average of $84,000 per employee in total compensation.

Horn’s union has commissioned a study on administrator pay, with early findings showing that teachers promoted to assistant principal make less per hour in their new position, despite higher salaries. That’s because teachers work nine months out of the year, whereas assistant principals work 11 months, he said.

The union represents administrators at schools as well as some who work in central administration. It does not represent police administrators or the highest-ranking, highest-paid administrators, such as those in the superintendent’s cabinet, who work at the pleasure of the superintendent.

Superintendent hand outs

Before departing the district early this year, then-Superintendent Jesus Jara handed out raises to 13 of his cabinet members, costing taxpayers more than $323,000 a year, the Review-Journal first reported. The largest was a 40 percent raise of $68,000 to the school police chief.

In his final weeks with the district, Jara also gave new contracts to his top administrators with added benefits that could cost taxpayers $3 million, a newspaper analysis of public records found.

All administrator positions need to be scrutinized, said Vellardita, who would like to see a cap on the number of administrators at schools.

“Is the priority to put a teacher in every classroom, or is the priority to increase administrative staff?” he asked.

The district said state law gives “school principals the autonomy to staff their schools based on the needs of their campus.”

Horn said staffing decisions are made collaboratively with teachers, community members and, at high schools, students.

He added, “I’ve never come across a principal who doesn’t want to lower class size and have a qualified teacher in the classroom.”

Contact Mary Hynes at mhynes@reviewjournal.com or at 702-383-0336. Follow @MaryHynes1 on X. Hynes is a member of the Review-Journal’s investigative team, focusing on reporting that holds leaders and agencies accountable and exposes wrongdoing.