COVID could have imploded projects like Resorts World. Why didn’t it?

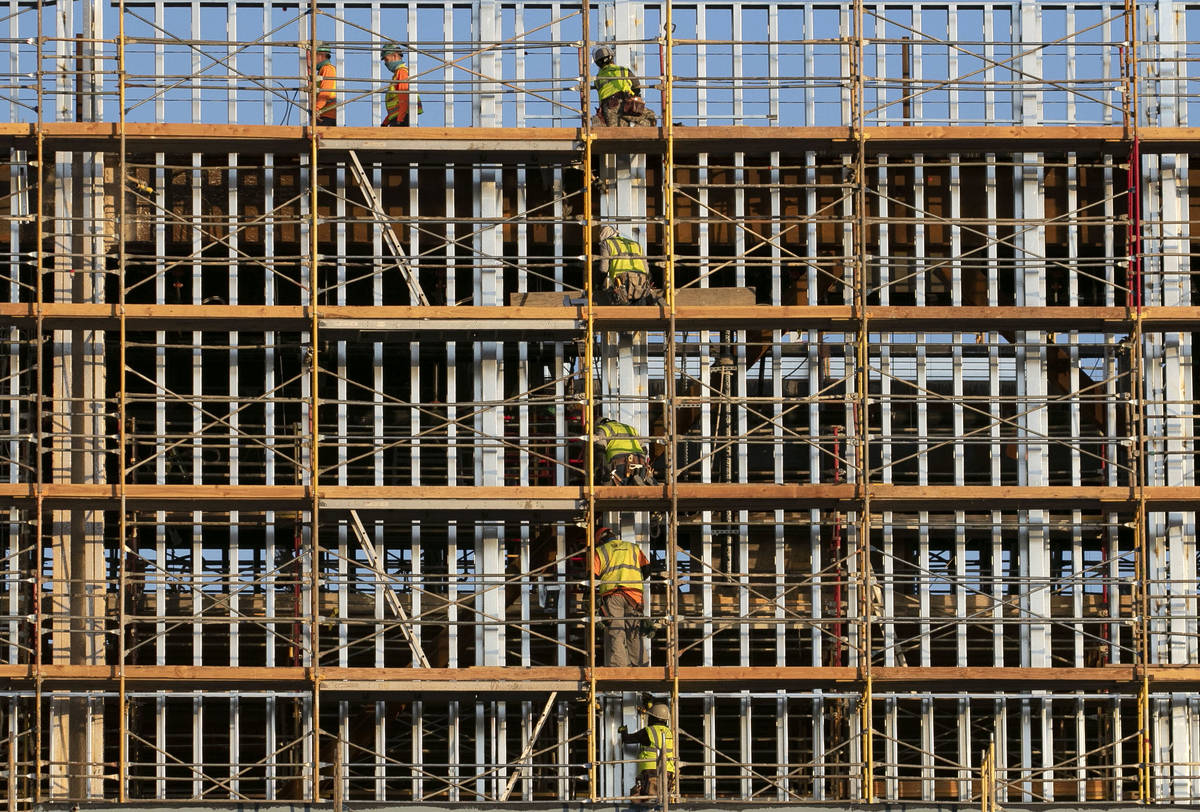

Jutting out from a dirt lot on the Strip’s north end stands Sin City’s newest megaresort in progress.

Set to open next summer, its massive, main tower already swallows a gap of sky between older, squeezed-together high-rises. In swoopy script at its crown, the words “Resorts World” advertise what’s to come.

On the earth below, stacked materials litter the lot next to a sea of backhoes and a colossal crane. “BE SAFE, NOT SORRY,” one sign reads at the main entrance, signed “W.A. Richardson Builders, LLC,” the general contractor for this destination-to-be at 3000 Las Vegas Blvd. South.

“SAFETY IS OUR MOST IMPORTANT PRODUCT,” reads another.

Each day, about 2,200 workers toil away here, according to the project’s website. It’s the largest ongoing construction site in Southern Nevada, a towering example of an “essential” industry whose estimated 72,000 valley workers as of June have not ceased, even as Gov. Steve Sisolak issued a statewide stay-at-home order, casinos went dark and small businesses shuttered amid the coronavirus pandemic.

The special status was considered a victory for the local construction industry, permitted in part because it wasn’t yet clear if temporary treatment facilities would need to be built. It was also a sign of hope — a bet that people would once again attend football games; an assurance that droves of returning tourists would one day make Resorts World Las Vegas a necessity, not just a luxury.

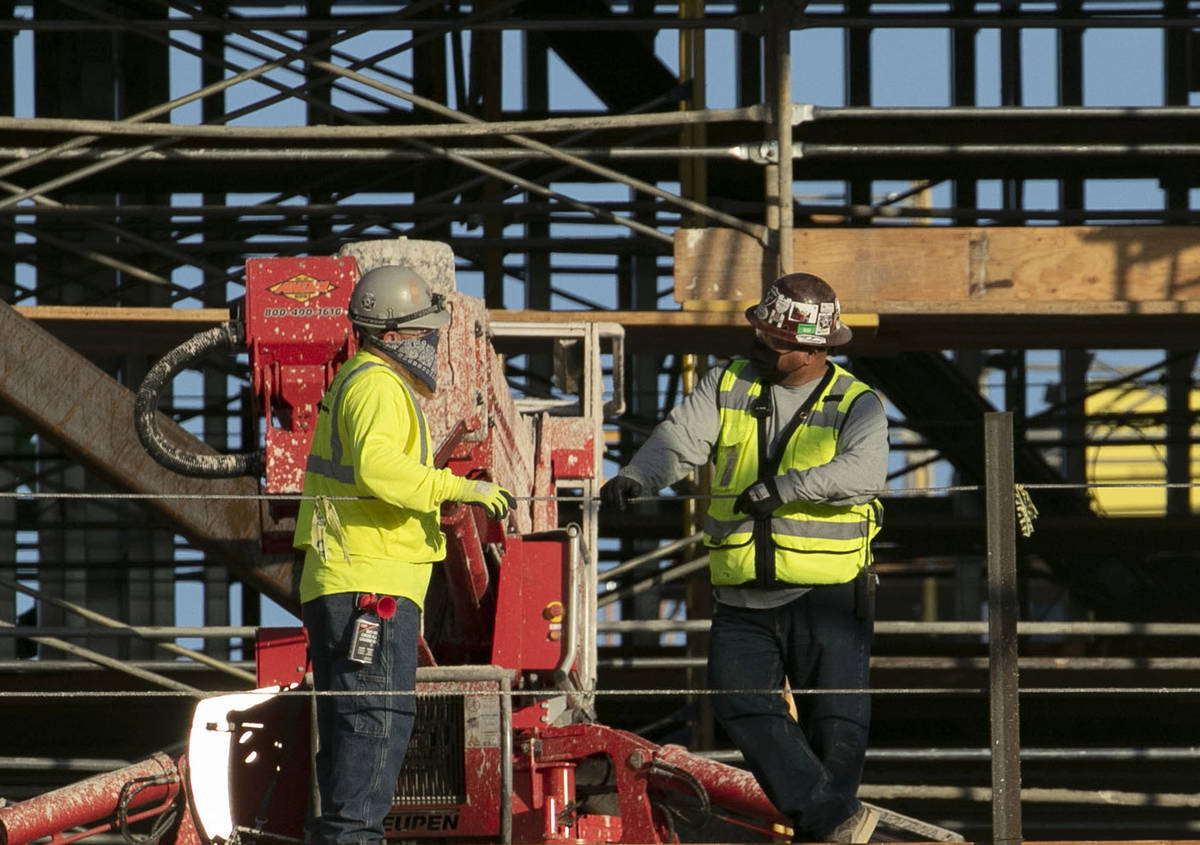

Yet it presented contractors and union representatives with an unprecedented challenge: In a nomadic industry such as this, where workers regularly migrate from job site to job site, and some projects require people to work in close quarters, how do we keep workers safe?

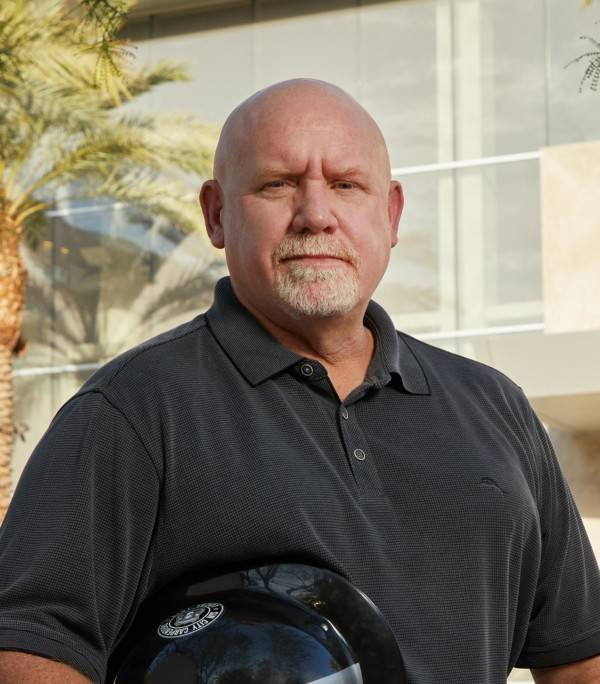

“We went through some real cultural changes to make it happen,” said Frank Hawk, vice president of the Southwest Regional Council of Carpenters and chair of the state’s construction task force on COVID-19 compliance.

Each of about 25 major projects in town is represented on the task force, made up of 19 different industry and union leaders, formed in cooperation with the governor’s office at the start of the pandemic. They have largely worked alone, without state or federal guidance, though they ran proposed changes by Nevada’s Occupational Safety and Health Administration and regularly updated the governor.

Brian Turmail, spokesman for Associated General Contractors of America, said the same can be said of the industry nationwide.

“No federal official said, ‘Here’s the playbook. You need to follow it,’ ” Turmail said. “We essentially wrote it.”

In no way has it been perfect. Local workers have filed safety complaints, and as an industry, construction has seen the lowest rate of OSHA COVID-19 compliance in the state, according to Nevada’s new OSHA COVID-19 dashboard, first published in August. The dashboard does not report the results of follow-up observations, which as of Sept. 2 OSHA said have resulted in zero job-site citations.

Reports of COVID-19 cases have cropped up at Allegiant Stadium and Resorts World, but no centralized, industry-wide case count has been released to the public. So it remains unclear how many workers have fallen ill or died.

In the local carpenters union alone, 38 of about 6,000 members have tested positive, one of whom died, Hawk said. He did not have numbers on hand for other unions. Representatives with Southern Nevada Building Trades and IBEW Local 357 did not respond to requests for comment.

But Hawk, who spoke for the task force, said he is proud of such numbers, which leaders communicate to workers “as best we can.”

“It doesn’t happen by accident, when you have that many people working in close quarters,” he told the Las Vegas Review-Journal, noting that even when workers fall ill, it’s not always known whether they caught coronavirus on the job.

Cross-contamination

An early, obvious challenge in construction was cross-contamination — a huge risk given how common it is for workers to move from site to site as projects are completed.

“Most people have an address where you work, whereas in construction, you don’t,” Hawk said.

Resorts World — a $4.3 billion project by Malaysia’s Genting Group — shares the same general contractor as the Raiders’ practice facility in Henderson, completed in June. Before the pandemic, workers may have reported to the practice facility one day and Resorts World the next.

In what Hawk attributed to early ignorance, and a bit of paranoia, the construction task force’s first strategy called for workers to quarantine themselves before moving to a new site, significantly slowing the constant shifting of labor.

It went far beyond OSHA’s brief, initial protocols for construction, which in mid-March listed protocols that are now considered common knowledge: meeting restrictions, social distancing and access to soap and sanitizer, cleaning supplies and personal protective equipment.

Hawk noted his union donated all of its N95 respirators to medical providers at the start of the pandemic but spent about $195,000 on custom masks to distribute to workers.

“We weren’t in the middle of the mask debate,” Hawk said. “We were saying, ‘You’re wearing a mask. Period.’ ”

Turmail said policies like self-quarantining between sites caused massive project delays across the country and forced contractors to spend much more money to account for the slower pace of labor. But Hawk said no one hesitated.

“That was all self-policed within the industry,” he said of the initial, strict protocols. “It wasn’t like we had a governmental agency telling us to do that.”

In weekly meetings, Hawk said local leaders would report positive cases at sites — two here, three there — then discuss the best way to disinfect the areas and retrace each worker’s steps.

But there was — and still is — no singular place to report such cases to the state or federal government.

“For us we’re thinking, ‘Shouldn’t there be a website or something we report this to?’ ” Hawk said.

A request to speak with the governor’s office was not returned.

As of late, workers must complete temperature checks and a daily health survey before each shift, which asks workers if they have been in contact with anyone suspected or confirmed to have COVID-19.

Records show the Resorts World site has also implemented “close contact permits” for people who need to work within 6 feet of each other. If a worker tests positive, anyone they share a permit with is ordered to quarantine for 14 days unless they receive a negative test.

Safety complaints

Still, safety complaints have trickled in. Since the start of the pandemic six months ago, Nevada OSHA received at least five about the Resorts World site alone, each of which mentioned concerns about the spread of COVID-19.

On March 18, one worker reported there were “no hygiene products on the construction site such as toilet paper, hand sanitizer, and soap for handwashing,” records show.

Another, filed April 1, reiterated those concerns specific to the basement area of the site but also expressed concerns about crowded elevators despite social distancing protocols.

In written responses, the general contractor’s safety director, Shelby Burton, attributed the lack of soap and sanitizer to worker theft, noting that the company since had hired 50 additional workers to monitor portable restrooms and hand-washing stations, which since had been placed in the basement.

Turmail said that nationally, in March and April, such theft was common at construction sites but added that it “wasn’t necessarily workers; it could have been someone walking by at night.”

Like W.A. Richardson Builders, many hired additional staff and stocked up on materials.

The contractor also limited elevator rides to a handful of workers. But on April 9, a third complaint noted that “employees are now crowding into stairwells at the end of the shift.”

Burton told OSHA that employees monitor man lifts and stairwells at the beginning and end of shift to enforce social distancing protocols.

Despite the complaints, W.A. Richardson Builders saw no OSHA violations. The contractor declined comment, citing a contract that states only the project’s owner may speak to the press.

In an emailed statement, Resorts World Las Vegas said in part, “We continue to follow CDC guidelines and OSHA safety standards.”

Case counts still unclear

In its response, Resorts World Las Vegas did not address questions about case counts at the site.

OSHA records dated April 8 identified three positive cases. On April 23, the Review-Journal reported seven positive cases at the site. Records showed no recent totals.

For months, state and local health officials have not identified any specific COVID-19 spreading events or case clusters in Southern Nevada beyond those at nursing homes and other state-licensed facilities.

In its statement, Resorts World cited independent, company-driven contact tracing separate from the local health district.

Hawk, with the carpenters union, said that’s important because health district contact tracing among construction workers has been virtually nonexistent — a problem not unique to Las Vegas. The same could be said for Phoenix and Los Angeles, he said, speaking as a regional head whose work spans the Southwest.

Southern Nevada Health District spokesperson Jennifer Sizemore said in a statement that at one point there was a contact tracing backlog, but she added that the district is “working to investigate all cases and notify all close contacts,” including cases specific to Resorts World.

Hawk said he diligently tracks cases among members. His union offers workers who test positive $500, both to assist them and incentivize them to self-report. Most carpenters who have tested positive are back on their feet, he said.

As chair of the construction task force, Hawk said he is not aware of any major cluster at a job site in Nevada.

Turmail, with the national contractors association, reported the same nationally.

“We’ve had instances of people showing up with coronavirus, but we haven’t seen outbreaks like other industries, like meatpacking plants,” Turmail said.

Rachel Crosby is a member of the Review-Journal’s investigative team, focusing on reporting that holds leaders and agencies accountable and exposes wrongdoing. Contact her at rcrosby@reviewjournal.com or 702-477-3801. Follow @rachelacrosby on Twitter. Subscribe here to support our work.