Dozens of worried families could be displaced as city ends housing program

This house changed everything for Ursulia Christmas.

“It was awesome,” said the 48-year-old single mother of six, reminiscing when she first moved in. “I saved money. I was able to get my kids the things they wanted. Put them through basketball, baseball.”

Christmas has rented the four-bedroom Lone Mountain home from the city of Las Vegas since 2011. Her walls are covered with family photos, honor roll certificates and other mementos. She put a swing set in the backyard. It’s just one of hundreds of properties the city purchased during the Great Recession as part of a federal program aimed at filling abandoned homes.

“Who would give this up?” Christmas said.

Then the letter arrived.

A notice in the mail in mid-May informed Christmas that the city had been authorized by the Department of Housing and Urban Development to sell her house. It was not a notice to vacate, but the letter strongly suggested she would eventually have to relocate.

Now, Christmas and her children are among dozens of families fearing housing insecurity and possible displacement as Las Vegas shutters the federally funded housing program. Once overseeing hundreds of properties, it’s in the process of selling its final 61 homes.

Relocating would require the family to navigate a volatile housing and rental market: Though mortgage rates have decreased slightly in recent weeks, prices are still high and inventory still low.

It’s not just about the cost, though. Christmas’ children range in age from 4 to 27. The three youngest were adopted in 2021, she said, and some of them have special needs. Moving would mean uprooting her children from school, day care and their therapy services. She would have to move farther away from her 73-year-old mother, who has health problems and whom Christmas regularly visits to care for.

“It’s been stressful. I’ve been sick, not sleeping,” Christmas said. “Just not knowing what these people are going to do.”

Response to the housing crisis

The Neighborhood Stabilization Program started in 2008, following the housing bubble bust and financial fallout. In three installments, the program has allocated nearly $7 billion in total to cities and nonprofits nationwide.

Funds could be used for activities including rehabilitating abandoned or foreclosed homes, demolishing blighted properties, redeveloping neighborhoods or providing down payment assistance. But cities had discretion over how they invested the money.

Las Vegas received more than $25 million in NSP funds. Some of that funding went toward helping families purchase abandoned or foreclosed homes, according to Review-Journal stories. But roughly 55 percent of the grant award was used to purchase long-term rental units for lower-income families.

At the program’s height between 2010 and 2012, Las Vegas owned more than a hundred rental properties. Most were located between Tule Springs and Summerlin South — ZIP codes with the highest rate of foreclosure at the time.

Homes were rented to people making 50 percent of the area’s median income or less, documents show. A five-bedroom home could be rented for just $845 a month, according to the website of the Southern Nevada Regional Housing Authority, which the city paid to manage the properties.

Other municipalities used the long-term rental strategy as well: Henderson, for example, gave funds to local nonprofits to purchase and rehabilitate homes for rent. Kathleen Richards, a Henderson spokeswoman, said there are 23 NSP homes in Henderson that are still operating as affordable housing units.

Las Vegas residents said the NSP gave them a chance to elevate themselves financially while boosting their quality of life. And before this year, homes were only sold after the tenants moved out voluntarily, said Kathi Thomas-Gibson, director of Community Services for the city.

Then in 2019, Thomas-Gibson said, the city received instructions from HUD to close the program “expeditiously.”

“It was always designed to be a temporary program,” she said.

Christmas and several other residents swear that they were told by a Housing Authority representative they would never be forced to relocate when they moved in more than a decade ago. Others say they always knew they would eventually have to leave. None of the residents interviewed for this story has documents detailing promises to stay at the property.

Either way, the NSP is ending at a time when home values are inflated and affordable housing is scarce, putting residents on edge. They are finding that their own homes have skyrocketed in value since they first moved in.

The city bought Christmas’ home for $140,109 in December 2009, for example. But today, the house is likely worth at least double that: In 2019, the house next door sold for $307,500. Zillow estimates the market value of Christmas’ home could be around $471,000.

Profits from sales of the homes will go toward other affordable housing programs, including future developments, Thomas-Gibson said. But that is little consolation to the NSP residents who want to stay in their homes.

The situation is part of a broader crisis of affordable rental units, experts say. The residents have grown to rely on a makeshift solution to a “festering problem.” Southern Nevada faces an estimated housing shortage of more than 80,000 units.

“It’s really a larger problem that people across the country are contending with right now,” said Tammy Leonard, an economist and professor at the University of Dallas who studied NSP activities in her city. “It’s a failure on all fronts, that we still have affordable housing problems across the United States.”

Delays in information

For more than a month after receiving the letters, residents said they struggled to learn any details as they called multiple local agencies.

Lack of information led to several residents fearing the worst. Many began to frantically search for new places to live and were immediately daunted by high rental prices and application fees.

“No one has a lot of information to give,” resident Timesha McCullah said in early June. She has three children and has lived in her NSP house for four years.“You would think they would have more info to provide us with before they sent out the letters.”

Clifton Mims, a 62-year-old retiree who lives in his NSP with his teenage son, said he began looking to move out of state.

“I’m struggling now,” Mims said in June. “They’re not giving me the information I need to do anything else.”

Residents called the Housing Authority — their point of contact for everything from rent to maintenance, up until now. Some showed up at board meetings to implore officials for information.

Lewis Jordan, the agency’s executive director, said in June that the Housing Authority was “in contact” with the city and knew about eventual plans to sell the NSP homes. But leaders of the agency still couldn’t give the tenants any guidance.

“It definitely wasn’t something that we knew about, before it started happening, before we started hearing from the tenants,” said County Commissioner William McCurdy II, who serves as vice chairperson on the Housing Authority board.

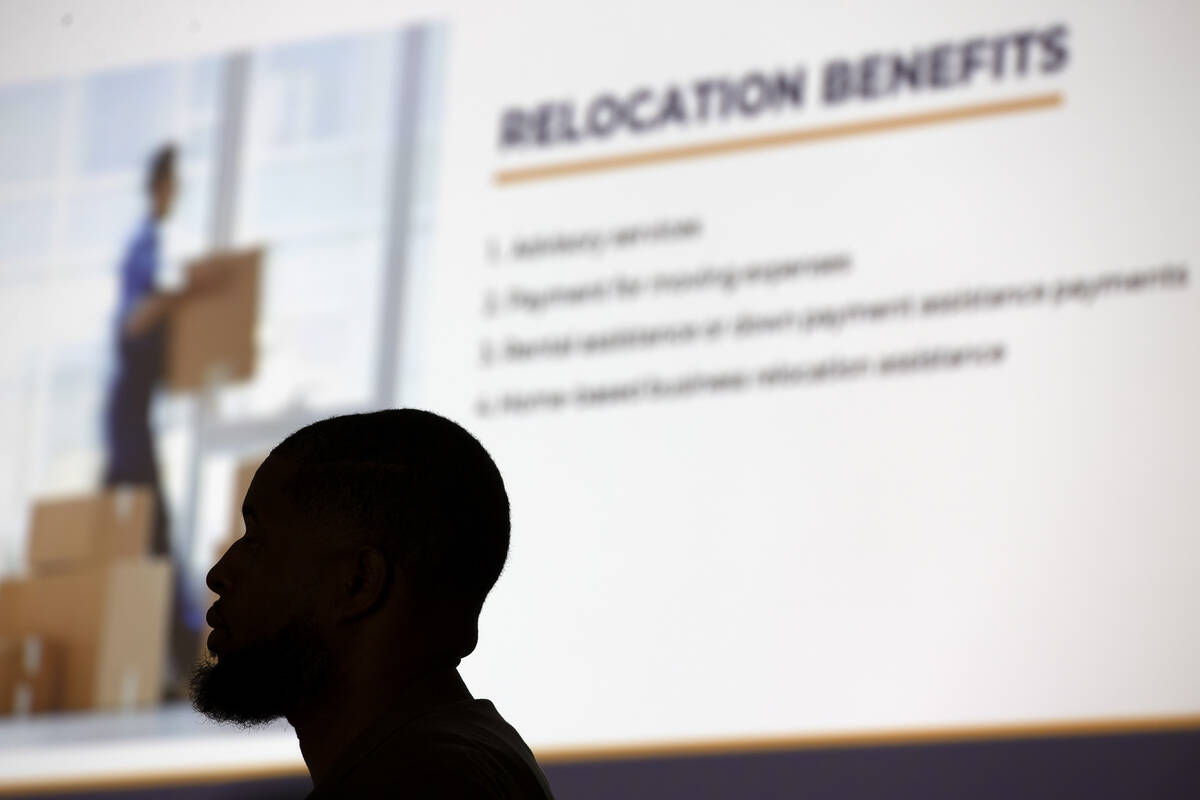

Information seemed elusive until the end of June. That’s when, on a torrid Thursday evening, about 60 people gathered in a Centennial Hills community center for a meeting.

The lights were turned off to keep the room cool. The mood was tense, apprehensive.

Leading the meeting was Del Richardson & Associates, a public affairs and community services firm the city is paying up to $400,000 to coordinate the families’ relocation. The company’s contract started in January, records show, but this was its first meeting with residents.

The presentation had barely started before the crowd interrupted, impatient for answers.

“What is it all for?” a man near the front called out. “We pay our rent. Don’t you think we’ve been through enough already?”

For more than two hours, residents displayed frustrations about the confusing process and questioned what would come next. Several noted the majority of those being displaced were people of color.

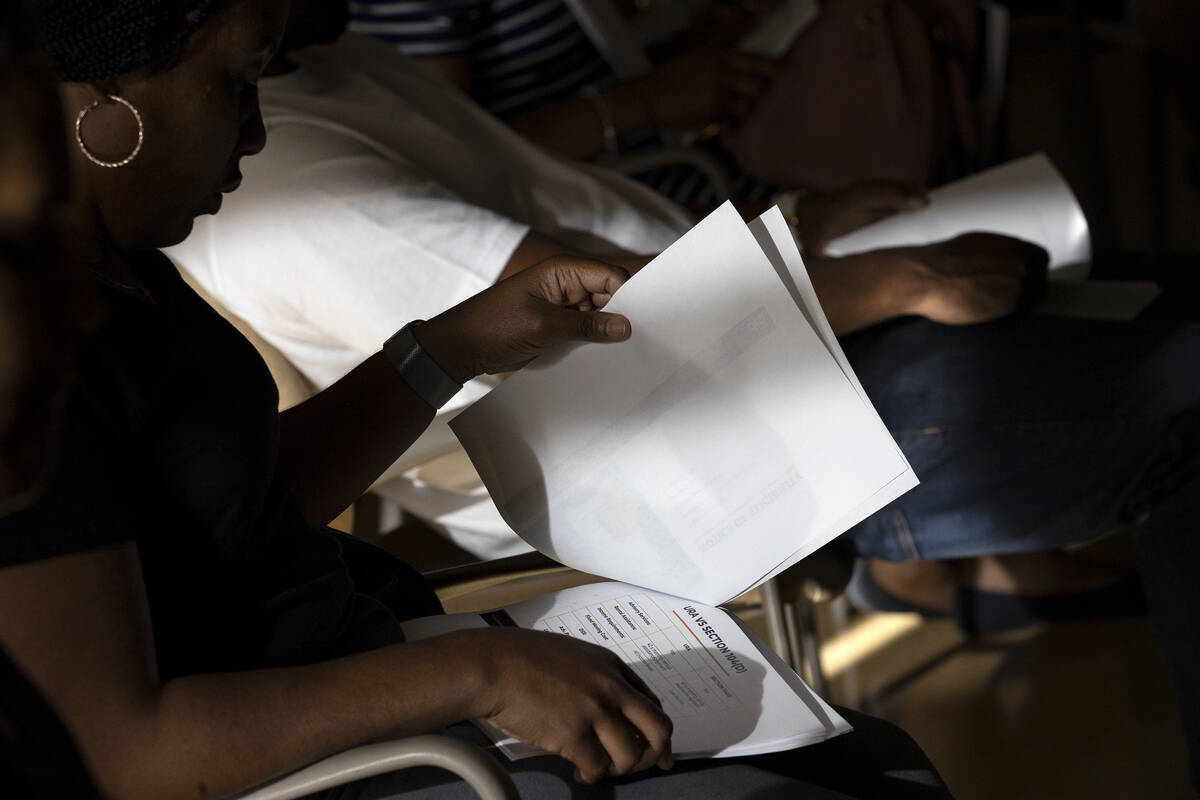

DRA staff assured residents the firm could help them with moving expenses, rental or down payment assistance. The firm would handle all house hunting, one staff member said, and could even help them move out of state.

They described subsidies from the federal government and nonprofits, as well as services DRA offers in financial strategy, credit-building and workforce development. Tenants would receive another notice in the mail to determine their eligibility for services.

“Everything is case by case,” said Taurean Gordon, DRA’s CEO, who described the timeline for the transition as “end of the year-ish.”

“Per person, it might go longer,” he said.

By the end of the evening, many in the crowd were relieved to learn of the options available, but several were skeptical of the firm. Many were still in shock over being asked to leave their homes.

“We felt like we won the lottery,” one woman in the crowd said. “And now you’re taking it away.”

‘Standstill’ for residents

With the end of the federal program, city officials say the situation is largely out of their hands. Any unused grant funds could be “recaptured” by HUD.

“It’s not really like the city has a choice in this,” city of Las Vegas spokesman Jace Radke said.

Thomas-Gibson said it’s their priority to lessen the blow to residents, which is why DRA was hired.

“We told DRA that every tenant must have a positive outcome,” she said. “Each family gets an individual plan tailored to their particular household.”

Since that meeting at the community center, DRA staff met with residents individually, where they completed questionnaires to describe income and housing needs. But there is still no timeline for when or if tenants will have to move. Radke said DRA will provide a written update on its progress by December.

But in the interim, residents are feeling restless. McCullah said it feels like everything is at a “standstill.”

The prolonged uncertainty is only compounding residents’ fears. Mims said he felt like DRA was brought in just to “pacify” the crowd. Meanwhile, he is trying to get his old job back, coming out of retirement to work as a ticket writer and supervisor for William Hill. He is still considering a move out of state.

“I’m still in limbo,” he said. “I don’t know what’s going to happen.”

Christmas said she has visited a hospital twice after experiencing panic attacks.

“We don’t know what’s going on,” she said. “We’re thinking we’re just going to be put out. … Sometimes I just get tired. Some days I try not to even worry about it, but we know that date’s coming.”

Contact Teghan Simonton at tsimonton@reviewjournal.com or 702-477-3850. Follow @teghan_simonton on Twitter.