Influencer payments hidden from taxpayers

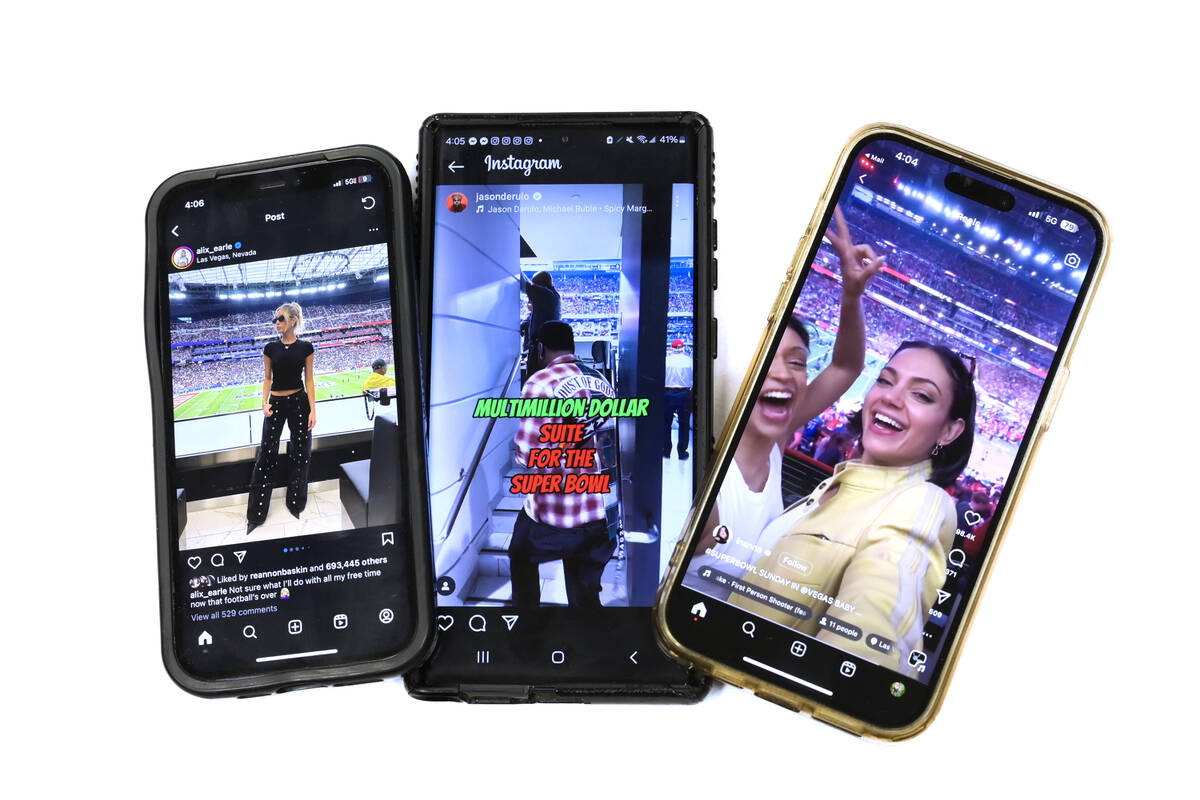

The Las Vegas Convention and Visitors Authority is spending more than $2.2 million on influencers to promote the city, but the taxpayer-funded agency redacted the amount of money each influencer received, calling it a trade secret.

Ben Lipman, chief legal officer at the Las Vegas Review-Journal, said there is no exemption in state law that allows the agency to hide the amount of public money paid to a contractor or vendor.

“That should be public,” he said. “That the amount of money a governmental entity pays to independent contractors is somehow a trade secret is without basis. This is a government expenditure that is quintessentially public information.”

In May, the agency, which had previously been a focus of stories about questionable spending, announced it would give $100,000 to each of the Las Vegas Aces basketball players. LVCVA President and CEO Steve Hill said the agency also has 100-plus influencers on the payroll.

The Las Vegas Review-Journal filed an open records request to determine how much the agency spends on influencers and what taxpayers are getting for their money. The agency has repeatedly delayed releasing the records and only released the contracts with the amount paid redacted.

Hill defended the delays and redactions, saying the agency received a large number of open records requests after the Aces sponsorship deal was announced. He confirmed that the LVCVA believes it can withhold the amounts paid to each influencer under the trade secrets exemption.

“We have been inundated with records requests,” he said. “We had a couple of attorneys look at it, and it is the standard definition of trade secrets.”

Hill, who is paid nearly $600,000 a year in salary and bonus, didn’t know the specifics of the influencer program but declined to make staff who did available, saying he wanted written questions.

Nick Mattera, a vice president at Ykone, the agency that LVCVA hired to contract with many of the influencers, declined to comment, saying he wanted written questions so that they could be “vetted” by the convention authority.

History of lavish spending

In 2017, the agency was the focus of a two-year Review-Journal investigation that questioned its spending of taxpayer resources. Hill was appointed CEO in 2018.

The paper found that LVCVA executives spent money on top-shelf liquor and $300 steaks, gifts for employees and first-class trips for board members, many of whom are elected officials in various local governments. The authority also paid at least $697,000 for alcohol, $85,000 to hire showgirls and hundreds of thousands more for concert tickets, skyboxes, banquets, exotic car rides and jewelry for employees, the Review-Journal found in its analysis of LVCVA records.

Other Review-Journal stories found that convention center security guards were used to chauffeur top agency staff and there were few controls on what staff took from a warehouse of high-end goods intended as gifts for people bringing business to the city.

Then-CEO Rossi Ralenkotter also directed the staff to obtain airline upgrades for his wife from a British Airways executive. The agency then comped meals and show tickets for the airline executive and his family when they visited the city, emails obtained by the paper showed.

The stories sparked an audit, which found that Ralenkotter and other executives used Southwest Airlines gift cards for personal flights, leading to felony criminal charges. The charges were settled with pleas to misdemeanors.

In 2018, Hill replaced Ralenkotter, who received a $455,000 severance package and now gets $305,000 a year in pension. Hill promised transparency and accountability at the embattled agency when he took over.

“We need to be aware of what we’re doing,” he said during an editorial board meeting with the Review-Journal in 2018. “We need to be transparent about it. There are going to be times when we’ll disagree on what our decisions are. Sometimes I may even think you’re right, and we’ll reconsider those. We need to make good decisions. We need to be transparent about them, and we need to instill trust in the organization.”

He contended in July that the refusal to release the amounts paid to influencers was not a failure in transparency or accountability.

Millions for influencers and sports stars

The records request for the influencer payments was filed on May 23, and sought contracts with influencers and any documentation showing that the contracts produced a benefit for the city. Agency staff responded five business days later saying the records were not readily available and would be provided by June 19.

But Lipman said records that are readily available should be produced immediately and agency representatives can only delay release if they are unable to gather the records in the five-day period.

“They can’t delay just because they don’t want to provide them timely or feel it’s not convenient,” he said.

State law requires agencies to respond within five days and provide a date of records production if the documents are not readily accessible.

By June 20, no records had been produced, and the agency sent the Review-Journal a letter saying the documents would be delayed until July 1.

Lipman said agency officials must notify the requester before the deadline that they can’t meet it and then set another date.

That didn’t happen with these LVCVA records.

On July 1, the agency produced a list of 264 influencer names and the total of $2.23 million spent on the marketing, noting that it averaged out to $8,458.84 an influencer. The document did not provide figures for how much each influencer received.

At 6:06 p.m. the day before the July 4 holiday, the agency released about 1,500 pages of contracts with the influencers, but the amounts for each were redacted. The agency cited various laws, but Lipman said the laws do not allow it to withhold the figures paid to each influencer.

A letter attached to the July 3 records release said that additional information about what the influencers provided for the money would be released July 24.

At 6:38 p.m. on that date, an LVCVA employee sent an email saying the records would be delayed until at least Aug. 16 because they include more than 4,000 emails.

The “What Are They Hiding?” column was created to educate Nevadans about transparency laws, inform readers about Review-Journal coverage being stymied by bureaucracies and shame public officials into being open with the hardworking people who pay all of government’s bills. Were you wrongly denied access to public records? Share your story with us at whataretheyhiding@reviewjournal.com

Contact Arthur Kane at akane@reviewjournal.com and follow @ArthurMKane on Twitter. Kane is editor of the Review-Journal’s investigative team, focusing on reporting that holds leaders and agencies accountable and exposes wrongdoing.

Reporter Callie Lawson-Freeman contributed to this story.