Las Vegas developer with close ties to senator lands $37M government contract

State Sen. Dina Neal recused herself from reviewing bids for a $37 million state contract that a family friend was seeking, but she still pushed behind the scenes for him to land the deal, emails obtained by the Las Vegas Review-Journal show.

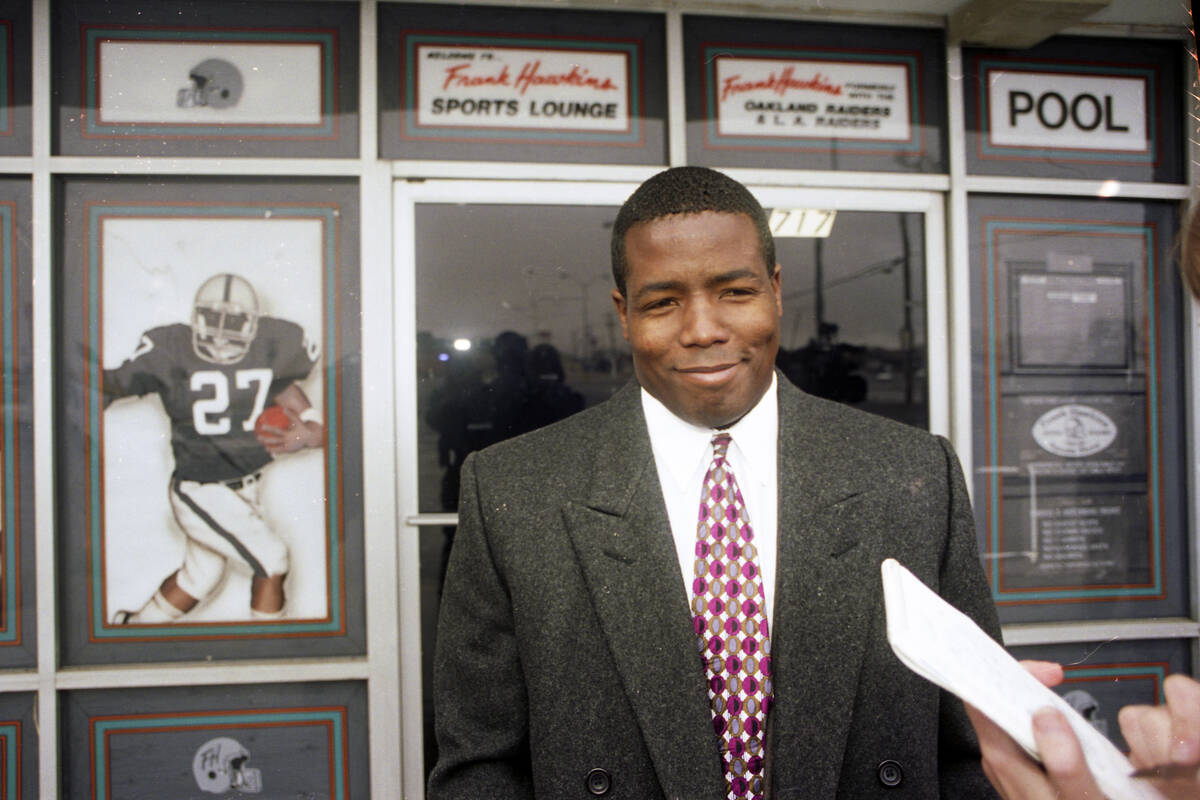

The Nevada Housing Division awarded a contract early this year to developer Frank Hawkins’ company to build a new subdivision for residents of Windsor Park, a sinking neighborhood in Neal’s district. Hawkins, a former Las Vegas councilman and Raiders player, has known Neal’s family for decades, contributed for years to her campaigns and previously employed her.

The state told him he was getting the job three days before it asked members of an advisory committee to vote on whether they approved the pick, emails show.

Nevada officials say the committee was not required to vote on the deal, and of the only two bidders for the project, Hawkins’ nonprofit affordable-housing firm scored higher.

But multiple officials involved with the process had concerns with both bids and suggested releasing the contract again to see if more developers would apply, according to emails obtained from the Housing Division through a public records request.

Neal, D-North Las Vegas, introduced a bill last year that financed the project. She was involved with the contracting process as a member of the Uplift Windsor Park Advisory Committee but opted out of reviewing the bids, citing Hawkins’ friendship with her late father.

Despite that, she told officials about her concerns with the other applicant at least twice, emails show. She also wrote in an email that a “decision to move forward needs to be made” and that she heard Hawkins wanted the job.

“There is only one clear person who is willing to do this work, qualified and will do this,” Neal wrote to Housing Division officials, adding that to “drag this out further is a problem.”

‘Proud to be selected based on the merits’

Hawkins has contributed thousands of dollars to Neal’s political campaigns, and Neal worked for his company, Community Development Programs Center of Nevada, more than a decade ago, the Review-Journal found.

The Review-Journal reported in April that the FBI was investigating whether Neal used her influence to secure federal money for a friend — an allegation first revealed by the newspaper. That investigation was not related to Windsor Park or Hawkins.

Neal and Hawkins contend there were no improprieties in the bidding process for the North Las Vegas project.

“We have always adhered to ethical and transparent practices, and the suggestion that this process was influenced by inappropriate political maneuvering is both inaccurate and disappointing,” Hawkins wrote in a statement to the Review-Journal.

Hawkins, founder and executive director of Community Development, said his company has built numerous affordable-housing projects in Southern Nevada and was “proud to be selected based on the merits of our proposal, our experience, and our commitment to providing quality housing.”

He has known Neal and her family for more than 30 years, and their “professional relationship has always been focused on addressing the needs of underserved communities,” he said.

Neal, who won her re-election primary race this year and is running unopposed in the general election, said in a statement that the contracting process was complete and the committee selected the top applicant.

“You seem to think this is a joke and these are people’s lives you are playing political games with,” she wrote in an email to the Review-Journal.

The senator was part of the advisory committee that helped implement her legislation and was a “key voice” in making sure the spirit and intent of the bill was carried out, said Teri Williams, spokeswoman for the Nevada Department of Business and Industry, which includes the Housing Division.

Neal did not disclose to the division any other ties to Hawkins beyond the family friendship. But the senator and the developer are both “prominent figures and long-time leaders in North Las Vegas,” so state officials “knew there could certainly be a connection between the two individuals,” Williams said.

‘I want Frank Hawkins in that working group’

Windsor Park was built in the 1960s over geological faults, and its homes, roads and utilities started sinking decades ago after groundwater was pumped from an underground aquifer. Neal’s legislation allows remaining homeowners in the historically Black community to exchange their houses for newly built ones nearby.

The bill requires the state to pay for their moving costs, to provide up to $50,000 in restitution and to help arrange financing to pay off their existing mortgages. It also states that the development and construction contracts for the new project “must include a preference” for businesses whose owners currently reside or previously lived in Windsor Park.

Gov. Joe Lombardo signed the measure, Senate Bill 450, in June 2023. It wasn’t long before Neal mentioned a name to state officials.

In July 2023, Neal emailed several questions about the process to the Department of Business and Industry’s then-director, Terry Reynolds, and Housing Division Administrator Steve Aichroth. Among other things, she asked what a potential working group would discuss.

“I want Frank Hawkins in that working group, if it is created,” Neal wrote.

The Housing Division issued a request for proposals in September 2023, saying the developer would need to acquire land adjacent to Windsor Park and build 93 single-family homes that are the same size as Windsor Park’s remaining houses.

Neal was one of several members of the Uplift Windsor Park committee, formed by the division to contribute to the request for proposals and evaluate developers’ bids. Last December, she told officials she did not have a conflict of interest but would stay away from reviewing proposals out of an “abundance of caution.”

She cited Hawkins’ friendship with her father, Joe Neal, who died in 2020 at age 85 and was Nevada’s first Black state senator. She did not mention her other ties to Hawkins.

In a 2011 financial disclosure, Neal listed “Community Development Program Center of Nevada” as a source of income. Her LinkedIn profile says she was a contract administrator there from 2009 to 2011.

Hawkins has contributed to numerous political candidates in Nevada over the years, with at least $6,700 going to Neal since 2009, including $2,000 this past April, campaign finance records show.

Hawkins confirmed to the Review-Journal that Neal previously oversaw administrative tasks for his company’s projects.

He also said he supports candidates and elected officials whose values align with his, including Neal.

‘Not an acceptable ask at taxpayer expense’

The only companies that sent bids for the Windsor Park contract were Hawkins’ firm and Oikos Development Corp., state records show.

Oikos, based in Kansas City, Missouri, proposed building energy-efficient homes and said its total budget was around $35.2 million, including a roughly $3.1 million developer fee. At the time, Oikos said it was working to obtain a Clark County business license.

Las Vegas-based Community Development proposed houses with contemporary designs, energy-saving features, designer lighting and cabinetry, and spiral staircases leading to rooftop patios with views of downtown and the Strip.

It also highlighted the firm’s founder. Hawkins grew up in Windsor Park, played football at the University of Nevada, Reno and was drafted by the Oakland Raiders in 1981. After retiring from the NFL, he became the first African-American ever elected to the Las Vegas City Council, in 1991.

The Nevada Commission on Ethics found that he failed to disclose loans from a company with business before the council — he had obtained the loans before his election — and that he made almost $20,000 from a one-day celebrity golf tournament he hosted in 1994 that included sponsors with business interests in the city. Hawkins lost re-election in 1995 and formed his development company in 1997.

Some outside homebuilders reviewed the proposals for the state and found flaws with both, saying neither “should move forward as is,” emails show.

Oikos did not seem familiar with the local market or provide a site plan, and its “questionable” budget included estimates that appeared either too low, too vague or much higher than usual, according to a Jan. 3 email from Mina Maleki, director of land acquisition and forward planning at Tri Pointe Homes, to Mae Worthey-Thomas, the Housing Division’s then-deputy administrator.

Oikos did not respond to a request for comment.

Hawkins’ firm requested nearly $6 million more than the state-approved budget, “which we believe is not an acceptable ask at taxpayer expense given the specifics of the proposal,” Maleki wrote in the email.

Its homes’ complex footprints would drive up costs “unnecessarily,” the painting costs were “greatly inflated,” and the electrical costs appeared “dramatically higher” than normal, Maleki wrote.

‘I don’t know why they are even being considered’

Two members of the advisory committee volunteered to score the proposals and ranked Hawkins’ bid higher, state records show.

Still, Worthey-Thomas told committee members in an email Jan. 5 that the division was concerned that neither bid showed an ability to develop the project within the request for proposal’s framework.

On Jan. 12, Neal wrote officials in an email that Oikos didn’t have a business license, “so I don’t know why they are even being considered. They don’t have a site plan and various other issues are a problem.”

Hours later, she wrote division administrator Aichroth, Worthey-Thomas and another official in an email that a “decision to move forward needs to be made, it’s been vetted and due diligence has been done.”

“There is only one clear person who is willing to do this work, qualified and will do this. … So to drag this out further is a problem.” Neal wrote. “I heard Frank said he wants to do it, he is choosing to do this work knowing the limited amount.”

She also wrote that the other company had limited experience.

‘If they had to vote it would be for Frank’

On the morning of Jan. 16, Worthey-Thomas told division officials that three committee members expressed concerns with both applicants’ ability “to do the job, but if they had to vote it would be for Frank.”

“All three asked if releasing the RFP again was an option as they feel it would be nice to try to get the RFP out to more developers,” Worthey-Thomas wrote in an email.

But two of them realized the budget wouldn’t change, so all in all, they felt Hawkins “would be the best choice,” given his enthusiasm, presentation and “emotional connection to the community,” she added.

Aichroth replied that this lined up with everyone’s thoughts. Later that day, Worthey-Thomas told Hawkins that the division selected his proposal.

She also shared the news with Neal. “I know Frank. … He won’t fail,” Neal replied.

Three days later, on Jan. 19, Worthey-Thomas emailed committee members to ask whether they “approve of the Division selecting” Hawkins’ firm.

A week after the division reached out to Hawkins’ references, Worthey-Thomas sent him the award letter Jan. 29 officially granting his firm the contract, and the division announced the selection.

The Uplift Windsor Park committee was advisory in nature, and there was no requirement for its members to vote, said Williams, of the Department of Business and Industry.

Hawkins’ firm was awarded the contract based on the strength of its submission and its “ability to address the concerns raised during the process,” she added.

The contract was finalized in May. The $37 million budget calls for $1.75 million in developer profit.

Hawkins said that sum is consistent with industry standards for projects of this scale and that there is no guarantee his firm will make a profit.

The city of North Las Vegas has not received any project plans or applications yet for the new community, city spokesman Greg Bortolin said in mid-August.

Hawkins is looking to acquire vacant land just east of Windsor Park.

Jason Smith, a handyman who has lived in his Windsor Park home since 2017, said the house has shifted and he wouldn’t be opposed to getting a new one nearby.

Burgess Houston III, a carpenter, said that his house was owned by his grandfather and that the foundation cracked.

Still, he scoffed at the idea of moving to a location selected by someone else, and he noted there is violence in the area.

“You think I want to be in the ghetto for the rest of my life?” Houston asked.

Longtime Windsor Park resident Annie Walker, whose name graces a neighborhood park, she appreciates Neal’s efforts. But Walker raised her kids in Windsor Park and is comfortable in her home.

“To be bounced about like a rubber ball, nope,” she said.

Contact Eli Segall at esegall@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0342. Segall is a reporter on the Review-Journal’s investigative team, focusing on reporting that holds leaders, businesses and agencies accountable and exposes wrongdoing.