Nevada cannabis lounges stoke DUI fears as fatal crashes rise

As Southern Nevada expands the places where people can legally get high on marijuana, Las Vegas police are gearing up to stop stoned drivers.

To catch them, they must perform additional field sobriety tests. They’re taking notes: Are the subject’s eyes crossing? Can they keep their balance?

During a recent training course, one patrol officer balanced on one leg and counted to 30. Another watched his partner’s eyes cross as they followed his finger. A third tilted his head back, closed his eyes and touched his nose.

“You guys have a real chance to live up to the oath you took when you started, to really save people’s lives,” Lt. Daryl Rhodes told the trainees. “I’m talking about true victims out on the roadway.”

Rookie officers are learning to detect drug impairment in the police academy, but there are still hundreds more veteran officers to bring up to speed. The monthly courses will continue as Las Vegas and Clark County start licensing marijuana lounges.

Deadly crashes involving marijuana are rising in Nevada. In 2021, 38 were recorded on the state’s roadways, almost double the number in 2016, which was the year before recreational cannabis became legal.

And THC, the chemical in cannabis that gets people high, was present in 70 other fatal crashes where drivers also used alcohol or other drugs, according to the state’s most recent data.

Traffic experts fear there will be more of an uptick after marijuana lounges open in the coming months. Metropolitan Police Department officials say enforcement is paramount.

“The lounges coming online coincides with a change that’s going on not only within our department but that is going on statewide,” said Lt. Bret Ficklin, who oversees Metro’s traffic bureau with Rhodes.

An officer’s proficiency can make or break a DUI case because prosecuting marijuana cases in Nevada is far from an exact science.

Then-Gov. Steve Sisolak signed legislation into law in 2021 that fundamentally changed how the state prosecuted misdemeanor cases. Blood tests can show the drug’s presence in a driver’s system — but that isn’t enough to prove intoxication because the driver might have ingested THC days earlier. A conviction requires other evidence, such as how a person drove and interacted with police at the scene.

Last year, Metro made some 5,800 arrests for DUI, including both drug- and alcohol-related. But some fell apart at the courthouse, traffic intervention officer Mike Thiele said during February’s training.

“We also delivered them some very poor cases on our part,” he said. “We are humans, but we have to deliver the case better.”

Plans for lounges

This year will mark the first time Nevadans can toke up in public.

Both Clark County and the city of Las Vegas have given the green light to marijuana lounges, businesses that will essentially act as bars for cannabis consumption. Las Vegas approved its regulations this week.

UNLV Traffic Safety Coalition coordinator Erin Breen is concerned the lounges will lead to more fatalities.

“Getting behind the wheel of a car when you’re impaired is every bit as dangerous as having a gun in your hand,” she said. “We’re allowing yet another step in the marijuana journey without changing the laws in the state of Nevada.”

To help prevent stoned driving, Clark County regulations require lounges to create impaired driving prevention plans and to adopt a minimum 24-hour no-tow policy for customers who want to leave their cars and return when they’re sober. Establishments also must stop selling marijuana products two hours before closing.

Still, this is unfamiliar territory for officials, county traffic safety director Andrew Bennett said.

“Unlike alcohol and bars, there’s still not a centralized recognized curriculum when it comes to people distributing cannabis,” he said.

Recreational weed is legal in 21 states, 10 of which have approved regulations allowing pot lounges. But only a handful of those states have opened establishments.

If more crashes happen on the roadways and are attributed to the new businesses, Clark County Commissioner Michael Naft, who spearheaded the creation of the traffic safety office, said he would look into re-addressing the policy before the commission. He didn’t say exactly what changes he would propose, but he also is looking at expanding some of the regulations on lounges to include bars and taverns.

Marijuana industry leaders want an “equal, level playing field” with bars, said Brandon Wiegand, president of the Nevada Cannabis Association and chief operating officer of Thrive Cannabis Marketplace.

In December, he told the Nevada Advisory Committee on Traffic Safety that he was looking into products that “eliminate the high” by reversing the effects of THC with an expectation that patrons still won’t drive when they leave.

“There’s not a lot to learn from, and there’s, I think, a wide open blue ocean ahead of us of what that looks like,” he said in a recent interview.

A challenge to DUI laws

The most notable challenge to Nevada’s marijuana DUI laws started more than two decades ago.

In 2000, Jessica Williams drove a van that crossed a median on Interstate 15 north of Las Vegas. She struck six teenagers, killing them all. She told police she smoked marijuana about two hours before the crash and ingested ecstasy the night before.

A jury later determined that Williams was not impaired but convicted her under an aspect of the law that forbids people from driving with a prohibited substance in her blood. She served 19 years in prison.

A federal judge vacated Williams’ convictions in June 2020, ruling that they were based in part on Williams having a marijuana metabolite in her system that was not specifically outlawed.

Her attorney, John Watkins, said she was prosecuted under a flawed law. He said it is still flawed to this day despite some recent changes.

“I was not unmindful of the tragedy that had occurred,” Watkins said. “But Jessica wasn’t impaired. The jury found her not guilty of impairment. She only went to jail because of the numbers.”

The numbers Watkins refers to are the legal limit the law says indicates impairment. Today, that’s 2 or more nanograms per milliliter of THC, or 5 or more nanograms per milliliter of another psychoactive chemical in marijuana.

But the levels of marijuana deemed to be unlawful have no relation to whether one was impaired, Watkins said.

The effects of marijuana can differ depending on the user. A regular user’s blood can contain elevated levels days or even weeks after smoking.

Toxicology reports can be used in court, but it is not enough to prove impairment for misdemeanor marijuana DUIs or DUI cases involving prescription drugs.

Prosecutors also must prove impairment through other means, such as driving behavior and field sobriety tests. But in felony cases that cause injury or death, state law still allows the levels of marijuana in the blood alone to prove impairment.

“That to me is a little irony, a little contradiction,” Watkins said. “The bottom line is that a real good officer is going to be able to detect what he needs to detect.”

Lab results for drug DUIs also take more time than alcohol cases, according to statistics provided by Metro’s lab director Kimberly Murga.

From May to October last year, the lab took an average of 73 days to process drug cases — more than twice as long as alcohol cases. Felony cases are rushed and can take less than a week.

Enforcing the law

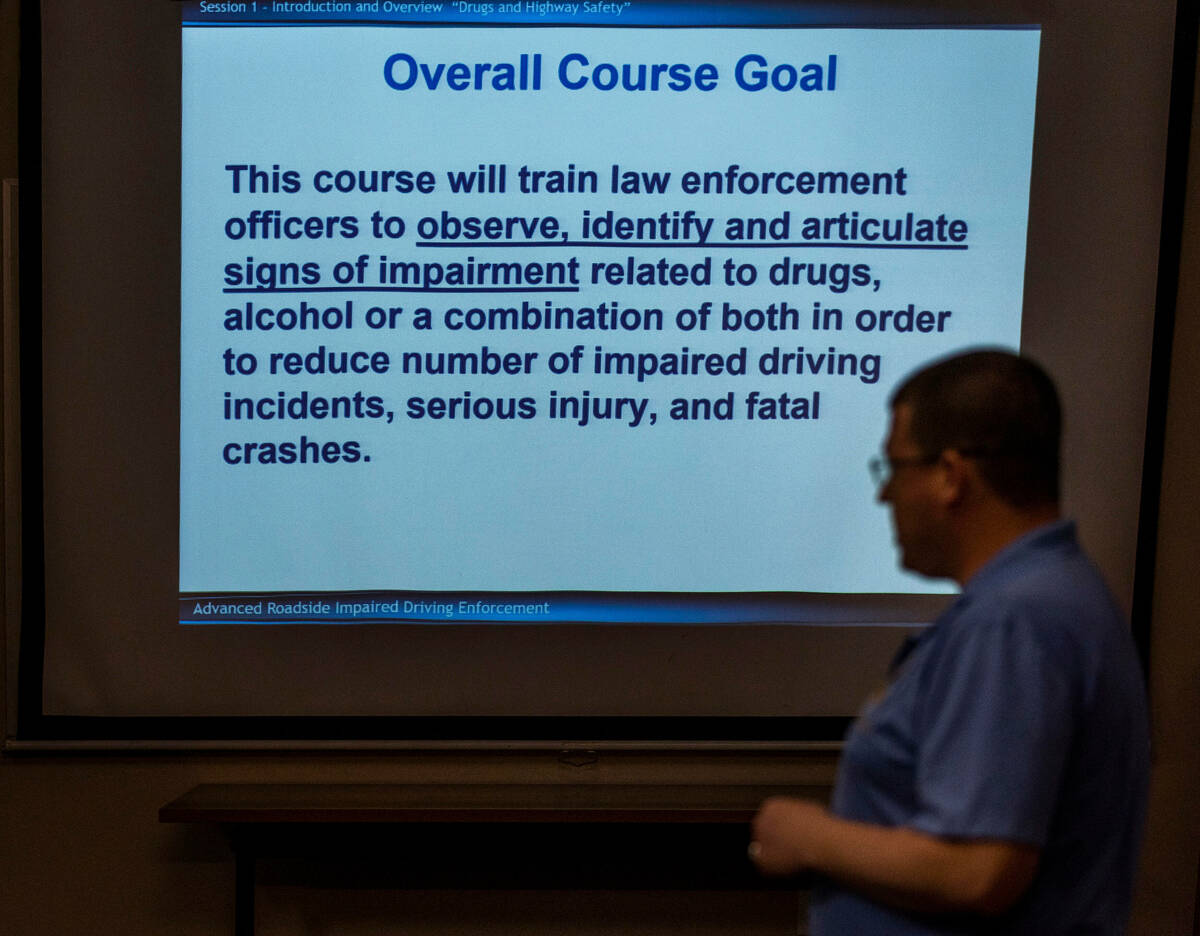

All of those factors make Advanced Roadside Impaired Driving Enforcement (ARIDE) training critical.

During February’s class at Metro’s traffic bureau on Cameron Street, officers were quizzed and instructed on the categories of drugs and how they affect the human body.

“If it doesn’t pass the common sense test, if the hair starts sticking up on the back of your neck, start asking more questions,” officer Rob Thiele told his students.

He and his brother, Mike, drilled officers on the cues and clues of marijuana use: body tremors, fast speech, short-term memory loss, inappropriate responses and reactions to light, such as pulsating eyes. Officers also noted medical conditions that could mimic those symptoms.

For some in the class, DUIs are personal. One patrol officer, Tom Rybacki, said his buddy’s father had been killed by a drunken driver.

“It could have been my dad,” he said.

Rob Thiele, who served 20 years in the Army, said he joined traffic enforcement, in part, because he has personally been affected by impaired driving.

“I didn’t lose soldiers in Afghanistan, but I lost five to DUIs after they came back,” he said.

In a matter of days, the training class would take to the streets to put what the students had learned into practice as part of a “DUI blitz.” Over Super Bowl weekend, the agency reported making hundreds of traffic stops and arresting dozens of people on DUI charges.

“At the end of the day, impaired is impaired,” Rob Thiele told the officers in class. “This puts more tools in your toolbox — so you can call B.S. on B.S.”

Contact Briana Erickson at berickson@reviewjournal.com or 702-387-5244. Follow @ByBrianaE on Twitter. Erickson is a member of the Review-Journal’s investigative team, focusing on reporting that holds leaders and agencies accountable and exposes wrongdoing.