Police help ICE seize undocumented immigrants jailed for nonviolent crimes

Las Vegas police help federal officials capture undocumented immigrants jailed for nonviolent crimes, a shift in practice that critics say was never made public.

The Metropolitan Police Department has also instructed jail officials not to record on inmates’ booking logs that they were picked up by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), Metro documents show.

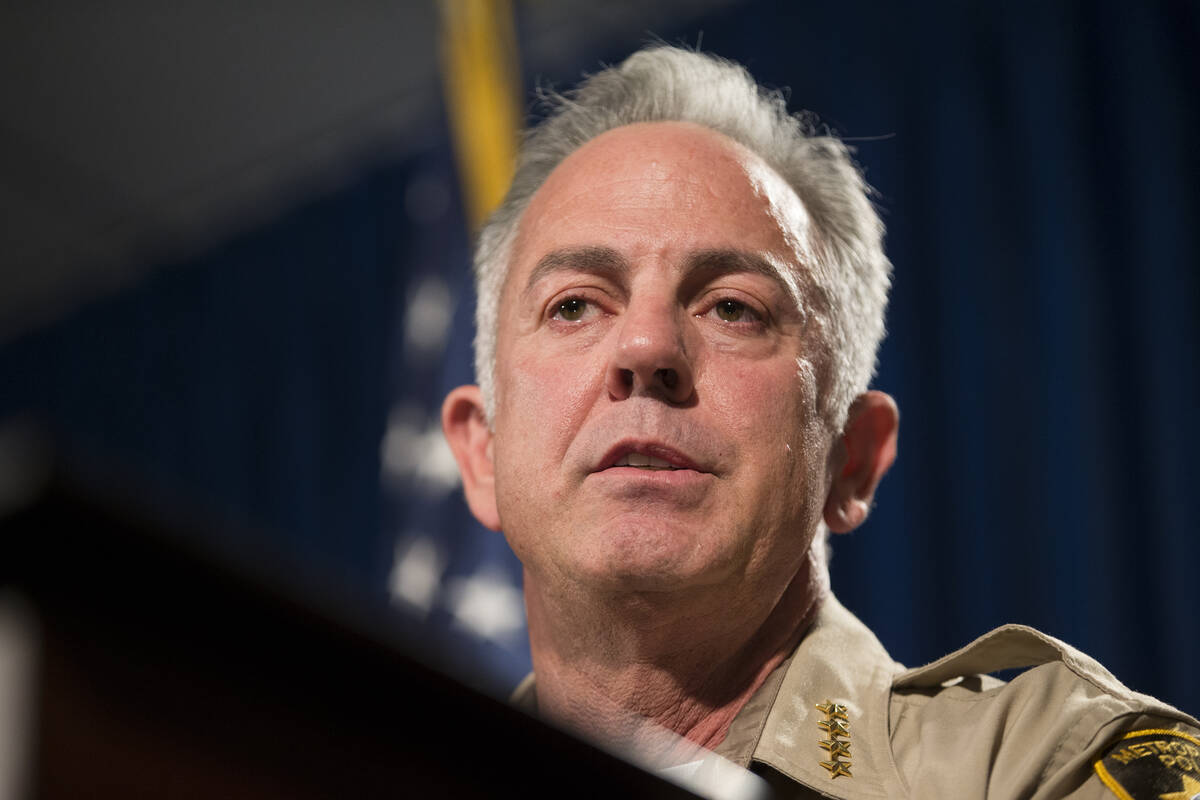

Illegal immigration is a top campaign issue for Republicans heading into competitive primaries in 2022, including Clark County Sheriff Joe Lombardo, who is running for governor. Many support deporting undocumented immigrants with any kind of criminal record, while Lombardo’s campaign promotes a “zero-tolerance policy for violent criminals.”

“When immigrants come to this country illegally and commit violent crimes in our communities, they need to be removed,” wrote the campaign in a statement, adding that the sheriff was “unequivocally pro-legal immigration.”

But local immigration advocates say Metro’s policy toward nonviolent offenders runs contrary to Lombardo’s public position. They also say the department’s record-keeping practice is nontransparent.

The Review-Journal obtained the policy through a public records request after Lombardo reportedly boasted at a July campaign event that he was involved in deporting 10,000 people. The policy change became effective one day after the sheriff announced in October 2019 that the county jail would exit the 287(g) program, its then-partnership with ICE.

Metro spokesman Aden OcampoGomez confirmed the practice while describing how the Clark County Detention Center helps ICE take inmates into federal custody.

“Whoever they’re interested in, we’ll give them a call,” he said.

The policy instructs jail staff to contact ICE “24/7” about inmates wanted for deportation proceedings, according to the document.

ICE agents are told when the inmate will be released from the jail so that they can be outside waiting to take them into custody, OcampoGomez said. The pickups are not recorded on inmates’ booking logs, a practice that diverges from record-keeping under the 287(g) program.

“In this case, we’re not transferring custody. We’re releasing this individual,” OcampoGomez said.

ICE has flagged more than 800 inmates since the current policy took effect, OcampoGomez said. Metro does not track how many inmates the federal agency takes into custody.

Some critics, including UNLV Immigration Clinic Director Michael Kagan, said the policy allows Nevada’s largest law enforcement agency to obscure its coordination with ICE.

“It’s not as if Metro is a passive actor here. They’re actively involved in the process and choosing to be actively involved,” said Kagan, whose clinic defends people facing deportation. “That means that they certainly have a responsibility to keep records to let the public know what they’re doing. That’s a basic requirement of transparency.”

But one national organization seeking to reduce overall immigration said it found the two agencies’ coordination acceptable.

“There’s nothing in the law that states you have to meet a certain threshold of crime to be remanded to ICE,” said Ira Mehlman, spokesman of Federation for American Immigration Reform in Washington, D.C. “We’ve seen countless examples in the past where a local police department has had someone in custody and released them when ICE asked them to hold them, and they went on to commit more crimes. That could have been totally avoided.”

Sen. Joe Hardy, R-Boulder City, said he believed such a policy helps keep undocumented immigrants wanted by ICE from eluding capture.

“There’s no motivation (for them) to stick around for a week and wait to be put in jail again,” he said. “I think we will always do better if we have cooperation between the state, the county and federal officials.”

ICE officials declined an interview, but regional agency spokeswoman Lori Haley wrote in a statement that its arrangements with local jails and police departments was crucial to taking undocumented immigrants into custody “in a safe and secure setting.” She added that the vast majority of people ICE takes into custody have criminal convictions or pending criminal charges.

Some members of the Clark County Commission, who determine the county jail’s annual budget, which is currently more than $250 million, said they were unaware Metro helps ICE apprehend inmates accused of nonviolent crimes.

“If they changed the policy internally I would hope they would let us know, because before we were clear that this was about violent crimes,” Commissioner Tick Segerblom said. “To the extent we can keep families intact is best for Las Vegas.”

Deportation data not available

City jails in the Las Vegas Valley also collaborate with ICE, but some report keeping more records than Metro about apprehended inmates.

The Las Vegas Detention Center reports more than 160 have been taken into custody since October 2019, when it also exited the 287(g) program.

The North Las Vegas Detention and Corrections facility could not provide the number of inmates handed over since the jail reopened in July 2020. However, individual inmates’ files do indicate if they were picked up by ICE, city spokesman Patrick Walker said.

Metro does not track how many county jail inmates ICE apprehends, OcampoGomez said. Emails from ICE notifying the jail about inmates of interest are also deleted after one year as a matter of department policy.

Local immigration attorney Dee Sull said when representing immigrants facing deportation, not knowing their chain of custody between law enforcement agencies can make it harder to determine if there was any wrongdoing in the process or subpoena an officer in the case of civil litigation.

After reviewing Metro’s policy, she added: “They’re removing themselves from being dragged into a lawsuit.”

Former 287(g) program

Under the now abandoned 287(g) program, Metro employees were deputized to act as immigration officers and alerted ICE of inmates wanted for deportation. The jail also honored ICE “detainers,” which allowed them to hold an inmate for 48 hours after their release date at the federal agency’s request.

Unlike today, a transfer of custody to ICE was recorded on inmates’ records because federal agents would schedule a pickup inside the jail, OcampoGomez said.

Metro suspended the 287(g) program after a federal district court ruled that ICE detainers could only be honored in states with laws that specifically address civil immigration arrests. However, police officials wrote in a statement they would “continue to work with ICE at the Clark County Detention Center in removing persons without legal status who have committed violent crimes.”

ICE contacted the jail about inmates at least 24 times since late October 2020, according to emails obtained by the Review-Journal. The correspondence does not state whether the inmate was taken into ICE custody.

Metro refused to release ICE documents in its possession to the Review-Journal that contain information about why the inmates were wanted for deportation, stating the federal agency must release them.

But the police department’s own records show at least five of those inmates were arrested for nonviolent crimes before ICE inquired about them. Generally they were charged with some combination of theft, drug and traffic violations, including driving under the influence.

Lombardo statement

Lombardo brought renewed scrutiny to Metro’s practices after the July campaign comment that he had helped deport 10,000 people, reported by The Nevada Independent. In September, his campaign’s Twitter account tweeted the sheriff “developed an internal system to identify and report illegal immigrants.”

Lombardo’s campaign website states that after he suspended the 287(g) program the sheriff “used extra personnel and dedicated scarce resources to working directly with ICE to determine the identity of violent criminals in other ways.”

ACLU of Nevada Executive Director Athar Haseebullah said he viewed Metro’s new policy as “a distinction without a difference” from the 287(g) program, outside of no longer holding inmates up to an extra 48 hours for ICE.

“They’ve found a workaround,” he said. “And even within that workaround, they don’t have to track any numbers, statistics or data.”

As Governor of Nevada I will ensure sanctuary cities are banned for the safety and wellbeing of all Nevadans! pic.twitter.com/zU7DPagr9l

— Joe Lombardo (@JoeLombardoNV) September 9, 2021

Lombardo’s campaign did not respond to repeated inquiries about the internal system or whether the sheriff had made the claim about helping deport 10,000 people. Metro spokesman Larry Hadfield said the department could not determine how many inmates were taken into custody under the 287(g) program because it no longer has access to ICE records.

One immigrant’s experience

An estimated 180,000 undocumented immigrants lived in the Las Vegas metro area as of 2016, according to the Pew Research Center. That was about 8.2 percent of the population, one of the highest rates in the United States and more than double the national average.

One inmate taken into ICE custody in early 2020 said that a federal agent was waiting inside the Clark County Detention Center to handcuff him when he was released.

“Basically the (jail) officer just handed me to him,” said the undocumented immigrant, an El Salvadorian man represented by Sull, the immigration attorney.

The Review-Journal granted the man and his girlfriend anonymity because they fear retaliation. He is still litigating his deportation case.

The man said he was arrested while he was driving on an errand with his daughter. A Metro officer pulled him for talking on his cellphone while driving, according to his arrest report.

Metro arrested the man on multiple charges, including DUI and child neglect. Prosecutors declined to formally charge him with either of those two charges, and he was later found guilty of driving without a license, court records show.

After his girlfriend posted his bail overnight, the man said an ICE agent handcuffed him inside the jail as soon as he finished his paperwork to leave the facility. His girlfriend said she spent hours trying to figure out why he didn’t come home, but her calls to the jail were fruitless.

“Everyone said, ‘No, we’re sure he’s out,’ ” she recalled. “It was very frustrating. I was scared something happened to him.”

He had previously been deported after being convicted of a felony drug charge, records show. He said he returned to the U.S. because of gang violence in El Salvador, his original reason for leaving his home country as a teen.

Once ICE apprehended him in early 2020, the immigrant said he spent six months at the Nevada Southern Detention Center in Pahrump, about an hour’s drive outside of Las Vegas. Due to COVID-19 restrictions, he was mostly unable to see his family.

The man was released on bond a few months later and is appealing his immigration case. He said he’s working two jobs to make up for the income he lost while locked up, and he must report to ICE on a weekly basis.

“You’re living day by day,” he said of the situation. “You never know if they’re just going to show up at my house and take me again.”

While ICE typically apprehends undocumented immigrant inmates as they exit the jail, there is no rule forbidding agents from taking them into custody inside the jail, said Hadfield, the Metro spokesman.

“If they are there and the inmate is being released, they can take them into custody,” he said.

While the man’s reasons for leaving El Salvador sound understandable, Sen. Hardy said immigration officials likely could not ignore his previous criminal conviction and deportation.

“I think ICE would have a hard time saying that’s a person we want to give leeway to,” he said.

The Associated Press contributed to this report.

LVMPD immigration jail policy by Las Vegas Review-Journal

Contact Michael Scott Davidson at sdavidson@reviewjournal.com or 702-477-3861. Follow @davidsonlvrj on Twitter.

National policy

President Joe Biden in February ordered ICE to focus on apprehending undocumented immigrants who committed "aggravated" felonies, the Associated Press reported. A federal judge blocked that order in August, but new, similar guidelines targeting those accused of "serious criminal activity" will go into effect Nov. 29.

The Washington Post reported last month that ICE officers made about 72,000 administrative arrests during the most recent fiscal year, according to unpublished agency data obtained by the newspaper. The agency made about 104,000 arrests during the 2020 fiscal year, and it averaged about 148,000 arrests per year from 2017 through 2019.