Selling dead people’s homes lucrative for some. But what about the heirs?

After Essie Walker died in the summer of 2019, it wasn’t long before someone staked a claim on her house.

Thomas G. Moore, a man with no ties to the family, filed court papers to take control of Walker’s estate six months after the 84-year-old woman’s death.

He later sold her home in Las Vegas’ Historic Westside, and the one-story, 1960s-era property proved a big money-maker. Walker’s probate case generated more than $20,000 in legal fees, real estate commissions and administrator fees — and the home buyer, who helped cover those costs, flipped the renovated house within months for more than $90,000 above his purchase price, records show.

Walker’s son, Robert Lee, recalled he was told he might get some money through the case, and he got on board with Moore’s efforts a few weeks after the outsider sought court authority to manage his mom’s estate.

But Moore’s lender-approved sale left no money for the family, court records show, and Lee and his wife, Veronica Gisendaner, confirmed they didn’t receive a dime.

When told about the fees people earned, Gisendaner said, “We feel like we got screwed.”

Clark County probate court has for years been a lucrative arena to profit off the dead. A cottage industry of private administrators, real estate agents, lawyers and house flippers reaped hefty paydays selling homes across Southern Nevada after the owners died. The probate cases routinely started without family participation and often ended with nothing for heirs, a Las Vegas Review-Journal investigation found.

Under Nevada law, virtually anyone can swoop in to sell a dead person’s house with limited court oversight. Two prolific private administrators — Moore, founder of Estate Administration Services, and his probate successor, real estate agent Cynthia “Cyndi” Sauerland of Compass Realty & Management — were involved with at least 500 probate cases combined in Clark County over the last several years.

In nearly 400 of those cases, they initially stated they couldn’t identify or communicate with heirs. They also obtained court authority more than 460 times to sell homes through a process that doesn’t require court approval of the deal or competitive bidding that could boost the sales price, an analysis of District Court records dating to 2016 shows.

Moreover, the duo frequently sold homes at steep discounts to estimated values — often to the same circle of investors who resold the properties within months.

Their three biggest buyers flipped more than 130 homes for $13.4 million above the combined purchase price, the newspaper’s nine-month investigation found.

Moore, who is 41 and now lives in Washington state, generated more than $900,000 for heirs across roughly 30 cases in Southern Nevada, court records show. But in at least 285 cases, he indicated in court filings that he was unable to recover any money for heirs, often because he sold homes for less than what was owed on the dead owner’s mortgage in lender-approved “short sales.” Other times the homes went into foreclosure.

Still, his casework paid out more than $2 million in real estate commissions, over $1.2 million in legal fees and more than $300,000 in administrator fees.

His cases also generated hundreds of thousands of dollars for services with vague descriptions in court records that some Southern Nevada probate lawyers, and a few real estate agents with short-sale experience, had never heard of, the Review-Journal found.

Casework

Thomas Moore of Estate Administration Services and his probate-work successor, Cynthia Sauerland of Compass Realty & Management, collectively managed hundreds of probate cases in Clark County District Court.

Here are ten of them.

‘A service to the community’

Moore, Sauerland and their associate Adam Fenn of Compass — who bought at least two dozen homes through probate from Sauerland and flipped most of them — contend they are helping solve the problem of abandoned houses.

Empty buildings in Southern Nevada are prone to being taken over by squatters, falling into disrepair and even going up in flames. Many of the homes sold through probate were abandoned, at risk of foreclosure and dilapidated, the group said.

In one case, Sauerland sold a house through probate to Compass owner Takumba Britt after local officials deemed it unsafe to occupy.

“It’s a service to the community,” Sauerland said. “It’s not just, ‘Everybody’s running around making money.’”

Fenn said that many heirs had washed their hands of the situation and that his group helps neighbors who live near problem homes. He declined to say how they find properties left by the dead.

“This is something we feel we’re the solution for,” he said.

Still, the administrators have faced some sharp criticism.

At a court hearing in 2020, a lawyer for a family that sued Moore in a now-settled case called him a “predator” who “tries to take properties away from families” — a claim Moore’s legal team strongly disputed, a court transcript shows.

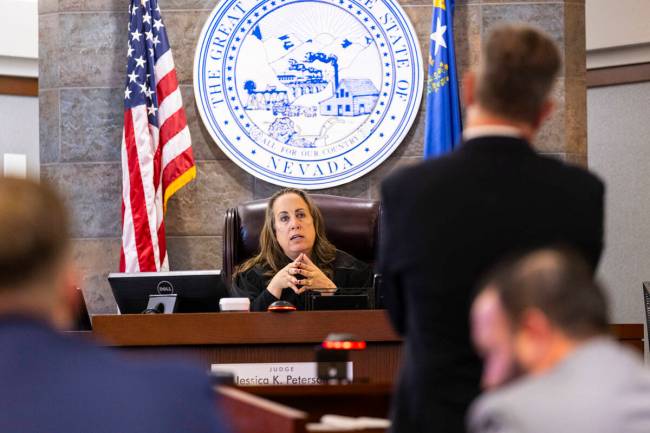

In 2022, District Judge Jessica Peterson said in court that she had a “real problem” with whether Sauerland was telling heirs about any fees the administrator or her lawyer would take.

Peterson also criticized the $8,500 payment that Sauerland’s legal counsel earned in the case and ordered her lawyer to furnish invoices. The judge later wrote that further investigation was needed to see if Compass should forfeit its commissions.

The Clark County public administrator’s office says it manages estates in court when families cannot. Former Public Administrator Robert Telles, for one, was a frequent critic of Moore and Sauerland and tried to block their attempts to land cases, court records show.

“We were his punching bag every week,” Fenn said.

Telles told Nevada lawmakers in 2021 that there were some probate cases where equity that might have gone to family members and others was “washed away” by third parties, whom he did not name.

This “may not be illegal,” but families need to be protected, he told the Senate Judiciary Committee.

The next year, Peterson tasked Telles with running the inquiry into the fees. But not long after, Telles was arrested on allegations that he murdered Review-Journal investigative reporter Jeff German, who had written about Telles’ divisive tenure in office.

He has been jailed ever since.

‘This is not acceptable’

Probate cases involve transferring ownership of a dead person’s property through court and settling debts. It can be avoided, including by shifting property to a trust or drawing up a deed that transfers real estate upon death, according to an article by Las Vegas probate lawyer Laura Deeter.

Leaving a will doesn’t guarantee that probate can be dodged in Nevada. A will typically outlines who gets what after a person dies, but probate would still be needed to distribute assets that don’t automatically transfer, according to probate attorney Jeffrey Burr’s law firm.

If probate is required, state law provides a 10-deep list of who can manage the estate that begins with family and ends with anyone “legally qualified” for the task.

It’s a low bar. Any adult in Nevada can run a probate case if the person is not a convicted felon. Would-be administrators could also be blocked over a conflict of interest, “drunkenness” and “lack of integrity,” state law says.

Court officials were aware of “concerns and trends” in probate cases and, in response, imposed heightened scrutiny on third-party administrators in early 2023, said District Court spokeswoman Mary Ann Price.

The administrators were required to detail in writing how they looked for relatives and documents, and, when pursuing the independent route that Moore and Sauerland relied on, to co-manage cases with an heir or family member.

Since the increased scrutiny kicked in, there have been fewer requests for independent administration, according to Price.

But just a few months ago, Judge Peterson pointed to other problems in the system, vowing to find cases that were never closed out.

“This is not acceptable,” she said at a hearing in October. “People are taking administrator fees, and people are getting attorneys’ fees, and not doing anything to protect people.”

‘This isn’t a scheme’

When a person dies, usually a relative submits court papers to start a probate case, according to the State Bar of Nevada.

Sauerland, however, works with investors who scope out properties and approach her and her legal team to open probate cases and obtain court authority to sell the homes, her attorney Christopher Wood once said in court.

Many homes tracked for this report were renovated, listing sites show, and Sauerland said she gets unsolicited emails from people thanking her for her work. She provided the Review-Journal with several emails praising her efforts.

“This is what it all breaks down to: Helping the community and helping heirs — you know, of course, if you can find them,” she said.

Fenn insisted that other people don’t handle or understand short sales and that his team works complex situations.

“This isn’t a scheme,” he said. “We’ve been doing this for a long time.”

Under Nevada law, almost any adult resident can administer a dead person’s estate and sell their home through probate court if a family member does not step forward.

To evaluate the impact of this practice, the Las Vegas Review-Journal tracked the outcomes of hundreds of probate cases handled by Thomas G. Moore and his probate-work successor, real estate agent Cynthia “Cyndi” Sauerland.

The newspaper obtained a public database of probate cases from Clark County District Court that showed Moore and Sauerland were two of Southern Nevada’s most prolific private administrators in the past decade. Two reporters inspected court filings in approximately 500 cases that either Moore or Sauerland were involved with from 2016 to 2023.

More than 350 home sales by Moore and Sauerland were analyzed to determine whether the properties were sold for more or less than the estimated values that the two administrators provided in court filings, which were typically drawn from listing sites such as Zillow or Redfin.

Reporters read through title-company settlement statements filed in court to determine the fees and commissions paid through the cases, as well as attorney invoices that were enclosed in court papers.

The newspaper also tracked who bought the homes from Moore or Sauerland, whether these buyers resold the homes, how quickly they did this, and how their sales price compared to their purchase price.

Additionally, the Review-Journal spoke with heirs to estates that Moore and Sauerland were involved with, and spoke with real estate agents, probate lawyers and other industry experts.

An administrator’s job is to preserve money, pay bills and distribute what’s left to the heirs, said John Midgett, president of the National Association of Estate Planners and Councils. He also noted that state laws governing who can run probate cases vary across the country.

Minnesota, for one, doesn’t have a “catch-all” provision like Nevada that lets virtually anyone manage a case, according to Julian Zebot, chair of the trust and estate litigation group at Minneapolis law firm Maslon LLP.

Zebot said he wasn’t aware of anyone in the Twin Cities area who looked for probate cases to open and then sold homes to flippers. “It sounds very opportunistic,” he said.

Henderson attorney Elyse Tyrell, who has roughly three decades of probate experience in Southern Nevada, said she had never seen administrators who were complete strangers to families open cases until Moore and Sauerland came along.

Tracking down family could be hard, Tyrell said. But as she sees it, administrators shouldn’t be able to interject themselves in strangers’ estates, and there’s only one reason to do it: to make money.

“I can’t imagine any other motive,” Tyrell said.

‘Similar to the payday loan business’

At the court hearing where an attorney called Moore a predator, Moore’s lawyer Patrick Chapin disputed that his client did anything unlawful.

In that case, Moore had obtained court authority in 2019 to administer the estate of Tsoghik Khachatryan, who died in 2013 at age 30 of a suspected aneurysm.

Her husband, their kids and other relatives stayed in the southwest Las Vegas house she owned, but they were forced out after Moore landed control of Khachatryan’s estate, according to court filings by her husband.

When the husband sought to manage the estate himself, Moore quickly resigned from the probate case, court records show. The family later sued Moore and others, alleging they wanted to gain possession of the house to “enrich themselves.”

In the lawsuit, the family claimed they were forced to sleep at the restaurant they owned but were allowed back in the home about 10 days after the eviction.

Chapin noted in court that his client had obtained court approval to oversee the estate. There was no evidence to call anyone vultures or predators, he said.

“It may be a distasteful business for some people. They may not like it — it’s similar to the payday loan business — but it is the law that was followed here,” Chapin said.

The case was settled and then dismissed in 2021, court records show.

Moore and the Khachatryan family’s attorney Michael McNerny declined to comment on the case.

Family not found

On many occasions, family members nominated Moore or Sauerland to run their relatives’ probate cases. But the duo routinely initiated court proceedings without heirs.

In roughly 80 percent of his initial petitions to oversee cases, Moore did not identify any known heirs or he named them but stated he could not communicate with them, the Review-Journal found. For Sauerland, that figure was around 73 percent.

Fenn said that figuring out where people live isn’t hard and that his team has field-services personnel who knock on doors. But actually talking with them is another issue, he noted.

“We’re not in the business of harassing someone, like calling them 85 times saying, ‘We’re trying to clean up the mess here,’” he said.

Family members often lived locally. In more than 100 cases where Moore and Sauerland initially claimed they could not communicate with heirs, the relatives’ listed address was in the Las Vegas Valley, and in dozens of those cases, it was the same as the dead homeowner’s, court filings show.

In one case, Moore filed court papers to oversee Eddie Buford’s estate two years after she died at age 81. Neva Buford was listed on the death certificate as the informing party and had the same North Las Vegas address.

Moore initially wrote their relationship was “unknown.” Turns out Neva was Eddie’s daughter.

“This person was listed on the death certificate at the very address in which they’re saying, ‘Oh, we don’t know anything about it,’” then-Probate Commissioner Wesley Yamashita said in court in early 2020.

Moore told the Review-Journal that he oversees a research and sales department to get in touch with heirs, that every situation is different, and that there is “no carbon copy answer as to how I get in touch with someone and what the timeframe is.”

Neva Buford told the Review-Journal that she had moved in with her mom years earlier to care for her and was with her the morning she died.

At first, Neva Buford figured that she’d keep the home in the family. She later signed a document nominating Moore to run her mom’s probate case two months after he sought court authority, records show.

He sold the house to frequent buyer Gary M. Wilson in a short sale that left no assets for heirs, according to court records. Compass earned commissions in the case.

Wilson flipped the house several months later for almost $115,000 above his purchase price. A listing on Zillow shows new countertops, flooring and other upgrades.

Neva Buford said she received more than $1,000 from Compass to help with moving costs.

She grew up in the house and didn’t know it had been flipped until the Review-Journal told her, saying it made her feel sick.

‘They were entrepreneurial’

Fenn said his team helps neighborhoods by selling homes that can become a mess after the owners die.

“You’re never going to hear one neighbor scrutinize anything we do because we’re doing something so good for them,” he said.

When Sidney Vengrow died at age 81, the former casino dealer left a condo in Henderson that was later found to have an overflowing kitchen sink and widespread mold, soaking-wet carpets and algae growth, court records show.

Moore sold the unit in 2019 for $52,250 to frequent probate buyer Wilson, who flipped it less than a year later for $170,000. A listing on Zillow shows the condo was fully remodeled.

Steven Vengrow, the former owner’s nephew, said his uncle didn’t have any kids and that when he was first contacted about the probate case, it sounded fishy. He noted the condo was upside-down on its mortgage.

Vengrow said he didn’t get any money from the sale, but he harbors no hard feelings.

“I give them credit,” he said. “They were entrepreneurial.”

Not everyone offered that outlook. Interior designer Susan Heath, who gained control of her mom’s estate after Sauerland took charge, told the Review-Journal the whole experience was bizarre.

Her mom, Helen Meyerson, died at age 96 in 2020. When Sauerland sought court authority the next year to oversee the estate, she wrote that she was unable to communicate with any heirs.

According to a subsequent court filing, Sauerland had been in contact with Heath, who indicated she did not want to manage the case.

District Judge Gloria Sturman put Sauerland in charge. But a week later, Heath’s attorney filed court papers saying his client did not want Sauerland overseeing the case.

The judge later removed Sauerland and named Heath the administrator.

“I didn’t know Cynthia-whatever from a hole in the ground,” Heath said.

Heath sold her mom’s house in Summerlin this past November for $415,000, property records show. She expects to receive some money through the case, but not much, she said.

Still, she’s glad she took charge of the estate. “It was pretty weird the other way,” she said.

‘Make probate a breeze!’

Moore’s firm specializes in distressed properties and is often able to recover assets for heirs, according to its website.

More often than not, court records show, heirs didn’t get any money from his probate sales.

He claimed or indicated in more than 90 percent of nearly 350 petitions for cases that the homes were or could be underwater, meaning the mortgage debt exceeded the property value. He ultimately reported some 160 short sales that generated no proceeds for heirs, court records indicate.

Moore — whose company’s mailing address is the same as Compass’ office in southwest Las Vegas — said in court papers that he “passed the torch” for his probate work in 2020 to his “former colleague” Sauerland.

Her website touts compassionate oversight of cases and promises to “make probate a breeze!”

The Review-Journal was unable to tally how much money heirs received from her casework, largely because Sauerland’s court filings often did not say how much went to them.

Still, Sauerland initially said the estates had a net value of approximately $0 in more than 40 percent of her petitions tracked by the Review-Journal.

When asked how much money heirs received through their cases, Moore and Sauerland both referred to their legal counsel.

Clear Counsel Law Group, which represented Moore in almost all of his cases, and Wood, Sauerland’s attorney in 150-plus cases, did not comment.

‘You don’t just put this on the market’

Moore and Sauerland’s probate sales were often followed by quick flips.

Wilson, of GMW LLC, purchased at least 67 homes from Moore and resold all but three within a year. His median purchase price from Moore was $150,000, while his median flip price was over $240,000, property records show.

Another frequent buyer, Avi Segal, flipped nearly 40 homes he purchased from Moore. His median flip price, $249,000, was more than $100,000 above his median purchase price.

Moore even sold one house through probate to an entity called We Flip It LLC, which, true to its name, sold it less than a week later for almost $30,000 above its purchase price.

“If they’re all being flipped, clearly they’re … not all dead ends,” said Tyrell, the lawyer.

Sauerland noted that buyers might have to spend a fortune to renovate these homes.

“So really, what is the profit margin for the flipper?” she said. “Probably not double.”

Wilson and Segal could not be reached for comment.

Fenn said a typical buyer might have to jump through numerous hoops to purchase a home, and if they can’t close the deal, both sides will have wasted time. But when he buys the home, the process is “extremely efficient.”

He acknowledged that listing a typical sale could draw more buyers and boost the price but added that his probate work doesn’t deal with regular real estate.

“It’s in insurmountable distress,” he said. “That’s kind of what we’re solving here. You just don’t put this on the market.”

Las Vegas Review-Journal

Selling dead people’s homes can be a lucrative business in Las Vegas — even though families of the deceased might get nothing.

Clark County’s most prolific private administrator on record for the past decade, Thomas G. Moore, sold 230-plus homes through probate court. But on at least 164 occasions, he reported having nothing to distribute to heirs because he sold the home for less than what was owed on the mortgage in a lender-approved short sale, a Las Vegas Review-Journal investigation found.

Still, his cases generated at least $2.9 million in legal fees, real estate commissions and other payments, including some reimbursements, from the sales proceeds, according to an analysis of District Court records.

His casework also produced payments for services that, as listed in court filings, were a mystery to some probate lawyers and real estate agents with short-sale experience.

Moore, who is 41 and now lives in Washington state, said in an email that short sales are subject to an “extreme” approval and audit process with lenders and insurers.

“It’s a very regulated transaction,” he said.

Money-making deals

Moore, founder of Estate Administration Services, and his probate successor, real estate agent Cynthia “Cyndi” Sauerland of Compass Realty & Management, administered hundreds of probate cases combined in District Court in the past several years.

They often started the cases without family involvement and obtained authority to sell homes through a process that doesn’t require court approval of the deal or competitive bidding. They also frequently sold to a small circle of repeat buyers who flipped the properties, the Review-Journal found.

Moore, Sauerland and their associate Adam Fenn of Compass Realty contend they are finding buyers for abandoned houses that can be taken over by squatters, fall into disrepair and become a neighborhood nuisance.

Moore, for one, told the Review-Journal that he sold “some of the most dilapidated, condemned, and fire-damaged houses you have ever seen.”

People who worked on his cases also made plenty of money.

Clear Counsel Law Group, which represented Moore in almost all of his cases tracked for this story, earned at least $1.16 million working with him, the Review-Journal found.

The firm declined to comment.

Compass booked almost $890,000 in commissions across nearly 120 of Moore’s cases, though it also paid for more than $135,000 worth of legal fees and other bills.

Fenn’s former brokerage, Haines & Krieger Realty, earned more than $600,000 in commissions across nearly 100 of Moore’s cases.

Also, “EAS” — which Fenn confirmed was Moore’s company — collected more than $310,000 in administrator fees through dozens of cases. Most of that money came from the buyer’s side in the transactions, court records show.

Fenn pointed to the costs and work involved with running probate cases and said the business isn’t as profitable as people might think.

It’s not like “everyone is swimming in money,” he said. “It’s not even close.”

‘Abatement’ fees

After Louise Williams died at age 87 following a stroke, Moore sold her southwest Las Vegas house for $150,000 to frequent probate buyer-and-flipper Avi Segal.

The short sale left no money for Williams’ adult son, but real estate commissions totaled $9,000, the law firm that worked the case with Moore made $5,000 and EAS’ administrator fee topped $9,400, with the latter two fees paid by the buyer, court records show.

Two fees paid by the buyer had vague descriptions.

An entity named “RTS” earned more than $7,000 for “foreclosure monitoring,” and “LV Abatement Services” booked more than $16,000 for “abatement services,” court records show.

Fenn confirmed that RTS is his entity Rapid Trustee Sale Inc. and that, as county records show, he also owns LV Abatement Services.

Overall, Moore’s cases paid out more than $900,000 to private entities — including Fenn’s — for costs listed in court records as foreclosure monitoring, abatement services, abatement fees or just “abatement.” Those funds were mostly paid by the buyers in the transactions.

The biggest recipient in that group — usually listed as just LVHS — took home around $700,000 in abatement-related charges, court records indicate.

Fenn confirmed this entity is controlled by frequent probate buyer-and-flipper Gary M. Wilson, whose businesses have included LV Home Source LLC, state records show.

Wilson could not be reached for comment.

‘They must know something I don’t’

Southern Nevada probate attorneys Elyse Tyrell, Bob Morris and Kennedy “Kenny” Lee — who work for separate firms — said they had never heard of foreclosure-monitoring or abatement-services fees.

Realty One Group branch manager Tim Kelly Kiernan, who said he handled more than 100 short sales a decade or so ago after the mid-2000s housing bubble burst, also hadn’t heard of those fees.

Neither had Tom Blanchard, managing broker with Signature Real Estate Group, who said he’s handled nearly 1,000 short sales in his decades-long career.

Finding cases

Adam Fenn of Compass Realty & Management declined to say how his team finds homes left by the dead that can be used for probate cases in District Court.

During an interview, he said multiple times that his team had trade secrets.

In theory, they could scan obituaries and then see if the deceased owned a home. They could also track publicly available filings with Clark County that might stem from a homeowner’s missed payments — including liens and default notices — and then try to find out if the owner was still alive.

Locally, death certificates are confidential and only released to qualified applicants, said Southern Nevada Health District spokeswoman Jennifer Sizemore.

This includes people who filed a petition in probate court, as it meets the district’s requirement to facilitate a legal process, she said.

When an applicant has no apparent relationship to the deceased or the dead person’s family, the health district requires proof that a petition was filed before it releases the records, she added.

— Eli Segall

Fenn said foreclosure-monitoring work includes postponing foreclosure sales, and he estimated his team defers more than 100 such auctions per year.

He also said that his LV Abatement entity charges fees for short-sale negotiation and management and that his team handles cases at no cost to heirs.

“I know it might look high, but it’s really not that high to go through a year-long legal process and do what most people can’t, which is short-sale negotiations for these types of houses,” he said.

Lee noted he’s not an expert on all of the closing costs. But he also said his law firm isn’t interested in taking a case if it appears the sole asset is a house that would be subject to a short sale.

There’s no guarantee a lender will even approve the deal. Plus, there’s already a way to deal with financially distressed properties, Lee said: The bank can foreclose on the house.

Morris also said he’s not interested in cases with short sales, and that he’d rather let the bank foreclose.

“They must know something I don’t,” said Morris, who has nearly two decades of probate experience in Southern Nevada.

No bids required

Lenders try to sell the homes they foreclose on. According to Fenn, however, attorneys who advise clients to walk away from such properties are “unknowingly” contributing to the problem of abandoned houses.

He said his team can get attorney’s fees paid through short sales so the lawyers can work the case and “hopefully discover something beneficial to the estate.”

Underwater homeowners who are still alive wouldn’t get a dime from a short sale, either. Their lender is taking a loss on the deal, and the seller’s “payment” is being able to walk away from the house without having to make up the bank’s shortfall.

Tyrell, however, said the high volume of underwater homes and short sales tracked by the Review-Journal raised concerns for her, noting that an administrator could still get paid even if the family doesn’t.

“I’m always concerned when there’s nothing for (the) family and nothing for heirs,” she said.

According to Fenn, heirs understand the house is underwater, and they usually just don’t want to owe anything to anyone.

While Moore routinely sold homes for less than what was owed on the mortgage, he also wasn’t required in the vast majority of his cases to take bids that might boost the sales price.

He obtained court authority for “independent administration” in at least 340 cases, or nearly every time he requested it, the Review-Journal found.

Sauerland told the Review-Journal that 65 percent of her sales had equity for the estate. She obtained independent administration authority at least 125 times among 150-plus requests, court records show.

This provision of state law lets an administrator sell real estate without a judge’s approval or competitive bidding through court, attorneys said.

It’s a useful tool when heirs agree on what to do with a home, as they can sell it faster through court, attorneys said.

Moore said his legal counsel recommended using this provision of the law because of the issues with abandoned real estate, adding it was best to move quickly because of the mounting debt and rundown conditions.

Sauerland said that squatters can get inside these homes and the sooner the properties are dealt with the better.

“It’s a quicker process, but that’s not to mean that we’re trying to race to the end and just make a bunch of money and run away,” she said.

‘It doesn’t make sense’

The Review-Journal tallied payments in Moore’s cases by analyzing title-company settlement statements filed in court that disclosed fees, commissions and other transactional costs in cases he worked.

He said in court papers that he passed the torch for his probate work to Sauerland in 2020. The newspaper tracked more than 150 cases that Sauerland initiated through March 2023, but reporters were unable to determine whether her casework included all of the same kinds of payouts as her predecessor.

Sauerland’s court filings sometimes included attorneys’ invoices, but there were no settlement statements in virtually every case.

When asked about the differences in filings, Sauerland referred to her attorney Christopher Wood, saying he had all the paperwork.

Another difference between her and Moore: Sauerland said she doesn’t take administrator fees.

Wood said at a court hearing in 2022 that his client does not take a personal-representative fee or a sales commission in her cases. He also said that she works with investors who are eyeing the properties and that she’s an hourly employee.

Wood did not comment when contacted by the Review-Journal.

‘The family got nothing’

After Redjep Abdul died from cancer at age 85 in late 2020, his daughter Debbie Erbach was stunned and confused as strangers took control of his Henderson house.

In his will, Abdul had named Erbach his personal representative and gave her authority to sell or otherwise deal with any property that belonged to his estate, court records show.

Then in April 2021, Sauerland sought court authority to administer Abdul’s estate. District Judge Jessica Peterson put her in charge of his probate case that June, and Sauerland sold his house through the case that September, records show.

Clark County’s then-Public Administrator Robert Telles, however, filed court papers in March 2022 to take over the case, saying Erbach had nominated him for the task.

As outlined in a title-company statement Telles enclosed in his court filing, Compass was to receive more than $14,000 in commissions from the sale. Sauerland failed to disclose to the court her “financial interest” in the transaction when she sought the case, Telles wrote.

Wood’s firm, Wood Law Group, earned $8,500, according to the financial statement. But neither Sauerland nor her attorney had petitioned the court to approve the payment, Telles wrote.

The statement also showed that “RTS” fetched more than $3,000 for foreclosure monitoring and property maintenance, added Telles, who couldn’t determine anything about the company.

He also wrote that, according to Erbach, there had been “no attempt” to close out the estate and pay the heirs.

Wood replied in court papers in June 2022 that Erbach had not voiced any objections to the sale and that his client believed the estate was ready to distribute funds to heirs.

There was more than $16,000 in assets on hand, according to Wood’s court filing, which did not explicitly say how much money Abdul’s family would receive.

At a court hearing that month, Erbach said — under oath — that after she received notification of the case, she spoke with Wood. He told her not to worry about it, that his group would sell the house and that any proceeds left would go to the family, she recalled.

Erbach also said the sale notification showed fees and commissions, including to the real estate firm where Sauerland worked.

“At no time was it explained to us … exactly what they do and how this process works,” Erbach told the court.

Judge Peterson said in court that Wood’s payment in the case appeared “unacceptable,” and she wanted invoices to support it.

She signed an order Aug. 31, 2022, that put Telles in charge of the probate case and sought further investigation to see if Compass should turn over its commissions.

Within days, however, Review-Journal investigative reporter Jeff German was stabbed to death outside his house, and Telles was soon in jail, charged with killing him in retaliation for stories German wrote.

Erbach told the Review-Journal that she and her siblings still haven’t received a dollar from the sale.

“Everybody else got their money,” she said, “but the family got nothing.”

Las Vegas Review-Journal

Nevada attorneys made big promises when they pushed for a change to probate law more than a decade ago.

The proposed new way to sell dead people’s homes and settle their finances would speed up cases, reduce burdens on the court and slash costs, they said.

All told, case administrators could act more independently, as court supervision was in many cases “neither helpful nor necessary,” proponents told lawmakers.

Since then, two prolific administrators used the legal provision hundreds of times combined in Southern Nevada. They also routinely started those cases without family participation, often generated no sales proceeds for heirs and frequently sold homes to a small circle of buyers who flipped the properties, a Las Vegas Review-Journal investigation found.

Probate cases involve transferring ownership of a dead person’s property through court and settling debts. Under the “independent administration” option Nevada lawmakers adopted in 2011, a house can be sold without a judge’s approval or competitive bidding through court, probate attorneys said.

It’s a useful tool when family members agree on what to do with property a dead relative left behind, according to attorneys. Heirs can sell the home faster through court and move on with their lives.

But by design, this route through probate court provides less oversight of the sale and no court-supervised bidding process that might push up the price.

“There’s no accountability,” said Donnalyn VanOrman-Wasano, a private fiduciary in Henderson who works with trusts and estates.

State Sen. Melanie Scheible, D-Las Vegas, chair of the Senate Judiciary Committee in the last two regular legislative sessions, said Monday she found it troubling that people were profiting from the deaths of individuals whose families did not take over the estates.

It’s too early to say whether any laws need to be changed, said Scheible, who believed the issue “definitely deserves” some attention from Nevada legislators.

“It kind of sounds like there’s a loophole here,” she told the Review-Journal.

Assemblywoman Brittney Miller, D-Las Vegas, chair of the Assembly Judiciary Committee in last year’s session, did not respond to requests for comment.

Frequent court approval

Court officials were aware of “concerns and trends” in probate cases and, in response, imposed greater scrutiny on third-party administrators early last year, District Court spokeswoman Mary Ann Price said.

There have since been fewer requests for independent administration, she said.

Two of Southern Nevada’s most prolific private administrators of the past decade, Thomas G. Moore and his probate successor Cynthia “Cyndi” Sauerland, were involved with at least 500 probate cases combined in District Court over the last several years.

They also sought independent administration virtually every time, and the court routinely granted it.

Many of their cases started without family on board. In roughly 80 percent of his initial petitions to oversee cases, Moore did not identify any known heirs or he named them but stated he could not communicate with them, the Review-Journal found. For Sauerland, that figure was around 73 percent.

Moore, founder of Estate Administration Services, obtained court authority for independent administration in at least 340 cases among 345 requests tracked by the Review-Journal.

Sauerland, an agent with Compass Realty & Management, secured this authority at least 125 times among 153 requests, court records show.

Ultimately, the duo sold at least around 360 homes through probate court, and their three biggest buyers alone flipped more than 130 homes for $13.4 million above the combined purchase price, the Review-Journal found.

Las Vegas probate lawyer Kennedy “Kenny” Lee said independent administration, in general, offers more control over who buys the home. The family might want to sell to a friend, for instance, even if that person can’t pay top dollar, he said.

But selling with court confirmation allows for a bidding process, and depending on market conditions, buyers might push up the price, he said.

‘It’s a quicker process’

Under Nevada law, almost anyone can manage a probate case. Family members have top priority, but last on the 10-deep list in state law is anyone “legally qualified” for the task.

It’s a low bar, as any adult in Nevada can run a probate case if the person is not a felon. Would-be administrators also could be blocked over a conflict of interest, “drunkenness” and “lack of integrity,” state law says.

Moore, Sauerland and their associate Adam Fenn of Compass Realty contend they are finding buyers for abandoned houses that can be taken over by squatters, fall into disrepair and become a neighborhood nuisance.

VanOrman-Wasano also noted that it can take a while to get a court hearing on a sale and that sometimes she worries the homes can fall prey to squatters or vandals or end up in foreclosure.

Moore, who is 41 and now lives in Washington state, said his legal counsel recommended using independent administration because of the issues with abandoned real estate.

“Moving quickly was in the best interest of the situation due to debt accruing daily and the condition of each property deteriorating daily,” he told the Review-Journal in an email.

More often than not, heirs received nothing from his probate sales.

Moore sold 230-plus homes through probate court. On at least 164 occasions, he reported having nothing to distribute to heirs because he sold the home in a short sale, court records indicate.

In such transactions, lenders approve a sale for less than what’s owed on the seller’s mortgage, typically because the property value fell.

Sauerland also pointed to problems the homes can face after the owners die and said the sooner the properties are dealt with the better.

“It’s a quicker process, but that’s not to mean that we’re trying to race to the end and just make a bunch of money and run away,” she said.

According to Sauerland, 65 percent of her sales had equity for the estate.

Overall, the court’s probate workload is plenty high: As of 2022, three judges presided over 10,000-plus probate cases in District Court.

Probate judges, including Gloria Sturman, who took the bench in 2011, and Jessica Peterson, who took the bench in 2021, and Probate Commissioner James Fontano did not respond to requests for comment.

Fontano was appointed to the job in fall 2022. As Price described it, he implemented the new requirements after consulting with judges.

Former Probate Commissioner Wesley Yamashita, who held the job from 2008 to 2021, declined to comment.

‘Some formalities can be relaxed’

In 2011, Senate Bill 221 made various changes related to trusts and estates. Among other things, it contained the Independent Administration of Estates Act, which allowed a personal representative to administer “most aspects” of a dead person’s estate “without court supervision.”

After the bill was introduced, the State Bar of Nevada said the independent provision was designed to expedite probate cases, reduce burdens on the court and lower administrative costs by allowing a personal representative “to act more independently from the court in non-contested matters.”

“In many estates, court supervision is neither helpful nor necessary, and some formalities can be relaxed without any detriment to the interested parties,” according to a summary the legal group provided.

There may have been some attorneys who voiced concern about independent administration at the time, but the State Bar’s probate and trust section felt the “benefits outweighed the burdens” of “what could go wrong,” said Reno attorney Julia Gold, one of the lawyers who pushed for the change.

Gold said she has heard that Las Vegas gets some “disturbing” probate cases. But overall, independent administration fulfills its intention of lowering expenses and getting more money to beneficiaries, she contends.

“If it’s used properly, it serves its purpose, and it serves it well,” she said.

Las Vegas Review-Journal

The Review-Journal’s investigation of homes sold through probate court found many cases had ties to the same Las Vegas real estate firm: Compass Realty & Management.

Compass earned commissions in more than 100 probate cases managed by Estate Administration Services founder Thomas G. Moore, who said in court papers that he “passed the torch” for his probate work in 2020 to his former colleague Cynthia “Cyndi” Sauerland.

Sauerland, an agent with Compass, has sold more than 100 homes through probate court, including at least two dozen to her associate Adam Fenn of Compass, who flipped most of them, and one to Compass owner Takumba Britt, the Review-Journal found.

Sauerland said that Compass handles the listings when she sells homes through probate.

“It’s every time,” she told the Review-Journal. “This company knows what they’re doing with these properties.”

In one 2022 case, District Judge Jessica Peterson said in court that she had a “big problem” if Sauerland worked for the real estate firm that handled the sale, adding it was a conflict of interest with Sauerland’s position.

Britt told the Review-Journal that he doesn’t believe there are any conflicts of interest with his company’s probate work.

When someone has a niche and puts a house on the market, he said, it is “still getting sold and still getting the most for the heirs.”

Fenn added: “It’s still good business, that’s what we’re doing here. We’re providing value.”

Police calls and code enforcement

In Britt’s case, he bought a one-story house in Henderson that belonged to Louis Armendariz, who died at age 90 in fall 2020, records show.

Sauerland obtained court authority to oversee Armendariz’s probate case in early 2022 and then sold the dead man’s house through the case to Britt that summer for $400,000, property records show.

He still owns it and said he’s renovating it.

Moore, Sauerland and Fenn said the homes they deal with in probate are often dilapidated and prone to squatters moving in. City records show Armendariz’s house was a magnet for problems after he died and before Britt purchased it.

Police received calls for disturbances, domestic battery and other reported issues at that address in 2021 and a narcotics call in early 2022, Henderson call logs show.

Henderson’s code enforcement division also issued a violation notice in the spring of 2022 that cited substandard living conditions, litter and debris.

During a visit there, officers observed soiled carpeting, shopping carts, deteriorating furniture and an extension cord that came out of a window and led to a neighbor’s backyard.

Code enforcement officers visited again two days later, joined by police, and met two occupants of the home. After the officials were allowed in for an inspection — the house was a mess and had at least one fire hazard — they deemed it unsafe to occupy.

The occupants gathered a few personal belongings and left.

Robert Telles makes claims

Former Clark County Public Administrator Robert Telles, who often tried to block Moore and Sauerland’s efforts to land cases, has been jailed for more than a year on allegations that he murdered Review-Journal investigative reporter Jeff German.

Telles alleged at a court hearing in his murder case this month, without offering any evidence, that he believes Compass “framed” him for the slaying.

Until he was arrested, he was “pursuing exposure of Compass Realty’s thievery in probate cases,” he said in court.

Compass was opening cases to sell the homes of dead people to its partners at low prices with no public auction so the buyers could later resell the homes for as much as double, Telles said at the hearing.

“The money that should have been going to families was going into the pockets of these guys,” Telles claimed.

Compass was not a party to the hearing, and no one representing the company was in court at the time to respond.

Telles has also claimed that what prosecutors called “overwhelming evidence” against him was planted at his home.

Britt said in a statement to the Review-Journal after the court hearing this month that Telles is a “desperate man who has been charged with violently murdering a beloved local journalist,” and that it appears he will “do and say anything to escape answering for this charge.”

Britt also said Telles “harassed” Compass and its agents while in office and fought with the company in court over the administration of probate cases.

It is “unconscionable and irresponsible” for Telles to accuse Compass of anything, said Britt, who added that the company was “evaluating its legal options.”

Contact Eli Segall at esegall@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0342. Segall is a reporter on the Review-Journal’s investigative team, focusing on reporting that holds leaders, businesses and agencies accountable and exposes wrongdoing. Michael Scott Davidson was the Review-Journal’s data/watchdog editor. Review-Journal staff writer Brett Clarkson contributed to this report.