Summerlin nursing home says it’s not liable in COVID death lawsuits

A Las Vegas nursing home where 30 residents died from COVID-19 is facing several negligence lawsuits, but the facility asserts it is protected from the claims because it followed federal safety directives.

The Heights of Summerlin, one of two skilled nursing facilities tied for the state’s deadliest coronavirus outbreak, is arguing that a longstanding law guarantees it the same liability protections as companies like COVID-19 vaccine manufacturers, according to court documents.

At least seven families have sued the 190-bed facility for negligence since February. That includes five wrongful death claims for patients who died after becoming infected.

“We’ve had no closure, we’ve had no resolve, we’ve had no peace,” said Sylvia Smith, a litigant whose father died in April 2020. “It’s the family’s responsibility to fight for their family, dead or alive. And that’s what we’re doing.”

More than 100 residents at the Heights have tested positive for COVID-19 since the pandemic began, according to data public health officials released this week. Nearly half of its 200-member staff have also been infected.

A 2020 investigative report by the Nevada Department of Health and Human Services found alarming deficiencies at the Heights: Staff members were not properly fitted for N95 face masks in quarantine areas, staff improperly wore isolation gowns and jumpsuits and did not socially distance themselves after working with infected residents. Officials also found a lack of timely, accurate reporting of COVID-19 cases and related deaths to the state.

That report and Review-Journal interviews with current and former staff and patients painted a picture of a facility where the most basic safety precautions were ignored — both before and after the coronavirus invasion.

But the Heights is invoking the Public Readiness and Emergency Preparedness Act (PREP Act), a longstanding federal law that is meant to shield companies fighting public health emergencies.

The statute was expanded in 2020 to limit health providers’ exposure to coronavirus-related lawsuits. In January, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services clarified that nursing homes and other facilities are immune from liability, except for cases where virus mitigation measures were totally disregarded.

“The PREP Act is designed to enable healthcare providers, including skilled nursing facilities, to focus on using every available means to combat a pandemic and save lives without being chilled in their efforts by the threat of lawsuits,” Heights attorney David Mortensen wrote in court filings, requesting that all five wrongful deaths lawsuits be dismissed. He declined to comment for this story.

Legal experts say the defense is aimed to capitalize on the uncertainty of the law and is likely to ultimately be decided by the U.S. Supreme Court.

“They’re going for a form of protection that doesn’t require them to defend their underlying conduct,” said Georgetown University law professor Heidi Li Feldman. “That’s strategically clever of them.”

In essence, Feldman said, nursing homes invoking the PREP Act could “run out the clock” by drawing out the legal process and deterring more people from filing suit.

Heights administrator Latoya Davis, who is named as a defendant in each lawsuit, declined to comment for this story. Representatives for the facility’s parent companies and co-defendants, Summit Care LLC and Genesis Healthcare, also declined to comment.

Litigation in flux

The last days of some of the patients who died after catching COVID-19 at the Heights are detailed in court documents.

Sally Lou Scanlon, 80, tested positive weeks after being admitted to the nursing home. Her doctor did not sign that he was notified of the diagnosis until five days later, records show. She died May 6, 2020.

Phyllis Wyant, who had a small stress fracture in her back, needed six weeks of rehabilitation. But instead the 80-year-old was discharged with a cough after just four days.

“It went from a cough to pneumonia to COVID to dead in five days,” her daughter, Tracy LaMonica, recalled later.

Aletha Porcaro, 82, died April 21 — a week after she was discharged from the Heights to a senior living complex. She was not tested or screened for the disease before she left, a lawsuit states.

On July 25, Rita Esparza also died from COVID-19 after contracting it at the Heights. She was 70.

Maria Alimusa, also 70, was one of the first Heights patients to die from COVID-19. Before she was transferred to the hospital, she left her son a voicemail.

“It’s really getting bad here,” she said. She died April 14.

Court records show that Alimusa’s family is involved in one of at least five arbitration cases against the facility. In those cases, the patients signed a four-page arbitration form presented to them when they were admitted.

“It entitles the Heights to basically avoid a jury trial and set up a very questionable system of justice,” said Alimusa family attorney Robert Murdock. “To me, it’s another form of elder abuse.”

In a May 2020 statement, former Heights administrator Andrew Reese emphasized that the facility had been fully transparent and forthcoming in sharing information with patients, residents and families.

“I can assure you that we are working around the clock, doing everything in our power — and everything medical experts know as of this time — to protect and keep our patients, residents and employees as healthy and as safe as possible,” he said.

Reese left his position in late August 2020 after state officials discovered a number of safety deficiencies at the facility, laid out in the 26-page investigative report first reported by the Review-Journal.

New lawsuits

The lawsuits also allege that investigators found the facility continued to accept new patients even as COVID-19 decimated those already living there. Employees did not don protective gear or screen residents’ temperatures until early April 2020.

Court filings also allege the facility was so understaffed that nurses were caring for more than 30 patients at once.

Attorneys for the families of patients argued in court documents that the PREP Act doesn’t apply because the deaths occurred due to the Heights’ “inaction, rather than action.”

“This failure to develop and follow an infection control program does not fall under any of the ‘covered countermeasures,’” attorney Jamie Cogburn wrote.

Mortensen disagreed, noting that the nursing home used “covered countermeasures” recommended to them by the state and federal government to combat the virus, including the use and distribution of protective gear, providing COVID-19 tests and other safety protocols.

“These very detailed clinical directives and instructions represented a marked departure from the regulatory structure which existed before the pandemic,” he wrote in court records.

Precedent-setting opinion

As nursing homes face scores of lawsuits nationwide, the PREP Act argument is only now starting to be tested.

In a precedent-setting opinion last week, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 3rd Circuit upheld a New Jersey federal court’s ruling and rejected two nursing homes’ bid to stay in federal court under the PREP Act.

The decision only applies to courts in the 3rd Circuit and means the wrongful death cases must play out in state court. While the news will certainly be influential in other cases, experts say circuits can disagree.

“The HHS opinion is helpful to nursing home defendants, but they’re facing an uphill battle,” said David Orentlicher, the director of the health law program at UNLV. “They’re pushing a very minority viewpoint, so it’s unlikely they’ll succeed.”

The argument has so far been denied in about 50 cases nationwide.

In Nevada, U.S. District Judge James Mahan made a similar ruling against the Heights’ sister property in Las Vegas, St. Joseph Transitional Rehabilitation Center. In that facility, 12 residents and one staff member have died from the disease, according to state health data.

Mahan wrote in his decision this month that isolation and social distancing measures are not considered covered countermeasures under the PREP Act.

A single case heard in the Central District of California earlier has upheld the nursing home’s argument, reasoning that a facility’s failure to properly screen visitors, supply protective gear and maintain COVID-19 preventive protocols were “unsuccessful attempts to administer countermeasures,” as opposed to the failure to administer countermeasures.

Because Nevada and California fall under the 9th Circuit, that creates an unsettled state of the law, said Feldman, the law professor at Georgetown.

“The more the law is unsettled, the more that benefits the nursing home industry,” she said.

‘He did not have to die’

Sylvia Smith said she didn’t know her father had COVID-19 until he was already dying from it.

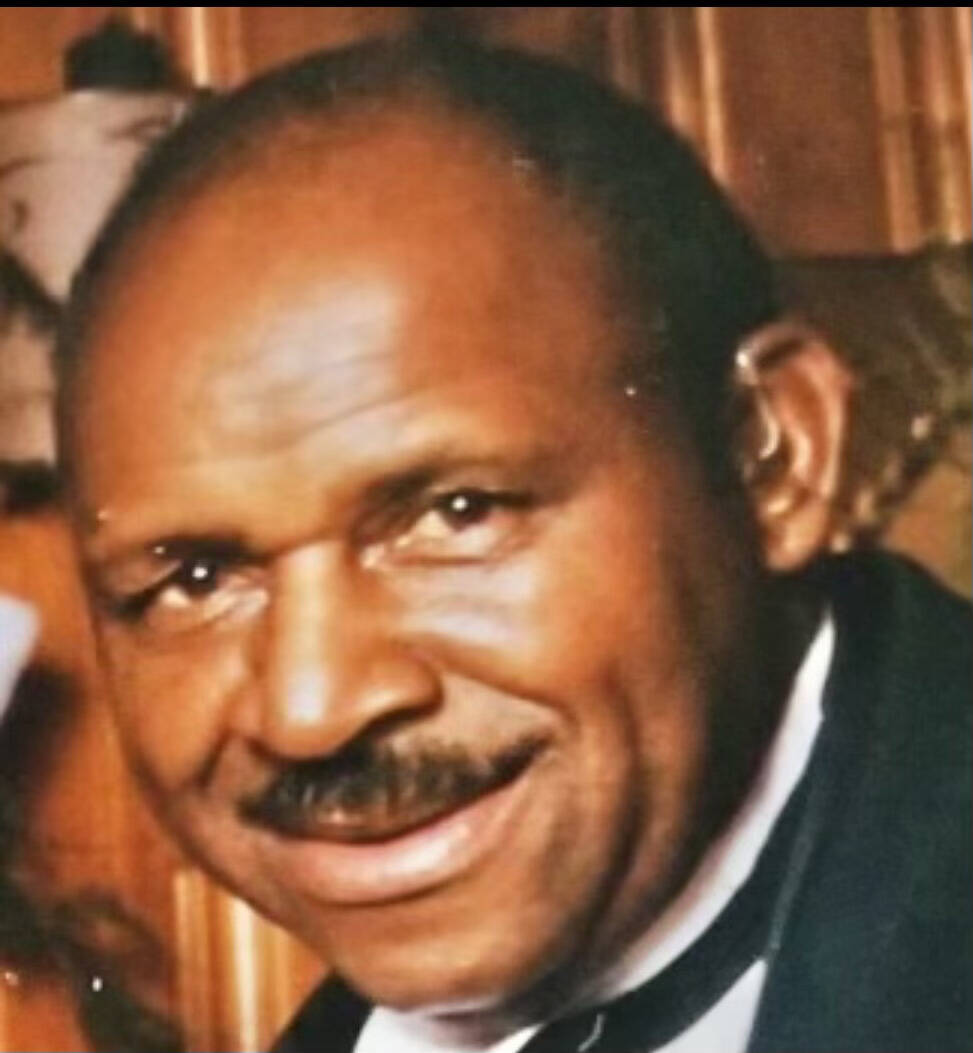

When George Woods, 85, was first admitted to Summerlin Hospital Medical Center on April 16, 2020, his family was told he was lethargic and appeared to have kidney trouble.

Based on what they were told, Woods’ family said they thought he would return home, that he’d be fine.

But Heights’ staff had already reported to the hospital that Woods had been tested for COVID-19 and was being transferred for evaluation and treatment, according to the lawsuit filed by Smith’s attorney, F. Travis Buchanan.

Woods’ positive diagnosis on April 18 came as a shock to Smith, who said she was assured by staff members there was only one isolated case at the nursing home. He died the next day.

By then, there were at least four confirmed cases in the facility, court records show.

Smith said her father saw the positive in everything, even when he developed spinal stenosis and lost his ability to walk in 2011.

“He never met a stranger,” she said. “People asked him, ‘Do you ever get angry about anything?’ And he’d smile and say, ‘About what?’”

The Heights was close to his family, who visited him on a daily basis until the facility closed to visitors in March. In his last moments, Smith told him she loved him through the phone.

She keeps his ashes on her fireplace mantel.

“It’s a great reminder,” she said. “He did not have to die.”

The wrongful death cases against the Heights are still pending in federal court, waiting for a judge to decide if they’re in the right venue.

Briana Erickson is a member of the Review-Journal’s investigative team, focusing on reporting that holds leaders and agencies accountable and exposes wrongdoing. Contact her at berickson@reviewjournal.com or 702-387-5244. Follow @ByBrianaE on Twitter.