Assigning blame is human response to ambiguity

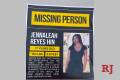

Cho Seung-Hui. College senior at Virginia Tech. Crazy person who shoots people at random for no reason except that he's crazy.

Within a couple of hours of the April 16 horror and mayhem at Virgina Tech University, people were criticizing the university leadership for not warning the student body in a way sufficiently speedy and comprehensive. As I read the news stories flowing in, I remember thinking, here we go again. The human way to respond to ambiguity -- in this case, the ambiguity of evil -- is to retrofit a failed expectation of preventability. To assign blame.

Ambiguity, by definition, is not in our sphere of control. And when we suffer something beyond our control, it is common, then, to assuage ourselves by quickly assembling stories saying we should have been able to control it.

We should have been able to control the events surrounding 9/11, so now it takes three hours to get on an airplane. We should have been able to prevent childhood sexual abuse, so now we insulate and sterilize all relationships between children and the adults who love and care for them. We should have been able to prevent the burned thighs of The Lady Cradling McDonald's Coffee Between Her Legs in the Car, so now everybody gets tepid coffee.

It's the American way. We're too cool to suffer ambiguity. Pile on.

But then more stories trickled in. Professors and classmates began to share stories about Cho. I began to get a creepy feeling. I didn't think the authorities deserved to be criticized.

I began to wonder if we did. Let me explain ...

Twice in my life an employer has directed me to attend first aid/CPR training as a prerequisite for employment. I learned about broken bones, cuts and bleeding. I practiced mouth-to-mouth resuscitation with the head and torso of this very attractive blonde made of plastic and rubber. I learned about poisons, venom and allergic reactions. I learned to tell the difference between heat stroke and heat exhaustion. Then back to Plastic Blonde Lady, beating on her sternum because she'd just had a heart attack.

My employer paid for me to be in this training all day. Somewhere up in the hierarchy someone had decided that, in the event of trauma or health crisis, the employees should know to do more than just wring their hands and stare.

Later in my career, I crossed paths with the American Association of Suicidology. I "took up a torch," as it were, for suicide prevention. When it comes to suicide threats and warning signs, my relentless message to this culture is never do nothing. Ask. Act. Intervene. Give me two, three hours, a white board and a dry erase marker, and I can teach most anyone the rudiments of suicide assessment and intervention. I do it all the time.

Training in suicide assessment and intervention should be required of each and every junior high, high school and college instructor. In the same way and for the same reasons that my employer believed I should know basic first aid/CPR. Given the grim statistics regarding adolescent suicide in America, it's a dereliction of duty not to know how to recognize the warning signs, not to know what to do.

Which leaves me wanting to ask: Should educators and corporate employers receive training to recognize the signs of decompensation? (That's the fancy word for "going crazy.") To hear it tell, a ton of folks observed and were concerned about Cho's bizarre behavior. But very few recognized the real pathology of what they were seeing.

I ask again: Should we rightly expect educators and employers to have training in the rudiments of mental health assessment? Would that spare us from a least some of these senseless and devastating assaults on the public?

I'm really asking.

But maybe I, too, am grasping at straws. It is the nature of evil to be both subtle and banal. By the time evil is recognized as evil, it is often too late.

Two days after the Virginia Tech shooting, I took my son to high school. The campus was swarming with police officers. Every street onto campus was blocked by two squad cars. The officers were holding M-16s.

"What's going on?" I said to my firstborn.

"I don't know," he said. He got out of my car, and walked toward the band room. And I let him go. To his death, maybe.

Turned out to be a staged drunken driving death, offered by the police department to educate young people.

Terrible timing.

Steven Kalas is a behavioral health consultant and counselor at Clear View Counseling and Wellness Center in Las Vegas. His columns appear on Tuesdays and Sundays. Questions for the Asking Human Matters column or comments can be e-mailed to skalas@reviewjournal.com.

STEVEN KALASHuman MattersMORE COLUMNS