Advocates help students with health conditions get care they need

When Irene C. Smith found out that her 14-year-old son had Type 1 diabetes, she vowed not to sit around and feel sorry for herself. When problems arose at her son’s school in New Jersey, she realized the disease itself was only the beginning of the struggle.

The family moved from New Jersey to Nevada 14 years ago, hoping that the school situation might be better here. It wasn’t.

“Parents feel intimidated,” said Smith, now the American Diabetes Association of Nevada chairwoman and advocacy chairwoman. “They don’t even know they have rights. So that’s what we try to explain to them. But we also want to work with the school. We don’t want to cause problems.”

As an advocate, Smith works to ensure that kids with diabetes get their needs met in the school system, without discrimination. But diabetes is only one of many conditions, encompassing everything from cancer to dyslexia and autism, that can cause problems for kids in school — sometimes spelling disaster for families.

Federal law — including Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act of 2004, and the Americans with Disabilities Act Amendments Act of 2008 — requires federally funded schools to provide accommodations, and ensures services to more than 6.5 million infants, toddlers, children and young people with disabilities.

But translating law into a typical school day in Clark County isn’t always easy.

For example, no one but the school nurse is permitted to administer an insulin shot to a student with diabetes, Smith said. That’s a problem, she said, when the school nurse-to-child ratio is approximately 1-to-1,800.

“A student that has diabetes has no one to administer insulin when the nurse is not there, so the parents are constantly called to administer insulin, or take their child home,” she said. “There are parents that are called three to four times a week.”

Smith said many of those parents are in danger of losing jobs, have resorted to home schooling, or have moved away because the school has a nurse only one day a week. The situation threatens a family’s economic survival — and a child’s shot at an uninterrupted, equal- opportunity education.

Advocates like her often go the extra mile that eludes the average parent. In a 2005 case involving a 5-year-old, the school informed her that the rules couldn’t change — unless she convinced the Nevada State Board of Nursing. She did, and won.

Another of Smith’s sons was diagnosed with Type I diabetes in 2008, at age 32. She received the call on the Hill, while prodding Congress for funding and legislation.

That kind of “luck” has driven her to fight harder, most recently for SB 320, sponsored by Senate Majority Leader Mo Denis, D-Las Vegas, and Senate Minority Whip Dr. Joe Hardy, R-Boulder City. Nevada legislators are currently considering the legislation. It allows nonmedical personnel to administer insulin shots, and gives kids with diabetes the go-ahead to self-administer in school, with permission from a doctor. If it passes, Nevada will join 19 other states that already have those measures in place, Smith said.

Advocacy makes a difference even closer to home, for parents who call the local American Diabetes Association office for help. Through a campaign called “Safe at School,” the organization provides a range of resources, including whatever’s necessary to train school staff. And Smith helps parents address the 504 plan, an agreement to ensure that students with issues such as diabetes get the same education as their peers.

Within a day or so of making that call, said parent Jeanie Richardson, Smith was at her house. Richardson’s 14-year-old daughter, Samantha, was diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes earlier this year.

Richardson asked the school counselor whether her daughter needed a 504.

“The counselor said to me, ‘I don’t think so. Everyone’s pretty nice around here,’ ” she remembered.

But when her daughter returned to school, the choir teacher stopped her from going to test her blood sugar.

“She’s nervous and she’s self-conscious and she’s fumbling,” Richardson said. “Sure, is he a nice guy? Yeah. Does he have health issues? Probably.”

Her daughter waited 10 minutes, a potentially dangerous time gap. Richardson suspected that many of the teachers weren’t familiar with the disease.

Samantha’s 504 now allows her to test in class or dismiss herself and go to the nurse’s office. The finalized plan emerged from a meeting that included eight teachers, the vice principal, school counselor, school nurse, Samantha, her best friend, both parents and Smith, Richardson noted. Wherever staff pointed out that a detail was already referenced in school district policy, she pulled up the policy and asked to have it explained.

She appreciates the school for getting that many people together, and for the actions that have followed, she said. But buyer beware.

“I think that people don’t want to fight,” she observed. “Do I also think that they don’t want a 504? Probably.”

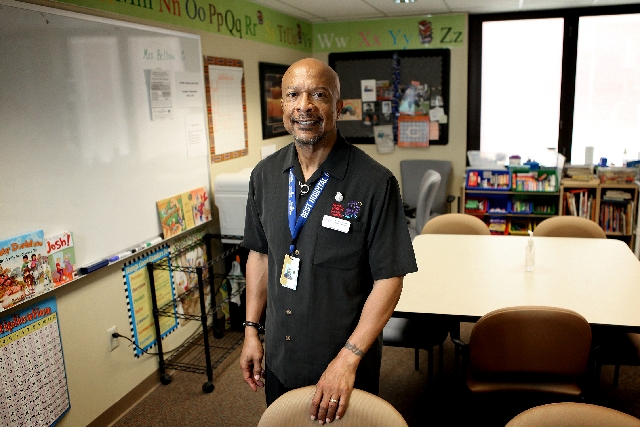

Dr. Alvin W. Mathews, a former assistant principal with a 33-year education career, has sat on both sides of the table. Now the education director at the nonprofit Nevada Childhood Cancer Foundation, he’s attended approximately 17 school meetings this year, often dealing with 504 plans or the more stringent individual education plan for kids with particularly complex issues.

“When I was an administrator with the district, when you mentioned that an advocate was coming with a parent, it wasn’t always looked on favorably,” he admitted.

At the top of his list, these days: helping school staff and administrators “understand more of what a child is going through. Cancer is just so devastating. It’s devastating to the parent, financially, emotionally, and not to mention, it affects siblings.”

He arrives at meetings with concrete evidence, including neuropsychological test results, provided free of charge by the foundation. Most insurance companies don’t cover the testing, he said.

But for kids trying to juggle school and cancer treatment, those tests can make a powerful statement about the ordeal’s effect on their brain.

“As a result of the meetings, their grades have tended to improve, of course,” he said. “And I’ve been able to help some of our senior high school students apply for scholarships.”

Joanne Vattiato, director at the Clark County School District’s Student Support Services division, added: “It’s our obligation to teach all children. It’s our job to make sure that we have the supports, resources, training to make sure that student is successful.”

The school district addresses its school nurse limitations by tracking what students are in what locations, and providing the appropriate resources in those locations, she explained.

If a parent complains that a teacher hasn’t followed the plan, she said, another meeting will take place, to discuss concerns, make adjustments, or agree on courses to continue.

But the length of resolution time can frustrate parents. Smith still remembers the parent who had a problem with a school nurse that dragged on for five years. It took Smith a month to help resolve it.

“This is a comprehensive, difficult, meaningful process,” Vattiato said. “So the way that I like to address that, when people have different ideas, is to remember to always bring it back to the child.”

Parents often have advocates for a variety of noncontentious reasons, she said, such as the need to have another person at the meeting for confirmation, to bounce ideas, or to understand.

“If a parent is not familiar with the law or needs some additional assistance, absolutely, I would recommend that they have an advocate,” she said.

The district offers information about Nevada Parents Encouraging Parents, a nonprofit that provides services and classes to help families understand both 504 plans and individual education plans.

Robin Kincaid, Parents Encouraging Parents’ training services director, said the organization has helped thousands of families. Staff members are parents of children with disabilities, or have a family member dealing with an issue. Or, they’re a person with a disability.

For Smith, advocacy is about the feeling she gets driving down the road.

“I’m like, ‘We did it, we did it again,’ ” she said, laughing. “This child’s gonna have a better situation in school now.”