NBA legend still a game-changer, but now the game is health care

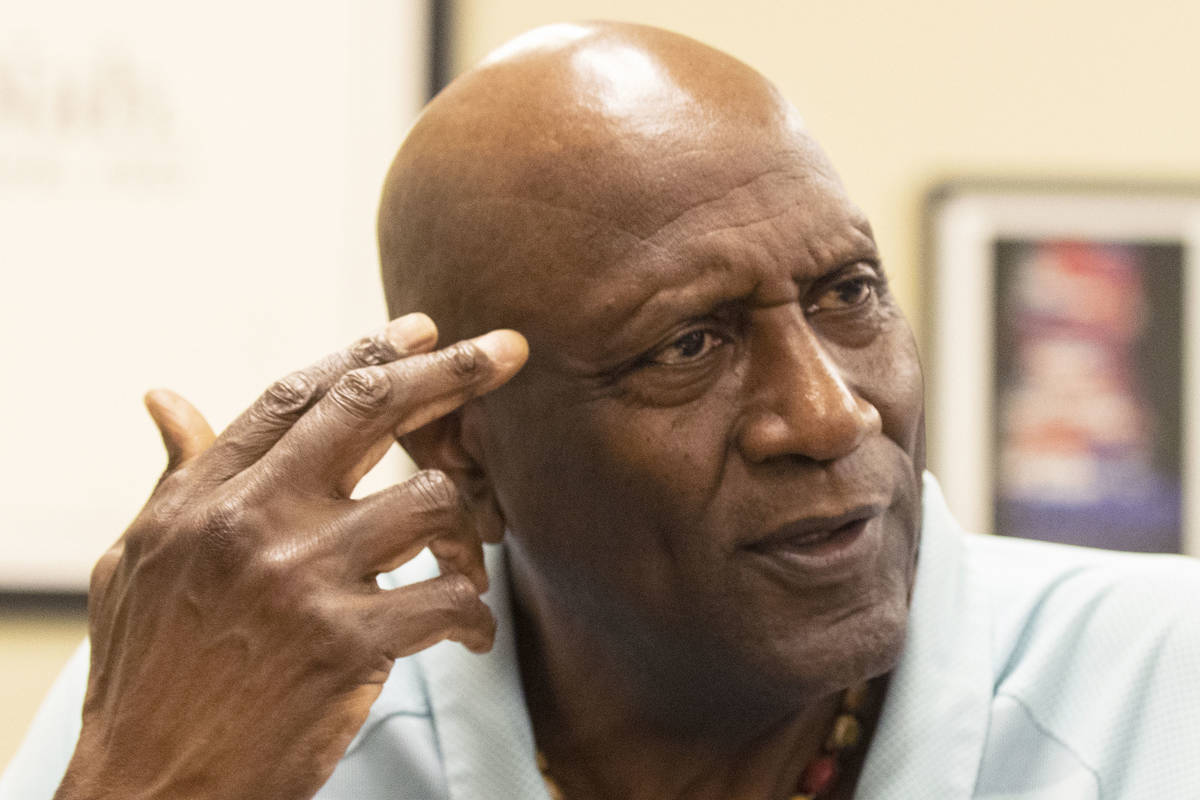

Spencer Haywood played 12 seasons in the NBA and in four NBA All-Star games. He won an Olympic gold medal in 1968 and an NBA title in 1980 with the L.A. Lakers. He was inducted into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame in 2015. And, through a legal challenge that made it to the U.S. Supreme Court, Haywood transformed the NBA and made millionaires of a generation or two of NBA superstars who followed.

But none of that particularly impressed his daughter, Shaakira, a New York City psychologist.

“She said, ‘You’re always talking about how you helped the NBA players with the Supreme Court ruling, and you helped make them $31 billion. When are you going to do something for real?’ ” Haywood says, laughing.

“I went to the Supreme Court, and ‘When are you going to do something for real?’ “

Thanks to Shaakira’s prodding — and, probably, his own inclination toward advocacy — Haywood now is playing for different, more significant wins as a member of the Dean’s Advisory Council for Roseman University College of Medicine.

There, the longtime Las Vegas resident is helping encourage minority students to pursue careers in medicine and working to improve health care for underserved and at-risk minority Southern Nevadans. Also, he is involved with the school’s outreach initiatives and already has appeared in Roseman’s public service campaign to encourage Southern Nevadans to receive COVID vaccinations.

They’re new but characteristically game-changing moves for Haywood, 72, who, growing up poor, didn’t even go to a doctor or dentist until he was a teenager.

Hard work

Haywood was born a sharecropper’s son in Silver City, Miss., population 275, and, he says, “I’d remind you, there was no silver and there ain’t no city.” His father died about a month before Haywood was born, leaving his mother to raise 10 children in tough circumstances.

“We were cotton pickers, full-fledged cotton-picker slaves,” Haywood says. “I started picking cotton when I was 3 and picked until I was 15, sunup to sundown, all day, sleep at night and get up and do the routine again.

“So I learned from that hard work,” Haywood says. Later, when coaches would threaten, “‘We’re going to run you hard today for three hours,’ like, you’re talking three hours? You’re going to kill me in three hours? Bring it on.”

Early on, Haywood devoted his energy to sports, and his talent eventually took him to Michigan to play high school ball,

“I didn’t see a doctor or a dentist until I was 14 and leaving Mississippi,” he says. “My mom, if the kids got sick, (said) ‘Let me get some burdock root, let me get this, let me get that.’ It was holistic.

“There wasn’t a doctor or a dentist. You could go to a vet. He’d look at a little cavity in your mouth … (and) just yank it out.”

The (Supreme) Court

In 1968, Haywood won a gold medal as the youngest player on the U.S. Olympic basketball team. His pro career included stops with the ABA’s Denver Rockets and the NBA’s Seattle SuperSonics, New York Knicks, Los Angeles Lakers, New Orleans Jazz and Washington Bullets. He won an NBA title in 1980 with the Lakers and was a four-time NBA All-Star.

But Haywood also made an impact off the court when he challenged an NBA rule that prohibited players from playing in the league until they were four years removed from high school. Haywood figures his 1971 legal victory resulted in more than $31 billion in player salaries in the years since.

Not surprisingly, staying in top shape was a priority during his playing days. “I was always concerned about health,” Haywood says.

“Then, when I got with the Lakers, I took a wrong turn. I decided I wanted to party with the Hollywood people. I wanted to just be like my heroes on the big screen, and what they were doing? They were doing cocaine, and I was like, ‘Well, let me do some of it, too. It’s going to enhance my life.’ “

Instead, Haywood says, “it took my life through what I would say is a living hell.”

At the time, Haywood was married to the fashion model Iman, who suggested that he see a psychiatrist or psychologist. “I was, like, ‘You’re really talking crazy … because I ain’t got a problem,’ but I do have a problem. Denial.”

Haywood did see a therapist, “and I fell in love with it. All this (expletive) I’ve been carrying, I can dump it on somebody? A light went on in my head.”

A new game

Haywood’s work with Roseman began after he went to the school’s Summerlin campus in February for his first COVID vaccination.

“I took my shot on camera, (to say) ‘Please, look at me. I’m here, I’m getting the vaccine. It’s safe, we need to do this for our country to survive.’ ”

Dr. Pedro “Joe” Greer Jr., founding dean of Roseman University College of Medicine, asked Haywood to serve on the Dean’s Advisory Council to assist with the school’s minority recruitment programs.

“I truly need his advice (about the) intersection between society and medicine, what we have done wrong, how do we get it right, how do we get students who are under-represented minorities in medical school,” Greer says.

According to the Association of American Medical Colleges, only 5 percent of active physicians in the United States in 2018 identified as Black or African American, while just 5.8 percent identified as Hispanic.

A absence of minority doctors and health care professionals can reinforce patients’ mistrust or disconnection from the health care system. Conversely, Greer says, minority physicians “bring a sense of trust to the communities that are most vulnerable. Trust is such an important component.”

Minority doctors and health care professionals also can break down language barriers that can keep minorities from accessing health care, Haywood says. He says one possibility can be adapting to medical education the model used in sports, in which promising athletes as young as 12 or 13 are identified, trained and mentored over time.

Meanwhile, members of at-risk communities need access to accurate medical information, says Haywood, who has talked with African Americans who are skeptical about getting COVID vaccinations.

While that might have something to do with, for example, the legacy of the Tuskegee study — in which syphilis was left untreated in Black men even after treatments became available, in order to gauge the disease’s effects — Haywood says some told him they don’t get medical information from their doctor “because I don’t go to a doctor. I get it from social media.”

“I hear that from the white community as well,” Haywood adds, so health care professionals also are “dealing with the legacy of the internet. (People are) getting their information from the internet.”

Contact John Przybys at jprzybys@reviewjournal.com. Follow @JJPrzybys on Twitter.