Ruvo Center conducts trial to see if cancer remedy can treat Alzheimer’s

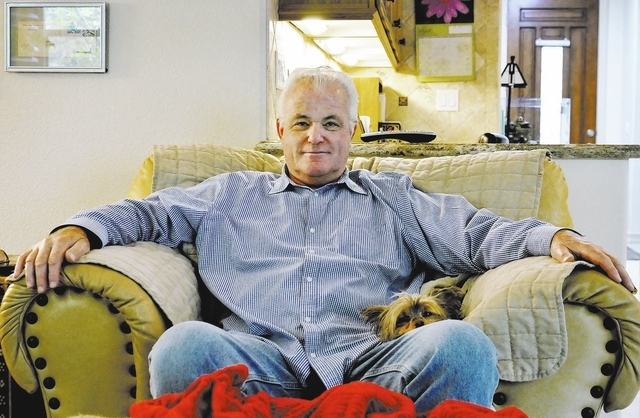

Harvey Levy, an electrician by trade, was so articulate that when he went to court in a dispute, his lawyer let him argue most of the case.

“My husband was quick on his feet, had a way with words, remembered every detail of things,” Jane Levy says as she sits across from her husband of 45 years. “That’s why he won that case he’s referring to.”

A sunbeam breaking through a largely covered window of the Levy’s Henderson home places the retired 69-year-old electrician in a soft spotlight. He smiles at the appraisal of his wife, a retired special education teaching assistant.

“I used to be able to talk very well,” Harvey Levy says, nodding. “Now I have a problem with my brain. I fade out all the time. Once in a while I can’t even talk.”

The problem, Jane Levy recalls, seemed to come on slowly. Like many married couples, they knew each other so well they had become used to finishing each other’s sentences. One day, however, she realized that the father of their three children couldn’t finish his own sentences if he wanted to.

“It was so frustrating for me to see and listen to him that way,” she says. “I knew how eloquent he was and now he wasn’t. His father had the same trouble.”

Frightened, Jane Levy called the Cleveland Clinic Lou Ruvo Center for Brain Health and got an appointment for her husband. Testing would show that Harvey Levy was in the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease, a progressive and fatal brain disorder that now kills more than 80,000 Americans each year.

The Ruvo Center is a leader in trials of drugs to combat the incurable disease. So the Levys decided to try to find a trial in which Harvey Levy could participate this year.

It turned out the state of his disease made him a fit for a clinical trial of the drug bexarotene, a cancer drug touted as a potential treatment for Alzheimer’s. The Ruvo Center trial still needs at least 15 more volunteers.

“It’s really given us hope for the future,” Jane Levy says.

Bexarotene is being tested, said Dr. Kate Zhong, the Ruvo Center’s senior director of clinical research and development, simply because preliminary research on the drug produced phenomenal results.

In 2012, the journal Science published the results of research done on the drug in mice by Gary Landreth, a neuroscientist at Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine in Cleveland.

That study reported that bexarotene could clear 50 percent of amyloid plaques — sticky clumps of the protein thought to interfere with brain function — in as little as 72 hours, and lower brain concentrations of B-amyloid protein, long suspected as a significant contributor to Alzheimer’s disease and reverse cognitive impairments.

Although the journal Nature reported in May that analyses from four independent research groups couldn’t fully replicate Landreth’s findings, both Zhong and Dr. Jeffrey Cummings, the Ruvo Center’s director, say a study in humans still makes sense.

Cummings, who has confidence in Landreth’s original observations, says that what can keep results from being reproduced “is a lack of appropriate rigor” by researchers. If mice are of a different age or a different species, or if different formulations of the drug are used, he says it’s impossible to conduct the same experiment that produced particular results.

None of the follow-up studies in mice replicated the clearance of 50 percent of amyloid plaques in three days, which had some researchers calling Landreth’s work “a hoax.” But Cummings points out that memory was improved “across all the studies” while he says “most” of the other studies confirmed Landreth’s finding that bexarotene reduced levels of B-amyloid protein.

“I see this as still a very viable drug for research,” says Cummings, whose research into Alzheimer’s disease is respected around the world.

What particularly excites Cummings and Zhong about bexarotene, which was originally developed to fight skin cancer, is that it’s part of a National Institutes of Health program to “repurpose” or “reposition” drugs.

In announcing the formal program in 2012, Health and Human Services Secretary Kathleen Sebelius was blunt: “The goal is simple: to see whether we can teach old drugs new tricks.”

The program matches researchers with a selection of molecular compounds from the pharmaceutical industry to test ideas for new therapeutic uses. The ultimate goal is identifying promising new treatments for patients.

“Bexarotene has already been tested for safety, so if it works for Alzheimer’s we can cut years off what it would take to get it to the marketplace,” Zhong says. “Usually, it takes a dozen years or more to get a drug approved.”

Drug repurposing has been going on for years informally.

Requip, first developed as an anti-Parkinson’s treatment, has also found application in treating restless leg syndrome and treating sexual dysfunction caused by certain antidepressant drugs. Gabapentin and its chemical cousin, pregabalin, which were originally developed to fight epilepsy, have found even more use in treating neuropathic pain and anxiety disorders.

Cummings says the formalized drug repurposing program may be just what researchers need to find new ways to combat Alzheimer’s.

“I don’t expect bexarotene to cure Alzheimer’s,” he says as he sits in his office. But he thinks it can open a pathway for exploration “with more powerful drugs.”

Given that the number of Americans living with Alzheimer’s is expected to jump from 5.4 million to 16 million in less than 40 years — with costs of care projected to rise from $200 billion today to $1.1 trillion in 2050 — Cummings says the need for new drugs becomes more critical.

“I still don’t think most people realize how grave the situation is,” he says.

The disease, which causes dramatic problems with memory, thinking and behavior, is the sixth leading cause of death in the United States and the only one of the top 10 without an identified way to cure, prevent or slow its progression.

After testing Harvey Levy, Dr. Charles Bernick, the Ruvo Center’s associate director, placed him on some of the few drugs approved by the FDA. Unfortunately, over the years the drugs have demonstrated only modest effects in modifying clinical symptoms for relatively short periods; none has shown a clear effect on disease progression or prevention.

Levy still ate normally, repaired things around the house, drove the car. He and his wife planned a cruise. But his wife says she found herself under pressure to “speak for him. … He could still do all the physical things, it’s just been the verbal things he couldn’t do.”

In May, Levy became part of the bexarotene drug trial, which lasts about two months for each subject.

“It just seemed like one of the easier trials to get into,” Jane Levy says. “Two pills in the morning, two pills at night. No spinal taps or anything like that. And because the drug is already FDA- approved, if it turns out it works, he could start taking it pretty quickly.”

For the first four weeks, neither Levy nor his wife knew if he was taking a placebo or the drug. During the last six weeks, Jane Levy says she and her husband learned he was taking bexarotene.

As the test progressed, Levy says he noticed that when people talked to him, he could express himself better orally and on paper.

“I was talking to people, and actually writing things down, something I hadn’t been able to do for a while,” he says.

When his time with the drug was done early this summer, Levy says he felt his “brain was in a better place for a while. Now, though, I think I’m going backwards. I’m trying not to, but I can’t find the words again.”

He doesn’t know what scans done of his brain by researchers have shown.

Only when the testing of 15 other subjects is done, probably by year’s end, can Levy have access to the drug again — if testing results show it really helped him.

“I’m sure it did,” Levy says. “I want it again.”

Cummings says researchers must be sure what Levy is describing is not the placebo effect, the beneficial effect in a patient following a particular treatment that arises from the patient’s expectations rather than from the treatment itself.

“What he’s saying, of course, is what we love to hear,” Cumming says. “Let’s hope the testing bears it out.”

Contact reporter Paul Harasim at pharasim@reviewjournal.com or 702-387-2908.