UMC’s nursing chief plays up camaraderie to help staff thrive

As he walks through UMC’s Trauma and Burn Center, Gregg Fusto, the hospital’s chief nursing officer, points to where a trauma surgeon and a nurse massaged a dying teenage boy’s heart with their hands.

It was six years ago, Fusto recalls as he pulls on the left side of his muttonchop sideburns, when 13-year-old Ayren Perry swerved his bike to miss a rock and fell, impaling himself on the right grip of the handlebar. When he pulled the handlebar out of his abdomen, blood gushed into the street.

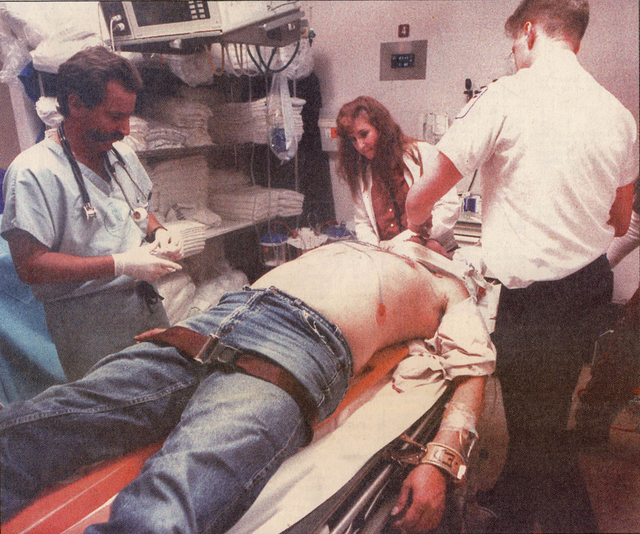

By the time the boy arrived by ambulance at UMC, he had lost nearly all of his five quarts of blood. Then his heart stopped. As more blood was pumped into the boy, Dr. Jay Coates cut open Perry’s chest to massage his heart by hand.

When Coates tired, nurse Tracy Thompson took over as the medical team wheeled the boy from the resuscitation room to the operating room.

“She just got up on the table with him and kept massaging his heart to keep him alive,” Fusto says. “You have to be tough to be a good nurse, ready for anything. And you have to believe in teamwork like Coates and Tracy, have a clear focus and attention to detail. That’s what brings about great medical care, the reason that young man is alive and doing well today.”

Accentuate the positive. Eliminate the negative. That, in a nutshell, is Fusto’s life philosophy and management style, trauma program manager Abby Hudema says.

Fusto, 57, left his position as director of UMC’s nationally recognized trauma unit six months ago when new UMC CEO Lawrence Barnard promoted him to chief nursing officer. Fusto is the first male to hold the position in the hospital’s history.

Fusto, who is married to Las Vegas cardiac and thoracic surgeon Nancy Donahoe, is a former lifeguard, emergency medical technician, paramedic and flight nurse. He’s helped a woman deliver her baby in the shower and had a woman throw up Doritos during mouth-to-mouth resuscitation. He also performed CPR on rapper Tupac Shakur after he was shot in Las Vegas in 1996. Three surgeries couldn’t save the 25-year-old rapper from the fatal damage done by four bullets.

“You love being a nurse when you help people,” Fusto says. “But it’s so hard when they die. I don’t think people realize how difficult it is to keep on going, to be positive, when someone dies that you’re caring for. Not everybody can do it.”

The praising of teamwork that’s kept Ayren Perry and other patients alive isn’t shared just with visitors.

“He never tires of reminding staff of our successes,” says registered nurse Hudema. “Sometimes it’s easy to forget what you did with patients like that Perry boy when you become so busy. He wants us to keep sight of just how important our work is. I don’t think there’s a question in anyone’s mind that he’s sincere.”

Fusto hates that UMC failed a Leapfrog hospital safety survey released a few months ago. But he says he believes the problems the survey highlighted, including patients complaining of unclear care and discharge instructions, are easily correctable.

“We have to listen more,” he says. “Once people see you care about their concerns, much miscommunication goes away.”

He now has nurses making formal rounds each morning to check in on patients. And medical care checklists, much like an airline pilot uses before takeoff so that no steps are ever missed, have taken on more focus.

“What nurses see with Gregg is that he’s not afraid to pitch in,” says Katie Ryan, emergency services director and a registered nurse. “When we’ve gotten overloaded at night — one night we had multiple car accidents, shootings, stabbings — I’ve called him and he just shows up and works, too.”

Fusto grew up as the son of restaurant owners in St. Augustine, Fla., and became an accomplished Italian cook.

“He’ll bring in huge meals that he’s made for staff during tough times and the holidays,” Ryan says. “People look forward to that.”

After promoting Fusto in January, Barnard says a major reason he did so is because of the mutual respect he saw between Fusto and those he supervised.

“It was a kind of mutual admiration society,” he says.

Fusto says he never expected to keep rising in administration.

“I’ve had a real distrust for authority,” he says. “But I’ve learned that you can either keep taking crap or put yourself in a position to change things.”

Fusto admits he had an ulterior motive in training for the first position that had him saving lives.

“I wish I could say I became a lifeguard solely to help people,” he says, laughing. “But I have to tell you that being a teenage lifeguard in Florida has to be the best way to meet girls.”

As a lifeguard, however, he realized saving lives isn’t always romantic. As he gave mouth-to-mouth resuscitation to a girl who nearly drowned, she vomited up Doritos.

“I can’t stand Doritos to this day,” he says.

As a paramedic in Florida, he answered a 911 call to an apartment where a woman was delivering her baby in the shower.

“I got in there with her,” he says, “and her baby came out just fine.”

Six or seven years later when he was near the same apartment complex on a call, a little girl walked up to him with a question: “Do you remember me?” He said he didn’t think so and the girl ran to her mother, who was standing nearby with a big grin on her face.

“The mother gave her a picture and she ran back with it,” Fusto says. “It showed me in the tub with her mother giving birth. I didn’t realize at the time that the mother of the woman I helped in the shower was taking pictures of the whole thing.”

After becoming a nurse — “basically because I could make more money as a nurse than a paramedic” — Fusto occasionally had to deal with jokes about being gay.

“I didn’t get mad about it,” he says. “I just hit on every female nurse and doctor from that point on.”

When he was a flight nurse, one doctor he hit on was Nancy Donahoe.

“We basically met during an argument,” he says. “She said that the patient I brought in to the hospital didn’t have the breathing tube in the right way. I showed her that it was.”

Months later, after dropping off a seriously burned patient at a Gainesville, Fla., hospital where Donahoe then worked, he saw her sitting in the cafeteria and walked over to her. Suffice to say, the couple, now married for 20 years, didn’t argue on that occasion.

Each ultimately got job offers that they took in Las Vegas.

Being married to someone who deals with life and death isn’t always easy, Fusto says.

“We kind of know when the other wants to talk or not,” he says.

Reading thank-you notes written by families of people whose lives were saved can make the loss of a patient more tolerable, Fusto says.

There was one weekend 15 years ago when Fusto would have died if he had followed his planned schedule. He was supposed to be working in Southern Nevada as a flight nurse on April 4, 1999, but he canceled because of other commitments. That helicopter crashed, killing two flight nurses and the pilot.

“My wife said I had to choose between the job and her,” he says. “I haven’t worked as a flight nurse since. She said she didn’t want the stress of worrying about it.”

For years Fusto was concerned about the mental stress that burn patients went through. Though they became well enough to leave the hospital after painful treatments, the mental distress that often accompanied disfiguring scars wasn’t dealt with by the hospital.

“We got a professional counseling volunteer and a child-life specialist to work there and it’s made a big difference,” he says.

Trauma surgeon Coates, who heads the burn center, says he appreciates how Fusto always seemed to know what to do in a crisis, a trait he hopes he can pass on to other nurses.

“There have been times when the tension starts to get really great, when all hell is breaking loose, when we have a lot of people hurt bad and there’s blood all over the place,” he says. “And he interjects something just right to lighten the mood, not anything disrespectful, but something to help everyone relax so mistakes aren’t made.

“I remember one time when things were really hairy. And you could cut the tension with a knife. And he said, with his tongue firmly in cheek, ‘Dr. Coates, I’m a nurse, so I know it’s my job to make you feel good. What can I do to make your life better?’

“The way he said it just made everyone laugh a little bit. It took the edge off so we could relax and do our jobs.”

Contact reporter Paul Harasim at pharasim@reviewjournal.com or 702-387-2908.