Churches need to refocus on the individual to attract the ‘nones’

![]() Churches seeking to recapture the growing numbers of religiously unaffiliated should forget about preserving the past and instead focus on the needs of those who see no need for organized religion, one mainline Protestant thought leader said.

Churches seeking to recapture the growing numbers of religiously unaffiliated should forget about preserving the past and instead focus on the needs of those who see no need for organized religion, one mainline Protestant thought leader said.

The Rev. Tom Ehrich, an Episcopal priest, church consultant and Religion News Service columnist, and other faith and thought leaders have been responding to whether and how the unaffiliated can be reached after a Pew Research Center study that found those who don’t identify with a particular faith, the so-called “nones,” have grown as much as some mainline Christian faiths have declined.

Ehrich said the take-away for him is a reminder that the bottom line for faith isn’t about buildings or budgets, but the people found inside and outside the walls.

“I think a lot of the concern over the Pew findings has to do with institutional survival,” he said. “They have to realize God probably doesn’t have a lot invested in that. God’s interested in people, not institutions. We’ve got to find a better reason for caring about this than meeting our budget next year.”

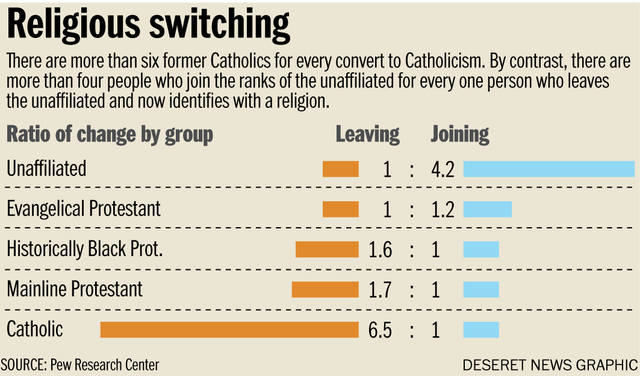

While the number of Americans who profess to be Christian has declined 7 percentage points in the past seven years, it still stands at 71 percent. But those who identify as religiously unaffiliated, which includes atheists, agnostics and those who are “spiritual-but-not-religious,” has increased from 16.1 percent to 23 percent in the same period, according to Pew researchers.

Washington Post columnist Michael Gerson saw the numbers indicating a “collapse of casual Christianity and of religious belief as a civic assumption,” while conservative Christians may see “a psychological adjustment is taking place.”

Not everyone believes the reported decline in Roman Catholic and mainline Protestant numbers is unique to this time, however. Church movements have gained and lost adherents during earlier historical periods. And, Ehrich said, some of the losses Pew noted may be part of a traditional pattern.

“There’s a fairly typical life cycle to faith,” he said. “People will, when they’re children, participate in the faith of their parents: they will go to church if the parents go, say grace if the parents say grace; it helps them count as part of the family. In adolescence, everything ebbs, to allow children to become an independent, autonomous individual.”

Lost generations

But faith leaders can’t wait for the sudden return of those who are not sitting in their pews.

Ehrich, who is based in New York City, said church leaders need to consider ways to meet the needs of newer generations. Today, he said, many congregations have become stuck in a rut accommodating older members.

“The average age (of members) in a mainline church is somewhere between 62 and 66; 20 years ago it was between 42 and 46,” Ehrich explained. “We’ve missed two successive generations of young adults, and the same people who stuck around are getting older. We can’t go on much longer before the 66-year-olds are 76 and 86. That’s why the (churches) are closing.”

A lack of connectedness also hampers church membership, said the Rev. Thomas Lambrecht, vice president and general manager of Good News, a United Methodist renewal movement headquartered near Dallas.

“People who are only marginally connected to the church — perhaps their name is only on a membership roll — aren’t seeing the value in that connection,” Lambrecht said. “I think what’s happening with the decline in mainline churches especially is the loss of the vitality of the gospel and the power of the Holy Spirit.”

The Rev. Dwight Longenecker, a Roman Catholic priest in Greenville, S.C., and a Patheos.com religion blogger, says the loss of the unaffiliated may stem from the relative ease many of the so-called “nones” have in their present lives.

“Usually people will turn to God when they have reached a crisis,” Longenecker said. “My own view of ‘nones’ is that they are comfortable without God and religion. Once they are uncomfortable enough, they will turn to God.”

But when those “nones” are “uncomfortable enough,” Ehrich wonders what kind of church they’ll find. If a congregation doesn’t operate with the 21s century in mind, he says there may be a disconnect.

“Churches that are growing have small groups, high mission activities, mission teams, lots of people engaging with each other, and digital dialogues,” he said. “The mainline churches and many churches are resisting it because people don’t want” those changes, preferring traditional routines.

He believes that many adults in their 30s and 40s who begin to investigate congregations will be newcomers. “There’s a lot of handwringing about ‘what we did to drive the young people away,’ (and) I say, you never had them to begin with,” Ehrich said.

Is Jesus missing?

Both Longenecker and Lambrecht say a reason for declining interest in mainline congregations is a lack of emphasis on traditional Christian faith.

Lambrecht says many of those claiming the “none” label are just making a “more honest” connection to their beliefs, “rather than pretending to be something that they’re not.”

“People aren’t ‘nones,’ they’re all people,” Longenecker added. “I don’t think of these categories at all. We preach the gospel and let the Holy Spirit do the rest no matter where a person is starting from.”

And, he said, it’s that preaching of the core Christian message that will draw seekers, regardless of their affiliation or non-affiliation.

Church consultant Ehrich said congregations also need to position themselves as providing answers to the questions those seekers eventually will bring.

“What the churches have to communicate is this is what they’re about and not keeping up tradition,” he said. “They’re not in the tradition business. We should be in the business of helping people discern God’s presence in their lives at the time they want to make that discernment.”

Strategic focus

All three faith leaders agreed that not only strategy but also mechanics need to be well-considered when responding to the needs of today’s and tomorrow’s seekers.

Ehrich says he tells the congregations with which he works to “go to the edge of your (church) property and face outward” into the community. Identify the problems people are facing, whether it’s loneliness, the decline of the middle class, or what he called “the collapse of public education.” Then, he added, churches should see what they can do to help address these problems.

At the same time, he said, those congregations should employ “good quality control” on a church’s physical plant and program: fix “rusted church signs,” be sure to have other signs showing where the restrooms are, and replace faded carpeting. Avoid “low-energy” Sunday School classes and eschew a “haphazard” approach to nursery care.

Lambrecht, whose organization’s motto is “Leading United Methodists to a Faithful Future,” said the stable numbers for evangelical affiliation should offer a clue about what mainline congregations need to do.

“One of the interesting findings (of the Pew survey) was the growing strength of the evangelical movement, points to a need for a recovery of orthodox doctrine and practice within the mainline church,” he said.But Longenecker cautioned against trying to fit traditional faith to current fashion. “History is littered with the shipwrecks of (church movements) that tried to adapt to this or that trend or this or that demographic group,” he said, declining to name specific organizations, “lest I offend.”