Family Promise pairs faith with hope

It’s about 5:30 p.m. and the late-summer heat is still simmering at around 100 degrees, making even the peaceful, tree-dotted courtyard at Christ the King Catholic Community feel like no place for the weary.

Just off the courtyard, inside a spacious, air-conditioned community room, three women are bustling back and forth between the kitchen and a long, rectangular serving table covered with a white cloth. One of them has an oven mitt on her hand, and wears a thin, white sweater and tiny diamond cross around her neck.

The women set out bowls of chopped lettuce and tomatoes, a foil casserole dish filled with steaming taco meat, serving spoons and flatware. Everything, even the lime-colored Gatorade, is placed just so.

A door opens, letting in the hazy evening sunlight, and a mom walks into the room with her five young children. Even after a long drive across town in the heat and the smell of supper in the air, the children, ages 3 to preteen, barely make a ripple as they follow their mother to a table and sit quietly.

A man and his 7-year-old daughter then enter, followed by a pregnant woman with two young boys, and another woman toting a car seat with an 8-month-old child tucked inside.

Mary Louise Sloan, the woman in the white sweater, greets the families warmly and enthusiastically, like a grandmother or favorite aunt. She asks what she can get them to drink, and dotes on the children with words such as “cutie pie” and “beautiful.”

Adults talk and laugh, toddlers fuss. At the edge of the room, a little girl weaves around the dining tables and chairs, happily chirping, “Tacos, tacos, tacos.”

For these families, all of them homeless, this place, at this moment, is sanctuary.

WELCOMING ATMOSPHERE

Every week, somewhere in the valley, a local congregation is opening its doors to house and feed homeless families that might otherwise have no place to go. Meeting rooms, libraries, parish halls and kitchens are transformed into makeshift overnight shelters run by congregants who volunteer their time.

The Interfaith Hospitality Network is the creation of Family Promise of Las Vegas. The nonprofit organization has been helping local families find permanent housing in the valley for the past two decades. By partnering with local congregations, it is able to provide temporary shelter while clients work on getting their lives back on track, according to Family Promise Executive Director Terry Ruth Lindemann.

There are 17 host congregations across the valley that take part in the program, sheltering as many as four families at a time on a rotating, week-by-week basis, as well as supporting congregations who supply food and volunteers.

The beauty of the network is that the host congregations make up a cross section of faiths, including Protestant, Islamic, Catholic, Jewish and Unitarian, Lindemann says. Woven into their nature, she adds, is the inherent desire to help those in need.

“Within these core faiths there are people who want to help their neighbor, so it was developing this program where Family Promise could say: ‘Hey, we have a way you can help your neighbor, and in your own building. You don’t have to get on a bus with your youth group and go down to a shelter, you can do it right there, we can train you,’ ” she says.

At the same time, the families receive a kind of “holistic” experience, she adds. Each week they venture into different parts of the valley and meet members of the community from all walks of life. The shelter program allows Family Promise to keep the families together and hone in on their specific needs.

“It gives us the time to work with the families, to hear what they think, to hear what didn’t work and be their guide, by their side. This is much more difficult when you’re helping hundreds at a time,” she says.

KEEPING FAMILIES TOGETHER

According to the 2014 Southern Nevada Homeless Census and Survey, there are 9,417 homeless people in Southern Nevada, an increase of 28 percent over 2013. The report notes that about 36,718 Southern Nevadans experienced homelessness at least once during the previous year.

The specific number of homeless families is not available, but Lindemann says that about 90 percent of the families in her program are from Clark County. Their circumstances are a result of issues such as unemployment, the breakup of a family or the financial strain of a medical crisis “where they lost everything,” she says.

The interfaith network, which can shelter families for as long as three months, provides about $300,000 annually in terms of donated volunteer hours, meals and shelter, she adds.

Tim Burch, director of the Clark County Social Service Department, emphasizes that in many cases local homeless families are not able to remain intact because of the nature of the services that are available, including shelters that only cater to women and children, or homeless men.

“A lot of families will stick together and either live in a car, on the streets or some other thing because they don’t want to split up,” he says.

The Interfaith Hospitality Network is “critical” because it not only allows families to stay together but gives them the chance to find permanent housing as quickly as possible, Burch says. What is known in social-services vernacular as “rapid rehousing” is, in fact, the most effective way to get families stabilized and out of the homeless stream, he says.

As far as the specific nature of the program, families are taken to a host congregation every evening, where they receive a hot meal and put together sack lunches for the following day.

The parents and children then spend the night on air mattresses set up in different rooms, eat breakfast the next morning and are then taken back to the Family Promise office in downtown Las Vegas.

During the day, parents look for work, and connect with various agencies and services, while the children are in day care or go to school.

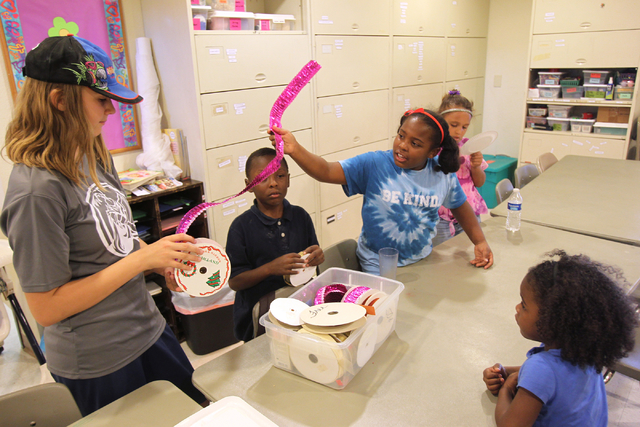

Volunteers at the congregations perform duties that range from cooking and washing dishes, to spending the night. They are also encouraged to interact with the families by sitting down with them at dinner, for example, or organizing games for the children.

The idea is not to proselytize or ask too many questions, Lindemann says, but be a warm and welcoming presence. Often, it is just a matter of listening.

MUTUAL BENEFITS

Angela Anderson started working as a volunteer for the shelter program at her parish, Grace in the Desert Episcopal, four years ago. She is now the church’s volunteer coordinator.

Initially, she joined because of a compassion for the homeless and as a way to put her faith into practice. But the program has opened her eyes in ways that wouldn’t have been possible had she never signed on, had she kept her distance.

Anderson says she has been surprised by the number of single dads in the program, and the men and women with college degrees struggling to find work.

“These are people just the same as we are and you get the feeling that but for the grace of God go I. There’s a fine line sometimes, you know? … There are lots of good programs and projects out there, but you never actually see what you’re doing being put into action, and that is one thing with this program, it’s hands on. You see the people,” she says.

Outside the community room at Christ the King, it is finally cooling down. The taco dinner is over and some of the families are resting in the courtyard, others make their way to the meeting rooms where they will sleep for the night.

One volunteer, Laura Alvarado, takes a short break and sits down at a table in the community room. She talks about her volunteer work as a “two-way blessing.” The families keep her grounded, she says, especially the children.

“You cannot just see these families and not feel tenderness and, like I say, the pouring out of your heart, hoping they will get something, they’ll get a break,” says the 41-year-old, who has been volunteering for about eight years.

Sitting next to her is Solangel Baluarte, another volunteer. Baluarte, who is 44, explains that she was once homeless herself, losing everything during Hurricane Katrina in 2005.

A Methodist church in Alabama gave her food and shelter for nearly two months, she says, before she moved to Las Vegas and finally found work.

As the women go back to the kitchen to clean up, Tyler, a 30-year-old single dad and his daughter have finished dinner and are about to leave, when the little girl bumps her knee on one of the dining chairs, and starts to cry.

He picks her up and holds her, and eventually the tears stop. But the 7-year-old, her hair pulled back in a long ponytail, doesn’t seem to want him to let her go.

Tyler talks about losing his home and, as a result, having to give his daughter up to foster care. He was only able to get her back, he says, after getting into Family Promise because it provides a stable living situation. They were separated for three months, he says.

“I really appreciate the fact that (the congregations) are helping us out like this. I couldn’t ask for a better place to have my child at. We were in a pretty bad situation before.”

He chuckles and says that last week his daughter asked if the church they were staying at could be their permanent home.

“The people have just been awesome, really nice, really pleasant … we couldn’t ask for nicer people,” he says.