Millennials favor doing good over divinity

Editor’s note: This is the second of a two-part series on Millennials and religion.

Can you talk the talk and walk the walk but not pray the prayer?

Increasingly, one generation is adopting that ethos.

“After discussing it with my friends, I believe there is no higher power,” says 23-year-old Andrianna Moore, an AmeriCorps volunteer in Reno. “We just need to make our planet a better place.”

Depending on how much stock you place in studies, surveys, statistics and reports measuring religious and social trends, you might be alarmed, encouraged or just have your antenna up regarding the generation known as the Millennials — those born, more or less, between the late 1970s and early 1980s. (Sociologists can’t agree on the exact age span, with some sources citing as many as 20 ranges.)

Overall conclusion: Millennials, who comprise approximately 24 percent of the U.S. population, are less inclined to practice religion and more inclined to practice volunteerism and altruism — ironically, a cornerstone of most religious doctrine — than their parents or grandparents.

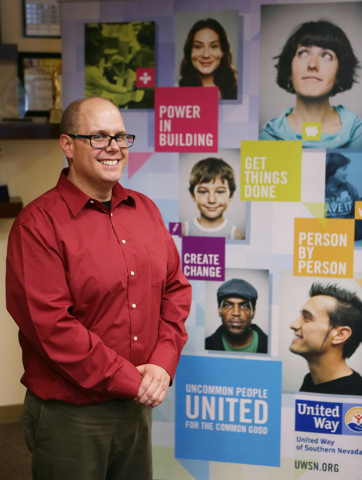

“Through personal discovery, I realized I wasn’t concerned with whether or not there was a higher power; it didn’t affect my day to day life,” says 34-year-old Las Vegan Jacob Murdock, community engagement manager of United Way of Southern Nevada who was raised Protestant but now considers himself agnostic. “But when I think about why I volunteer, I think of the golden rule. I still feel you do unto others as you would have them do unto you.”

Last week in this space, local religious leaders, a UNLV sociology professor and a leader of the Las Vegas atheist community weighed in on these twin trends.

As a refresher: In 2012, a Pew Research Center study found that nearly a third of Millennials refuse to identify themselves as belonging to any organized religion, more than Generation X, the baby boomers and the World War II generation at the same point in their lives.

While that study was secular-based, the American Bible Society in its “State of the Bible” survey in April found that percentagewise, compared with adults overall, Millennials are less likely to: consider the Bible sacred literature (64 percent versus 79 percent); believe “the Bible contains everything a person needs to know to lead a meaningful life” (35 percent versus 50 percent); or even read the Bible (26 percent versus 39 percent).

“There are more and more Millennials in our group,” says Brian Naldoza, 36, of Las Vegas, who hosts a local atheist Meetup Group. “When I first joined the group, it tended to be an older crowd. But they can see people standing together, identifying as atheist and agnostic. It normalizes nonreligiousness so people are less and less afraid of identifying as such.”

Parallel to the religion findings, a Nielsen Co. report in January says the Millennials did more volunteer work in 2013 than any other generation and is very civically engaged.

“The largest group of volunteers we have is Millennials 18 to 35,” Murdock says about the local United Way. Adds Naldoza: “They don’t need religion to identify what they call injustice and want to do something about it.”

None of this necessarily means America is looking at a godless future — the majority of Millennials, more than two-thirds, still identify as part of one religion or another. And we might even be headed for a more compassionate future.

But it does raise a simple question: Why?

“People act in different ways than what they are taught,” says Sophia Moreira, a 20-year-old UNLV student. “They preach unity and tolerance and acceptance of your neighbor for who they are. But when I post something about a church that supported gay rights, people from my mother’s church attack me for that viewpoint.”

Rigid positions on social issues, experts say, contribute to religion becoming off-putting to Millennials, whose views, Murdock says, arise more from generational solidarity than political differences. “Millennials support things like gay marriage regardless of whether they’re conservative or liberal or Democrat and Republican,” he says, and Naldoza links that to replacing ideology with experience.

“When you get more familiar with people in the LGBT community, you realize there’s no reason to discriminate against them,” Naldoza says. “They can humanize the group better than the religious right does.”

Raised as a “nondenominational” Christian, Moreira says that at age 13 she no longer wanted to be a follower. “I was able to see the effects it had on family and personal interaction and I decided for myself what I thought was best,” says Moreira, who is a philosophy major. “I read a lot of philosophy books, and reading outside of the religious world has really opened my eyes. I see more people in college who are really questioning those beliefs.”

In fact, a study in April, conducted at Massachusetts’ Olin College of Engineering, concluded that three factors — an increase in college-level education as well as a decrease in religious upbringing and the ubiquity of the Internet — explain about 50 percent of the drop in religious affiliation. And of that, 20 percent can be pegged to online activity, providing access to a variety of viewpoints that weakens the influence of religious dogma.

“People have more open minds in our generation, and they’re thinking about other possibilities,” says Moore, who stopped calling herself a Catholic six months ago after joining AmeriCorps. She had been president of the University of Nevada, Reno chapter of the Christian ministry Young Life.

“One person I know said he was very scared of going to hell because that’s what his mom told him his whole life. But after he started researching, he said, ‘How is that even possible?’ Our generation wants answers, not just believing what everyone else believes.”

Though baptized and raised Catholic, Naldoza traces his skepticism and eventual break with the church to hearing the story of Noah and the Ark.

“Even my 5-year-old brain was like, ‘That’s not possible,’ ” he says.

“From then on, I thought, maybe there will be a time when all this feels right, so I’ll just go along with it.” By the time he reached college — and took a philosophy course — he gave in to his doubts and severed his ties. Even interpreting the Bible stories as metaphorical, rather than literal, did not square with his new worldview.

“When a fig tree is disobeying Jesus (Mark 11:12-25), I don’t understand the metaphor, that’s where it falls apart for me,” Naldoza says. “My morality is informed by my experiences and my empathy. I really don’t need those stories if I’ve got my own understanding of what it means to be a good person.”