Stillpoint offers a place to turn down the noise

Do you have the will to be … still? Or does that ask too much in a tweeting/texting/Instagramming/ever-yammering world?

“Stillpoint is about a different kind of prayer,” says Delise Sartini, president of the aptly named Stillpoint Center for Spiritual Development at 8072 W. Sahara Ave. “It’s a prayer of contemplation and discernment, taking the time to discern, Where is God in your life?”

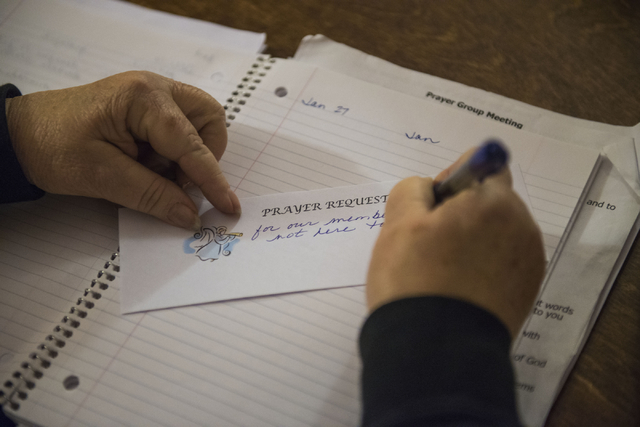

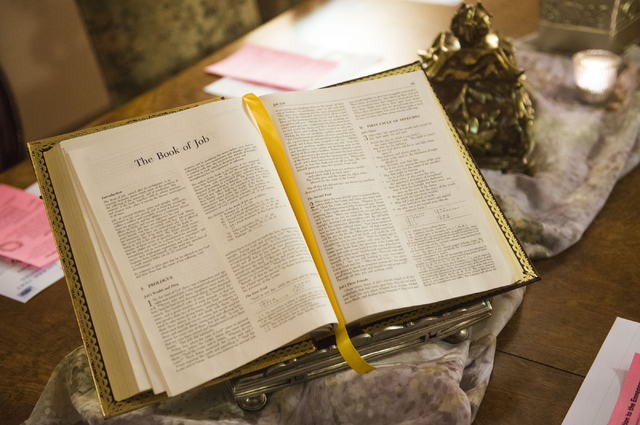

On this day, practitioners — there are no “members,” nor congregants because this is no church — convene for Lectio Divina (Latin for “divine reading”). Though the Benedictine practice requires gatherers to read Scriptural passages, it eschews literal and theological interpretation in favor of savoring them through meditation and contemplation.

Spirituality — not religiosity — is the goal.

“It’s a much broader prayer than what I was taught in my Catholic upbringing,” Sartini says. “We don’t eat the same foods we did when we were little, we don’t wear the same clothes we did when we were little, but so many of us still pray the way we did when we were little. This is a more adult form of prayer.”

Those of all faiths — and no faiths — are welcome at Stillpoint, which recently celebrated its 10th anniversary of tending to spiritual seekers in Las Vegas. Multiple programs, retreats, guest speakers and, particularly, regular “centering prayers” are among the activities encouraging a part of ourselves that many people casually claim — does “I’m not religious, but I feel very spiritual” sound familiar? — but do little to nourish.

“I went to get a haircut and I told the girl cutting my hair what I do, and I think she went 20 minutes without touching my hair , she was really going on about her spirituality, so there really is a hunger out there,” says Brian Neely, who was a Baptist pastor before shifting to Catholicism in 2006. Neely, who assumed Stillpoint’s executive director post about six months ago, notes that sometimes houses of worship are hampered in guiding congregants down spiritual paths.

“Sometimes churches will get so big that a pastor becomes the CEO just to make the machine function,” Neely says. “They are sometimes not able to provide the spiritual care people are desiring. We’ve been able to tap into that at Stillpoint.”

Adhering to the motto “Be Still and Know That I am God,” Stillpoint was created in 2004 by a group of Roman Catholic women headed by founding director Roison O’Loughlin, and it is overseen by a multidenominational board of trustees. “The traditional monasteries and nunneries are closing down because it’s hard for people in this day and age to get away for a weekend (for retreats),” Sartini says.

“The new idea was creating retreat centers in the heart of busy cities where people could come for an afternoon on their lunch break to be able to access spirituality in the midst of their busy lives. We are the only one like this in the United States not affiliated with a specific parish or religious group, that is just a day center.”

Events are scheduled almost daily. Using Buddhist meditation principles, centering prayer focuses on silence and listening. Led by a clinical psychologist, “mindfulness-based stress reduction” sessions use methods including tai chi and breathing techniques to quiet the noise of everyday life.

In another form of meditation, Tibetan crystal singing bowls creating harmonic overtones are used with yoga, and a series called “spirituality and health,” helmed by a physician, enumerates meditation’s medical benefits.

“By doing meditation and being quiet, all of a sudden a light will come on, and it’s a grace coming from God,” practitioner Larry Ishum says. “We have such a great interconnected feeling.”

Among discussion-based programs: A dream group employs Jungian principles to analyze their cryptic meanings; a sacred text series is geared toward what Neely calls “pulling universal truths” out of different religious texts to uncover their spiritual elements; a reading group selects books featuring allegories or fiction tethered to spiritual themes, such as Mitch Albom’s “The Timekeeper,” Edward Hays’ “In Pursuit of the Great White Rabbit” and Joyce Rupp’s “Walk in a Relaxed Manner”; and the “Abrahamic Faith” series studies the three major religions — Judaism, Christianity and Islam — that trace their roots to the biblical figure Abraham.

“There is so much going on, but sometimes I’ll just see someone sitting with a cup of tea reading a book in the library, or there’s someone in the meditation room who just stopped in to pray for a little while,” Neely says. “And we’re a safe place. They don’t have to worry that they will say a doctrinal thing wrong.”

In the center’s Enneagram program, attendees analyze the ancient theory that there are nine patterns of the human personality, the goal being to eliminate repetitive behavioral loops that block communion with God. Also on the schedule are “Desert Days” retreats; workshops on cultural traditions, such as Native American ceremonies; and guest speakers, including Holocaust survivors, Islamic leaders and authors. (The next is Diana Butler Bass, author of “Christianity After Religion: The End of Church and the Birth of a New Spiritual Awakening,” on March 7).

Local religious leaders regularly appear at Stillpoint, given its open-door policy toward all faiths. “A Hindu priest came into one of our programs and he said, ‘There’s many paths to the top of the mountain, but only one view from the top,’ ” Sartini says. “That is the oneness of us all, our desire for a relationship with God, Allah, The Holy One, Yahweh, the Divine One, whatever you want to call him.”

Yet religion and spirituality don’t always meet in perfect symmetry.

“There is a place for religion because it’s the container that you hold your spirituality in,” Sartini says. “But I think there are people who have been hurt by religion, so they run away from their religion of origin. They still have that spiritual component, but they’re looking for something else.”

Compatibility between the two depends on whom you ask. “I stopped going to church because in church they’re teaching rules and regulations, following the Ten Commandments and all that stuff,” Ishum says. “But in spirituality, the whole name of the game is to learn how to love God above everything, and how to be silent in God’s presence.”

Ask practitioners Katrina Steiner and Jan Hill, however, and houses of worship and Stillpoint hold hands in harmony. “To me, they’re one and the same,” Steiner says. “I go to church every week, sometimes every day. One just adds another layer to the other.”

Adds Hill: “I’m not a churchgoer, and I was worried when I first came because I thought it might be too much based on religious tradition, but I found it’s not. It’s very complementary to whatever your religious beliefs are. We can express different viewpoints, but we all have that common search for connection.”

By offering a big-tent approach to spirituality, Neely says he wants Stillpoint’s programs to send Christians, Jews, Muslims and believers of any religious stripe back to their churches, synagogues or mosques as better practitioners of their own faiths.

“But when people come and they’ve left behind a religion, I think we can help them as well,” Neely says. “We can provide opportunities to continue to explore who they are.”

Just bring the will to be … still.