Why do we believe apocalypse predictions?

So where were you when the apocalypse fizzled?

Actually, make that apocalypses, because the past few weeks have been (pardon the word) heaven for fans and followers of doomsday predictions.

First came the prediction, based on a book by a Mormon author, that possibly pre-apocalyptic events would take place during September. Then came a separate prediction from an evangelical Christian group that pegged Oct. 7 as the day when Earth would be destroyed.

Of course, neither prediction panned out — we're still here, right? — and we're left with that usual hangover of equal parts amusement, relief and vague disappointment that seems to follow every failed doomsday.

Be it countless predictions of the Second Coming, Heaven's Gate, Y2K, the Mayan calendar, or some as-yet-unspecified pandemic, natural or extraterrestrial disaster, humans have been finding ways for the world to end for roughly forever, and we'll probably keep doing it until one of these things actually happens.

Even if the scorecard right now still has the doomsayers batting oh-for-infinity.

For this most recent spate of apocalyptic thinking, we go, first, to a combination of things — including that recent blood moon and fluctuations in the stock market — that some interpreted as signaling a procession of possible pre-apocalyptic events. News reports noted that the predictions, linked in part to books by author Julie Rowe, prompted significant sales increases of emergency supplies in parts of Utah.

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, while noting that Rowe is a church member, was moved to issue a statement that Rowe's book is not endorsed by the church and that the experiences she recorded in it don't necessarily reflect, and may distort, church doctrine.

More recently, the founder of E Bible Fellowship, a Pennsylvania-based Christian group, predicted that there was a "strong likelihood" that the world would end on Oct. 7. It didn't.

Kevin Rafferty, a College of Southern Nevada professor who teaches the anthropology of religion, calls apocalypse "one of the deepest and longest-held motifs or ideas in civilization."

"It crops up on a fairly regular basis," Rafferty says. "About 1000 A.D., at the millennium, everybody thought God was coming back, and at least in Western Europe, there were crowds of flagellants wandering Europe, atoning for the sins of mankind, hoping God would forgive everybody."

Many apocalyptic scenarios throughout history have grown out of religious revelation or interpretations of religion texts. In the Christian tradition, for example, "apocalypse literature was first written around the first century," says Bishop Dan Edwards of the Episcopal Diocese of Nevada.

Apocalyptic literature also is "essentially encoded," Edwards says. "I think that's part of the attractive mystery to it, that it's actually written in an encoded way, and it's written in an encoded way because it is intensely and specifically political. It's written in opposition to some kind of imperial power."

Take the Christian Bible's Book of Revelation, which has provided the foundation for numerous apocalyptic scenarios in both religion and popular culture. While many Christians take the book literally and regard it as a chronicle of times to come, other Christians don't.

Revelation "is written as a political diatribe against the Roman Empire," Edwards says, and "is not literally about, quote, the end of the world. It was about the overturning of existing political power structures. So the use to which we have put the apocalyptic literature is way, way different from the intention of the people who wrote it and the way the first people who read it would have understood."

Apocalyptic literature also "has fallen in and out of favor through history," Edwards adds. "We have not always been obsessed with apocalyptic literature, and we have, occasionally, increased spasms of anxiety, of becoming obsessed with it."

A preoccupation with the end times typically arises during times of societal, political or economic upheaval, Edwards notes. Take the Middle Ages, a time of plague and "a lot of shifting of power structures and economic unrest and turmoil," Edwards says. "So when the foundations of our world as we know it seem to be shaking, we are drawn to this apocalyptic literature and interpret it as prophesying the end of the world or some specific age."

Doomsday doesn't stem only from religion. Consider "all the doomsday scenarios in movies," Rafferty says. "The 'Terminator' series is, perhaps, the most recent example of this secular approach to apocalypse or doomsday, and that fear that things are out of control and there isn't anything we can do about them. And we kind of express those fears through our art and our storytelling."

But make no mistake: Fear is essential to slipping into a doomsday state of mind. The fear "may not be at the top of your mind or your emotions, but fear is always there at some level," Rafferty says.

"I think the world is, for an ordinary human being, kind of a mysterious, uncontrollable place," Rafferty explains, and as much as we like to think we're in control, "as soon as things start going wrong, our fears of being out of control kind of come to the fore, and this kind of apocalyptic thinking is kind of the expression of this fear being out of control."

"Hope springs eternal, but so does fear," notes Joe Nickell, senior research fellow for the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry, which publishes the magazine "The Skeptical Inquirer," and the ways in which we react to our fear may prompt us to accept things that others might find a bit odd.

"You wonder why on Earth do people believe in X or Y, and a lot of it has to do with, we respond to a lot of things with our emotions and then we try to get our brain in gear," Nickell says. "And, sometimes, having decided on the basis of our emotions that something is good or bad, we then justify that feeling by logical reasons, or we'll cite a holy text."

"It's what's called conformation bias," Nickell says, "where you start with the answer and work backward to the evidence."

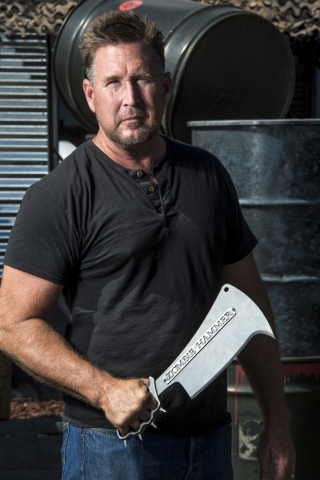

News reports noted that survival equipment stores in parts of Utah noticed sales increases that apparently were linked with the Rowe predictions. But Mike Monko, president of Zombie Apocalypse Inc., which runs the Zombie Apocalypse Store at 3420 Spring Mountain Road, says he saw nothing out of the ordinary here.

In fact, Monko has noticed that sales spikes are more likely to be prompted by political elections than fears of some uncertain disaster. He suspects that, for some, political leadership changes can evoke fears of scary changes to come.

But, even then, it's still about fear, Monko says, and that fear "is always there. It's under a slight fog, just barely veiled, and when an election comes around, it peeks up through the top and people see the potential for fill-in-the-blank or see it as evidence of fill-in-the-blank."

Contact reporter John Przybys at jprzybys@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0280 or follow @JJPrzybys on Twitter.