COLLIERVILLE, Tenn.

There were times when her son’s brain was on fire, when he thrashed in bed, calling out in agony, that Kay McClure nearly lost her religion, questioning her faith in God.

Because if he was truly benevolent, she recalled thinking, why on Earth wasn’t he stopping this?

For seven long years, Grayson McClure languished in bed inside a cramped Reno apartment, in the grips of a mysterious illness that produced round-the-clock seizures that no doctor or medicine could control. The convulsions were so violent that her son’s toes curled and his shoulder popped out of its socket. It was during that time that the Review-Journal first chronicled their story in 2016.

Kay McClure holds a pair of oral sprays used by her son, Grayson, at their home in Collierville, Tenn., in April. (Chase Stevens/Las Vegas Review-Journal)

Kay McClure holds a pair of oral sprays used by her son, Grayson, at their home in Collierville, Tenn., in April. (Chase Stevens/Las Vegas Review-Journal)Kay, a 61-year-old with a lilting Tennessee drawl, did what mothers do: She never left her son’s side. She injected powerful medicine into the port in his chest whenever the demons came. In those precious few hours she slept, she dreamed of tending to him.

She scoured the internet for answers, called more experts, did everything she could.

But eventually, she stopped praying.

“I’d prayed for so long,” she said in an interview last month. “But I wasn’t being heard.”

Since 2005, the pair had embarked on a desperate search for anybody who could stop the seizures that had hot-wired Grayson’s brain. They saw neurologists; endocrinologists; experts in chronic fatigue, metabolic issues, neuromuscular and nervous disorders.

They were eventually rejected by a half-dozen major medical centers associated with the National Institutes of Health’s Undiagnosed Diseases Network, with most experts throwing up their hands.

Then, in 2011, Kay found a pair of physicians who operate the Sierra Integrative Medical Center in Reno — the first doctors with a plausible explanation of the illness that had befallen Grayson.

Years later, the long night finally turned into day.

Now 26, Grayson has experienced a remarkable breakthrough in recent months, thanks in part to an electromagnetic brain procedure previously used on depressed patients.

Doctors also credit Kay for helping trigger her son’s improvement with a sublingual spray she found on the internet. The organic treatment calmed Grayson’s brain just enough that he could leave bed for the first time in years — and be wheeled across the street to the doctor’s office for continuing treatment.

Grayson’s story is one of a young man’s unshakable spirit to cope with unimaginable pain. But it’s also a tale of a mother’s stubborn search for answers. And it’s about a father, Terry McClure, who held down the family home, alone, waiting for his son to become well, for his wife and son to return, and for his family to become whole again.

If you believe in such things then, well, this has been a miracle. A year ago, many people, including us, we were just waiting for Grayson to die. Now he’s back home.

RICHARD POWELL, neurologist

The young man’s recovery is far from complete. His memory remains foggy, his body as frail as that of a man three times his age. There’s also the issue of a past unlived — the rites of passage he missed while lying in bed for more than half his life.

Grayson never went to high school or attended senior prom, never kissed a girl or fell in love or had his heart broken. He’s never driven a car or held a job. His parents still give him an allowance. He’s had few relationships with people his own age, instead sharing time with doctors, nurses, therapists and, of course, his own mother.

Kay always told her son that he wasn’t living on the world’s time, but on Grayson’s time. “I know I missed things, but I can’t change that,” he said. “Now I’m just trying to be me.”

His doctors remain stunned by his turnaround.

“If you believe in such things then, well, this has been a miracle,” said Richard Powell, a neurologist specializing in neuro-cognitive rehabilitation and pain management, who treated Grayson. “A year ago, many people, including us, we were just waiting for Grayson to die. Now he’s back home.”

Grayson McClure, left, stands with his mom, Kay McClure, and service dog Yojimbo, at the park at Town Square in Collierville, Tenn., in April. (Chase Stevens/Las Vegas Review-Journal)

Grayson McClure, left, stands with his mom, Kay McClure, and service dog Yojimbo, at the park at Town Square in Collierville, Tenn., in April. (Chase Stevens/Las Vegas Review-Journal) ‘My brain is on fire’

In 2005, the youngest of Terry and Kay McClure’s three children was running the basketball court at practice when his face suddenly flushed.

The 12-year-old called to his father, the coach, “My brain is on fire!”

The brain storms became so frequent that Grayson required a wheelchair. Eventually, Kay was forced to take him out of school and quit her job as a teacher.

Together, they embarked on a medical crusade to put a face on this undiagnosed disease, visiting the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, and research centers in Maryland, in Texas and at Tennessee’s Vanderbilt University. None could help.

Grayson was eventually diagnosed with Lyme disease, but the medication sent him into convulsions, which came one after the other, like wave sets at a beach.

Kay McClure administers medicine to her son Grayson in their Reno home in 2016. (Cathleen Allison/Las Vegas Review-Journal)

Kay McClure administers medicine to her son Grayson in their Reno home in 2016. (Cathleen Allison/Las Vegas Review-Journal)“I just tried to survive each day,” he recalled. “When one attack subsided, I’d have a few moments to catch my breath before another one hit.”

Then Kay found Bruce Fong, an internal and integrative medical specialist who had treated Lyme patients. Mother and son immediately moved to Reno, where life became a two-actor tragedy, staged in a tiny apartment bedroom. Kay kept the lights low and the temperature at 55 degrees to help calm her son’s sensitivities, flinching when the convulsions came, when he “wailed like a woman in labor.”

But Kay stayed put: “You keep trying. You do anything you can. It’s horrible.”

With Grayson so immobilized, doctors came to him, frustrated they could not do more. They could not map Grayson’s brain, knowing he’d convulse during the procedure.

But time was running out.

“It got to the point where it became difficult to stomach,” said Powell, “standing by his bed in that little prison and not being able to figure something out.”

Doctors also worried about Kay. “We also tried desperately to manage her care,” Powell said. “We worried she was going to suffer a major breakdown.”

Promising sign

Kay found the puzzle’s first answer in late 2017: an online supplement that promised to boost her son’s immune system and remove body toxins.

Medication on the bedside table of Grayson McClure at his home. (Chase Stevens/Las Vegas Review-Journal)

Medication on the bedside table of Grayson McClure at his home. (Chase Stevens/Las Vegas Review-Journal) Before spraying the organic medicine beneath Grayson’s tongue, she hesitated. “Please don’t let this backfire,” she whispered.

Within minutes, Grayson was asleep. “No, this can’t be,” Kay said.

In April 2018, doctors also removed an infected port in Grayson’s chest. The device had been in place for six years.

“We were going to remove the site where he got his medicine,” Kay recalled. “There’d be no more of the IV meds that had been the only thing relieving those tremors.”

Grayson also realized the stakes. “It was a truth-or-die moment,” he said.

But it worked.

Weeks later, as Grayson’s condition improved, he was finally wheeled into Fong’s office for a brain scan, where he collapsed to the floor, convulsing.

When his body finally calmed, doctors scanned Grayson’s brain, the results showing excessive activity in the area responsible for muscle control. “We’d suspected it,” Powell said. “But we finally confirmed it.”

Fong suspects a possible cause of Grayson’s illness is what he calls “a perfect storm of Lyme disease, hormones from puberty and genetic deficiencies.”

Doctors devised a treatment plan — using repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation, or rTMS, a therapy normally used to relieve depression and anxiety. But instead of targeting the entire cerebral cortex with high-frequency impulses, doctors used a lower setting, aimed at a specific area, to slowly lull the rapid-fire synapses in Grayson’s brain.

“Most doctors use a shotgun approach; we were more like snipers,” Fong said. “Those non-invasive brain stimulations made all the difference in the world.”

Physical therapist Walker Gardner, left, examines Grayson McClure at EXOS Physical Therapy & Sports Medicine in Collierville, Tenn., in April. (Chase Stevens/Las Vegas Review-Journal)

Physical therapist Walker Gardner, left, examines Grayson McClure at EXOS Physical Therapy & Sports Medicine in Collierville, Tenn., in April. (Chase Stevens/Las Vegas Review-Journal) Grayson was soon walking into the clinic, often chatting with staff.

“There was no hyperactivity in his brain,” Powell said. “None.”

Added Fong: “We fixed the tripwire to his seizures. He was caught in a loop, and we finally broke the cycle.”

Success came from the effort of not only the doctors — but also a mother.

“There wasn’t one magic therapy,” said Powell. “We tried things. Kay tried things. And we finally found the right recipe.”

The physicians will continue to explore the use of rTMS as a solution to Lyme disease-related convulsions. “We’re not done with this case,” Powell said.

This spring, even as Grayson got better, Kay worried about taking him home.

The band Weezer settled all that.

Grayson’s favorite group was coming to Memphis for a March concert. His sister, Lauren, offered to get them seats in a luxury suite.

“Mom, I’m going to that concert,” he said.

Kay said, “OK, let’s try.”

Terry, an engineer at a construction firm, revealed that his company had contracted a private jet for the trip. On the day of the show, the family flew home.

Once there, Grayson rushed to the concert while Terry waited in the car outside with medication and muscle relaxers in case of a setback. Kay stayed home and worried.

For a young man who’d lived life in a bubble, the concert was like exploding the balloon. When the music started, Grayson and his older sister both broke into smiles.

“I told her that the vibrations and lights normally would have made me seize,” Grayson recalled. “But not now. I was coping.”

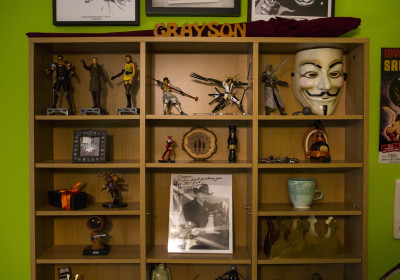

Personal items in the bedroom of Grayson McClure, including a signed message and picture from actor Chuck Norris. (Chase Stevens/Las Vegas Review-Journal)

Personal items in the bedroom of Grayson McClure, including a signed message and picture from actor Chuck Norris. (Chase Stevens/Las Vegas Review-Journal)Fighting pain with humor

Grayson’s bedroom remains a preteen’s time capsule, its shelves lined with movie action figures, Japanese anime, movies, video games and comics.

Yet his most prized possession comes from his darkest days.

When he landed in Reno, he was housed full time at Fong’s clinic, where he befriended a man suffering from tremors. Kay called them the “seizing soul brothers.”

The two wielded humor to cope with their pain. The other patient, who uses the initials J.R., produced a cardboard Burger King crown someone had left behind as the prize for an odd contest: Whoever had the most seizures won the crown.

One day, Grayson was wracked by so many convulsions J.R. declared him the victor. He still keeps his precious crown and the framed card his roommate gave him.

“To the King,” the envelope reads. The words still make him smile.

I don’t know what caused it. I don’t know what fixed it, and I’m OK with that. I’m just ready to be done with it.

GRAYSON MCCLURE

With each passing day, Grayson becomes more comfortable in his own skin. He’s contemplating going back to school to became a forensic psychologist and even went on a date recently. He now takes methadone to guard against further attacks.

His condition is finally under control. “I don’t know what caused it. I don’t know what fixed it, and I’m OK with that,” he said. “I’m just ready to be done with it.”

Since her return home, Kay has slept a lot, still exhausted, like a medical refugee returned home from war. But she’s overjoyed to see her son out of pain. “I’m happy,” she said. “I’m overwhelmed. I’m a nut. I’m a crazy woman.”

Still, she hovers over Grayson – often to his irritation. Every day, he yearns for a bit more independence. She calls him a walking miracle, and he just shrugs.

One afternoon, Fong telephoned for an update. He calls Grayson “G.”

Mother and son were at the kitchen table, Grayson’s glasses sitting askew. His dog, Yojimbo, a Labradoodle whose name means bodyguard in Japanese and who often sat on Grayson’s legs during his seizures, perched nearby.

Grayson McClure, right, shares a laugh with his parents, Kay McClure, left, and Terry McClure, at their home in Collierville, Tenn., in April. (Chase Stevens/Las Vegas Review-Journal)

Grayson McClure, right, shares a laugh with his parents, Kay McClure, left, and Terry McClure, at their home in Collierville, Tenn., in April. (Chase Stevens/Las Vegas Review-Journal) On a shelf sat a mammoth glass jar full of change that Terry collected for the entire time they were gone, as a measure of a family interrupted. Kay anticipated the day they all could sit down and count the change together.

Since her arrival home, she has sent Fong care packages of Memphis barbecue, a sign she has returned to embrace her old Southern life.

“I’m proud of you,” the doctor said that day. “Both of you.”

To just be happy

Then tragedy struck: Terry died a few days later, the 66-year-old collapsing during a weekend bike ride with a friend.

Together again so briefly, the family had yet again been torn apart.

Grayson is trying to accept the absence of a building engineer father who took him along to job sites so he could leave boyish handprints in the wet concrete of a new church.

“Dad’s mission was to get me and my mother home, and he completed that,” he said. “He was the happiest he’d been in his entire life.”

As Kay waited to bury the partner she met on a blind date, she recalled how she quickly fell for his subtle patience and simple life philosophy: to just be happy.

“I can’t tell you how many times we sat out on the back swing, and he turned to me and said, ‘I’m just so glad ya’ll are home.’”

John M. Glionna, a former Los Angeles Times staff writer, may be reached at john.glionna@gmail.com.