CCSD students, teachers face hurdles as 2022-23 school year begins

Terri Rupp chose to homeschool her son when he wasn’t thriving with the online distance learning the Clark County School District implemented for students in response to the early spread of COVID-19.

He will return to public school as classes start on Monday, but Rupp said she’s lost confidence in the district on the heels of a year marked by concerns over school safety, a national teacher shortage and dysfunction on the school board.

“Our district is so far gone in lacking communication. … I feel like there must be a drastic overhaul and just reprioritizing of what is important,” she said. “Our kids’ education should be more important than other things.”

Some issues, such as declining enrollment and teacher shortages, aren’t unique to the district, but others, including an escalation in violence on school campuses, have forced officials to step in and take emergency action over the last several months.

Rupp acknowledged that there are similar issues affecting school districts across the country, but she described the current situation in Clark County as one that has been compounding in a pressure cooker.

“I have to just continue being more engaged and involved with my kids to make sure I fill in that gap,” she said.

‘Wake-up call’ for school safety

Estrella Gomez, a 16-year-old junior, will start the fall semester at a new school — her third one since she started high school.

She’s transferring to Las Vegas High School from Eldorado High School, where a teacher was brutally attacked and sexually assaulted in April.

But Gomez said she had concerns with Eldorado before the assault.

“A lot of teachers don’t believe in you. That does a thing to a kid,” she said. “I think the incident that happened in April really did cement my decision of: I’m not coming here next year.”

Eldorado wasn’t the only school to see violence on campus this year. As fights erupted at several valley schools in the spring, the district implemented new disciplinary actions and began the process of reconfiguring schools around one point of entry.

Violence at Desert Oasis High School put the school into lockdown for two days in March. That disruption had a ripple effect on Rupp’s family: Her daughter attends nearby Tarkanian Middle School and arrived home an hour later than usual because of delayed bus routes.

Rupp said it was frustrating that parents weren’t notified of the changes.

“It was just a sad reality of: This is where our kids are growing up,” she said. “This is just another reason that we have to be involved, proactive parents.”

School police Lt. Bryan Zink said the violence during the last school year was the most he had seen in his 19 years with the district.

As students and staff return to classes Monday, they’ll see new fencing, upgraded cameras on buses and increased police presence at schools, according to district officials.

The district already has authorized $26.3 million for emergency security upgrades at Eldorado High School and $99,970 in upgrades for Clark High School. At the Aug. 11 board meeting — the first meeting of the school year — it also will recommend that an instant alert system it has piloted at several valley high schools be implemented throughout the entire school community.

For Superintendent Jesus Jara, the recent violence is indicative of violence in the community that’s spilling into schools.

“I think that as a school superintendent and as a district, what we need to do is find purpose for students — in education, in the classroom, in a school — a sense of belonging,” he said.

But that process also starts at home, and he asked parents to talk to their kids and alert district officials if something is off, so they can find ways to help.

For Gomez, feeling safe at school wasn’t something she worried about until she got to high school. Following the attack at Eldorado, students began walking together in groups and were more cautious about their surroundings, she said.

While she understands the new territory the district is navigating when it comes to addressing the recent bouts of violence, she said school should ultimately be a place where students feel safe.

“What happened at Eldorado was a wake-up call,” she said. “Action is only taken when something horrible happens.”

The challenge of retaining teachers

As students step onto school buses and meet their new teachers Monday morning, classrooms will be 92 percent staffed with teachers and school buses 94 percent staffed with drivers, according to director of recruitment Brian Redmond.

Come Monday, classroom vacancies will be covered by substitutes or by school district central office administrators, which may include Redmond himself, who is fourth on the list to be called in.

“We’re going to make sure every classroom is covered no matter what,” he said.

Those staffing levels come as school districts across the country grapple with teacher shortages as educators exit the profession on the heels of the pandemic, citing burnout at higher rates than workers in other industries.

In mid-July, the district had more than twice as many job openings than it did for the same period in previous years, according to data obtained by the Las Vegas Review-Journal.

In an attempt to recruit more teachers, the district earlier this year announced a starting pay bump of more than $7,000 for teachers throughout the district, bringing the starting teacher pay from $43,011 to $50,115. It also authorized retention bonuses of $4,500 and $5,000 for current district employees.

Clark County schools, which make up the fifth-largest district in the country, have not been fully staffed since the start of the 1994 school year, Jara said.

But for Carmen Andrews, a Spanish teacher who teaches online classes through the Nevada Learning Academy, retaining teachers should be as important to the district as recruiting new ones.

Teachers who have been in the district for several years and who made just above the new salary floor are now making just slightly more than a new teacher.

“They don’t realize that when you benefit somebody and hurt someone else in the process, that’s really not a good way to do business,” Andrews said.

In the past, she said, the district may have been able to easily go out and hire 1,500 new teachers at the start of every school year, a practice that she called “recycling teachers.”

“Now that there’s a shortage nationwide, they’re kind of stuck,” she said. “There’s just not the numbers coming into teaching anymore. We’ve kind of created a profession that from the outside looking in doesn’t seem like a great job.”

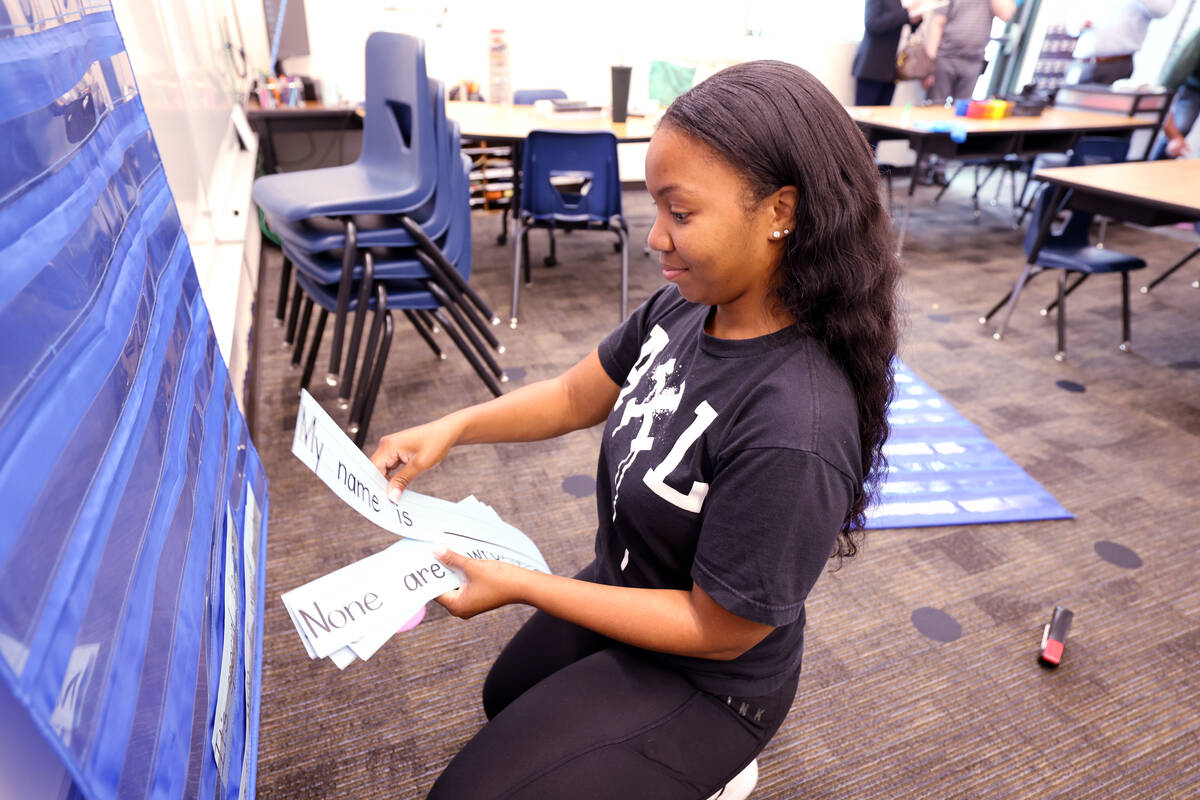

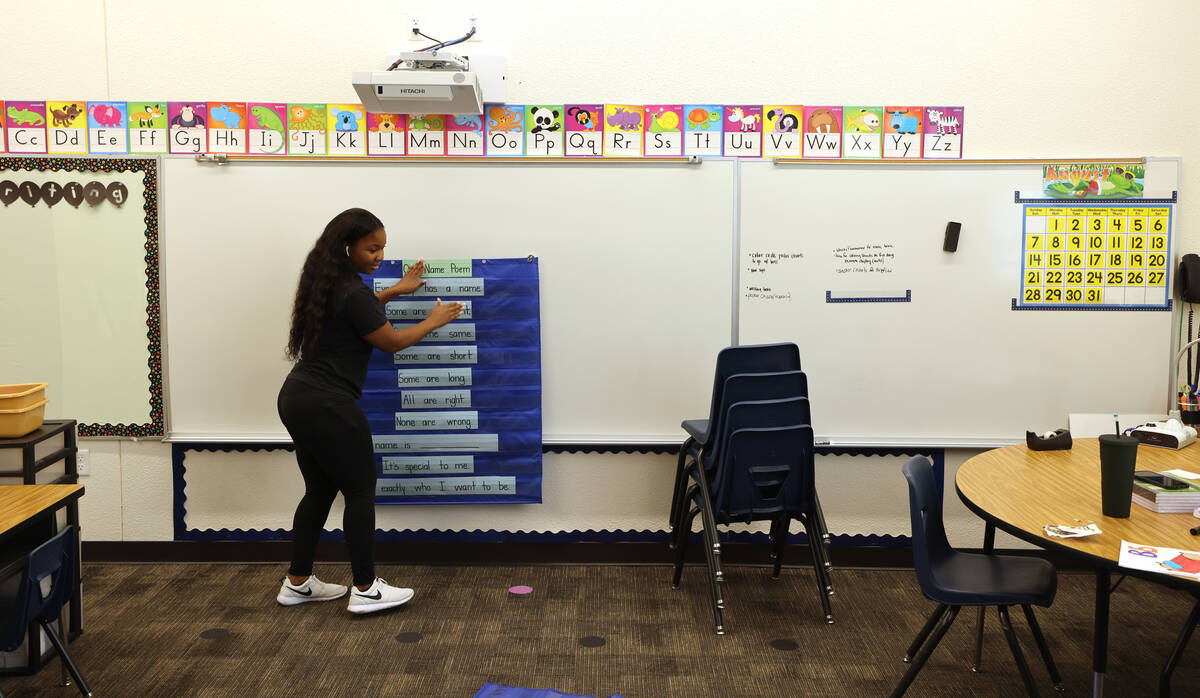

On Thursday, Nyjaa Peterson, a kindergarten teacher at Bell Elementary, readied her classroom for the new school year. Peterson is entering her seventh year of teaching kindergarten at the school, and on Thursday, knelt on the floor of her classroom as she assembled a poem for her incoming kindergartners to use to introduce themselves to their peers on Monday.

Peterson said she’s considered leaving teaching over the last two years, citing the pay, the learning curve and stress of having to teach kindergartners online and capture their attention remotely.

But Peterson said she ultimately loves what she does.

“I think that’s what always kept me coming back is just I actually love being a teacher and the little ones,” she said. “Here I am, another year.”

School board dysfunction

The start of the school year also comes just three months before a general election that will see three school board members’ seats up for grabs.

The seven-member board, which oversees the district of more than 300,000 students, has had a tumultuous year that saw, among other things, the firing and rehiring of Superintendent Jara, concerns over a hostile workplace and board meetings where audience members have been escorted out by police.

Rupp, the district parent, called the meetings a joke and lacking in professionalism.

For Board President Irene Cepeda, too much of the board’s time was spent last year on issues other than student achievement.

Cepeda, who was the swing vote to rehire Jara, took over as board president in January and has repeatedly called for decorum from board members and audience members.

In June, she highlighted several social media posts from her fellow board members that she called unprofessional, negative and out of control.

Heading into the new school year, Cepeda said she wants to prioritize making sure that student-centered outcomes are at the forefront of every meeting.

“It’s where we can do the most good,” she said.

All three incumbent trustees will advance to November’s run-off election.

Cepeda will face off against newcomer and progressive advocate Brenda Zamora, Danielle Ford will face off against former Democratic state Assemblywoman Irene Bustamante Adams, while Trustee Linda Cavazos will face off against retired former teacher and administrator Greg Wieman.

Declining enrollment

The district had 319,917 students during the 2019-20 school year and is projecting 299,038 for the upcoming school year, a 6.5 percent drop in enrollment, according to a recent presentation to the State Board of Education.

Across the country, nearly 1.2 million students left public schools during the 2020-21 school year, and enrollment recovered faster in districts that returned to in-person learning more quickly, according to a national enrollment analysis from the American Enterprise Institute, Washington, D.C.-based think tank.

Private school enrollment in Clark County also increased by 10 percent from the 2019-20 school year to 2021-22, according to numbers from the Nevada Department of Education.

When the district halted in-person learning and pivoted to distance education, families that had the ability to put their kids in private schools that remained open did so, according to Jara.

But Jara said it was misguided to say that public schools aren’t working. Public schools can compete, and the district has seen students coming back from charter schools and private schools.

“If parents want to exercise their choice, that’s fine,” he said. “I want to be their choice.”

Rupp, the mother who homeschooled her son, sends her daughter to public school because of the individualized education plan and vision services that are available to her there. Rupp and her daughter are both blind, and the mother said she was told early on that her daughter wouldn’t be able to get the same services if she were to go to a private or charter school.

“It just makes more sense for us to go to our neighborhood public school,” she said. “Especially for me as a blind mom, if I need to get to my kid’s school for an emergency, it’s easier for me to get transportation to get there.”

But ahead of Monday, many in the school community are reflecting on how the pandemic has become a pervasive presence and affected “normal” school operations.

Andrews, the Spanish teacher, said schools and teachers have been battling issues of burnout and low pay for a long time, but the pandemic has created a “whole new normal.”

“I think teachers are just tired,” she said. “I think a lot of people feel we’re just limping in (to the school year).”

For Gomez, the Las Vegas High School junior, the pandemic also hit hard. She forgot how to make friends and how to socialize. It’s something she considers when she reflects on what’s driving the wave of violence she’s been reading about in news headlines for the last year.

“You’re so isolated for so long you forget how to talk to people,” Gomez said. “I think a lot of it has to do with the world we live in now. The world has changed a lot. I guess it’s gone haywire in a sense.”

Contact Lorraine Longhi at 702-387-5298 or llonghi@reviewjournal.com. Follow her @lolonghi on Twitter.