COVID-19 threatens Nevada child care facilities as demand rises

Before the COVID-19 outbreak, Rising Star Preschool & Childcare was debt-free, its two centers were full and it had a waiting list of 18 children. Today it has 25 vacancies at its Las Vegas center and 20 more at its facility in Henderson.

The need for licensed child care centers, already in short supply before the pandemic, is expected to increase dramatically as more parents return to work in the coming weeks and months. But as demand rises, day care providers that serve infants through age 5 are struggling to overcome the financial impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Already, 14 preschool and child care programs in Nevada have closed since March, though it’s not clear how many of those were caused by the pandemic, while many others remain at risk of shutting down.

Parents with older school-age children in Clark County are facing a similar conundrum when the next school year begins in August. The Clark County School District is expected to adopt a “blended” learning plan that would see two cohorts of students attending school in person for two days a week and learning from home for the other three.

The issue of how parents will be able to arrange care for their kids during weekdays when many are working was a major point of concern among parents who submitted questions at Thursday’s CCSD board meeting to evaluate the plan.

Nevada child care centers and preschools were deemed essential businesses and allowed to stay open throughout the spring. But the financial shock to many of the businesses, including parents withdrawing their kids out of health concerns or after being laid off, put many quickly into the red.

Tina Fox, who owns Rising Star Preschool & Childcare, said she has managed to keep her business running, though at a financial loss, after the pandemic initially cut enrollment by 55 percent at its Las Vegas center and 40 percent at its Henderson center.

As a result, Fox said, she now has plenty of openings.

She also had to furlough six of the centers’ 27 employees and take out a U.S. Small Business Administration loan with a 3.75 percent interest rate to help weather the storm. And unlike some other government aid for small businesses, she’ll have to pay that back.

“It’s still debt, and we didn’t do anything to create that,” she said.

Fox sees a long road back for her business and other child care providers.

“For any of us in the industry, I think it will take us a good year to even start to recover from it,” she said.

Permanent closures

Since March 1, 14 licensed child care providers — either in-home or center-based — across Nevada have permanently closed. Of those, 11 are in Southern Nevada. Reasons for the closures include financial hardship, retirements, relocations and landlord issues.

The Nevada Department of Health and Human Services, which oversees child care licensing, released the data in response to a Review-Journal inquiry. The information did not include specifics about what age range of children were served and which providers offered preschool in addition to child care.

Two providers that permanently closed this month — The Learning House of Las Vegas and Little Timbers Academy-Hot Springs in Carson City — listed this reason: “financial hardship due to COVID-19; applied for CARES grant but it was not enough to sustain the facility,” according to state records.

The Learning House of Las Vegas opened in June 2017 and offered a half-day Montessori-based preschool program. It closed June 15. State records show it had a 14-child capacity.

Owner Jen Harrington said in an email to the Review-Journal that The Learning House of Las Vegas was a “small, one classroom program” with two full-time employees, including herself, and one part-time employee before closing March 16.

Since class wasn’t in session and a reopening date was unknown, Harrington and her business partner — her husband — decided to refund tuition to families for the rest of the spring semester.

“From the first day we closed, parents frequently reached out to tell me how much their children were asking about going back to school,” Harrington said.

She created videos most weekdays from home — which included reading a story and sometimes singing a song — to try to give children some semblance of classroom group time, she said.

Earlier this month, Harrington shared new health protocols from the state and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention with clients and interested parents and asked when they expected to feel comfortable sending their children back to the center.

“Based on the survey results, the business side was simply not financially viable moving forward,” Harrington said of the decision to close permanently.

The center had two years left on its lease, but the landlord “was generous in helping us with an early termination,” she said.

Another Las Vegas preschool program — Far West Academy — lists “lack of business” as the reason for its closure, effective April 30. State records show a 56-child capacity. The school’s Facebook page says it’s a private, religious-based preschool through 12th grade school.

Others on the list include KinderCare Lake Sahara in Las Vegas — with a 134-child capacity — which closed April 29 because of landlord issues. And Oaklane Preschool Academy in Boulder City — with a 40-child capacity — closed March 31 because of a retirement.

Officials from Far West Academy, KinderCare and Oaklane Preschool Academy weren’t available to comment.

Oaklane Preschool Academy closed after 44 years in business, according to an April story in the Boulder City Review. Owner Carole Gordon said the COVID-19 outbreak and a new preschool being built next door contributed to her decision to close, according to the story.

A nationwide issue

Before the COVID-19 shutdown, it was already a challenge for parents to find affordable child care. In April, the Center for American Progress estimated the number of available child care slots at risk of disappearing without additional federal support. Nevada, which had a worse shortage of available child care slots than the nation as a whole before the pandemic, could lose up to 42 percent of its overall supply — or the equivalent of 17,302 slots — according to the group’s projections.

In March, the National Association for the Education of Young Children surveyed more than 6,000 child care providers. Of those, 30 percent said they wouldn’t survive a closure that lasted more than two weeks without significant public investment and support.

In April, Save the Children Action Network and Child Care Aware of America announced results of a national survey of 1,200 registered voters. Of those surveyed, 87 percent “support providing enough federal assistance during the crisis to ensure current child care providers are able to make payroll and pay other expenses, such as rent and utilities,” it said in a news release.

The nation’s child care industry was facing a crisis before the COVID-19 outbreak, said Roy Chrobocinski, director of federal government relations for Save the Children Action Network. But he said having safe, affordable care for children is key to reopening the economy.

Depending on the state, centers may be limited in how many children they can accept because of social distancing requirements, he said, at the same time they’re facing extra expenses for cleaning and other services.

Also, child care workers tend to be low paid, Chrobocinski said, adding that those who’ve experienced a job loss are probably doing better receiving unemployment benefits than what they made on the job.

Pain for parents

When the COVID-19 outbreak hit Nevada, Las Vegas mother of three Meredith Noce kept her two youngest children, ages 2 and 3, out of their child care center for eight weeks. Then her husband was laid off from his job.

Noce said she was able to get a freeze on her account at the child care center. But she said she has talked with other parents who had to pay to hold their child’s slot even when they weren’t attending classes. And some who’ve returned were required to pay registration fees again.

Noce said her kids went back to their child care center two weeks ago.

“Working from home with them, it had its challenges,” she said. “Every meme out there is 100 percent accurate.”

When she called the center, she was told she could bring her children in that same day, if needed.

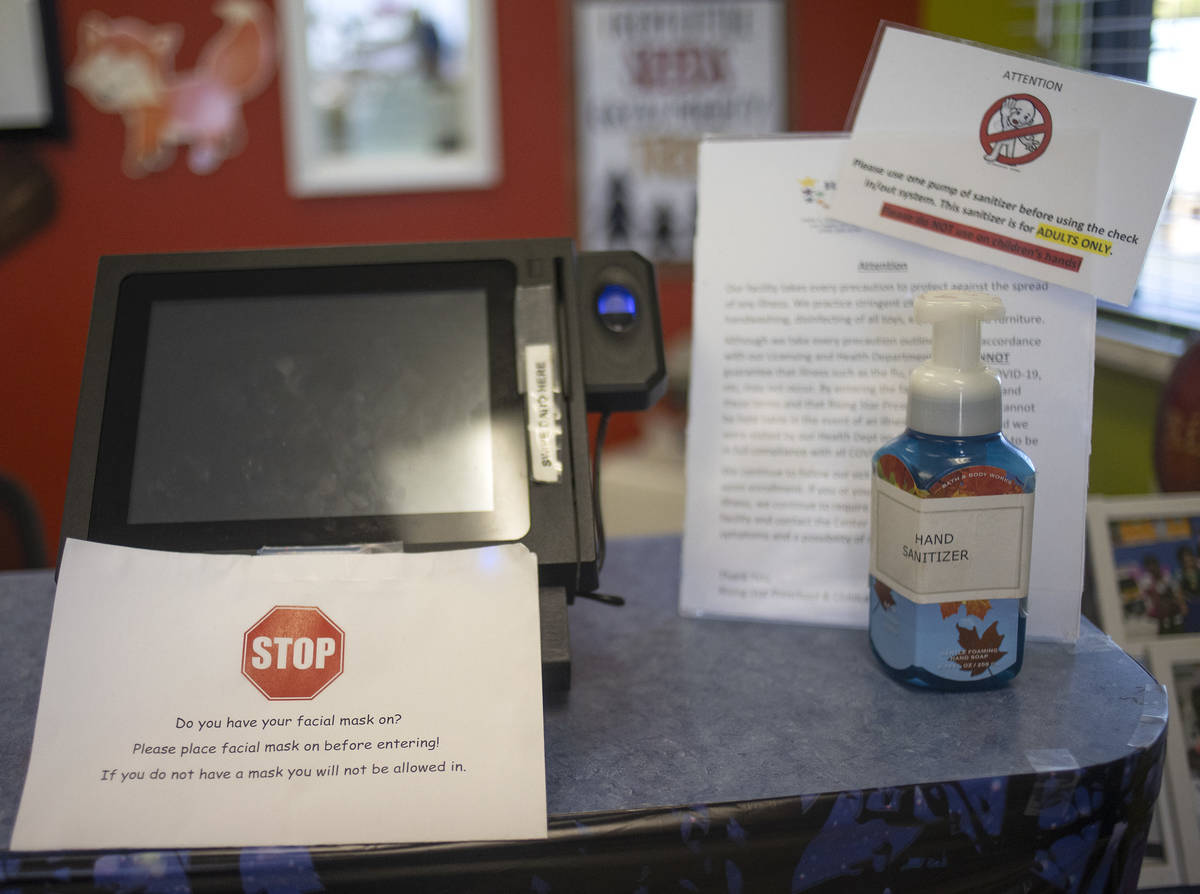

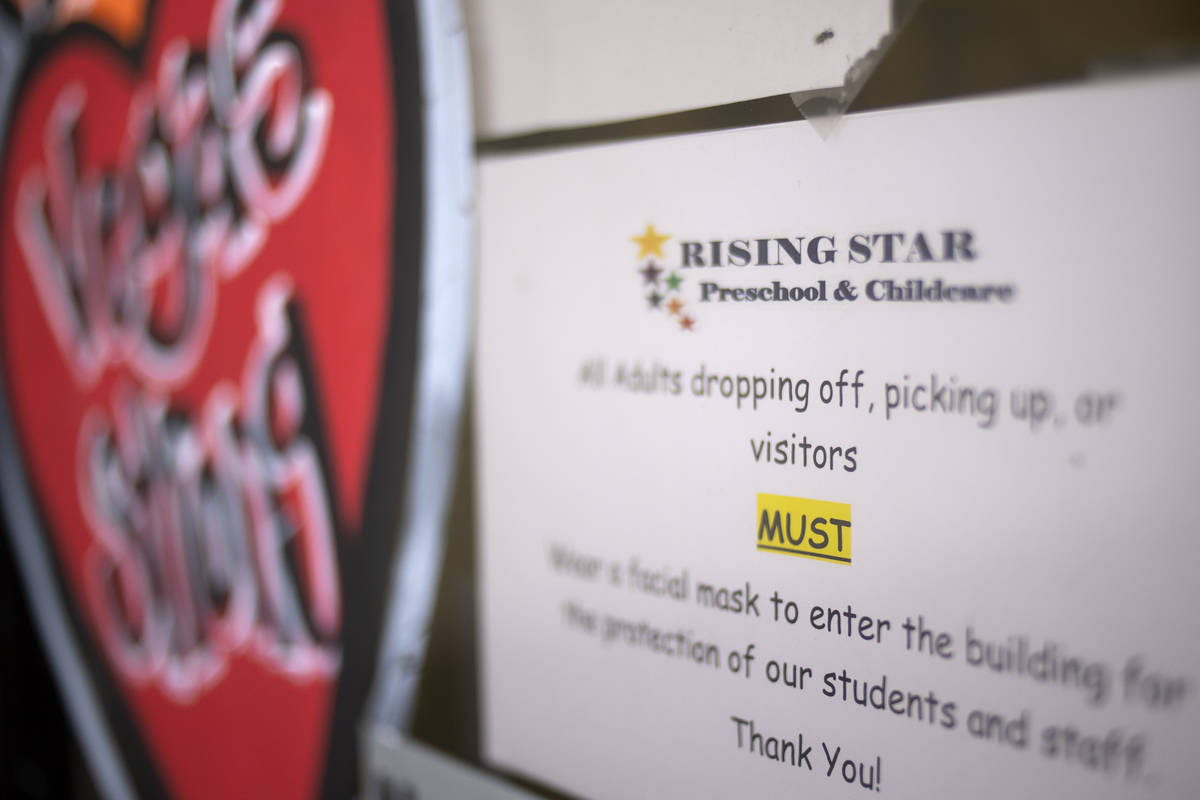

“They have just been wonderful,” she said, noting the center has also taken many health and safety precautions.

One Clark County School District teacher, who spoke with the Review-Journal on condition of anonymity out of concern about reprisal in the workplace, said Thursday she’s worried about child care for the upcoming school year.

The teacher, who works with high school English language learners and is a single parent of two kids, a son entering kindergarten and a daughter in sixth grade, said she has no idea how she will manage in the fall.

The teacher said her son’s day care, a licensed in-home provider, closed in the spring and hasn’t reopened.

Her original plan was to have him attend the Safekey program in North Las Vegas. But she hasn’t heard whether the program will operate as usual in the fall.

She said she could probably leave her sixth grader home alone during online learning days. But she said unless she finds another child care option, she’d have to bring her kindergartner to work with her even though that probably wouldn’t be allowed.

“At this point, I don’t see any other way to do it,” she said.

Families with school-age children often rely on programs run by nonprofits and Safekey, a before- and after-school program run by local governments. Some schools also offer their own programs.

Clark County, Las Vegas and North Las Vegas officials said they didn’t have information Friday about what they’ll be able to provide for the next school year.

But Andy Bischel, president and CEO of the Boys & Girls Clubs of Southern Nevada, wrote in a Thursday email to the Review-Journal that the nonprofit will be able to serve fewer than the daily average of 1,500 children it oversaw at 13 club sites until the pandemic because of reduced capacity due to social distancing requirements.

Some centers have openings

At Rising Star Preschool & Childcare, “a lot of people think we stay open because we just want money,” Fox said, but noted families rely on the center.

Of the parents who pulled their child from the center, most were laid off from a job, Fox said. “Even now with things reopening, you’ve still got people at home who are not working.”

Fox said she has offered many options for families, including paying to hold their child’s spot until they’re ready to return or reducing fees for those that pulled their child out on a short-term basis such as for two weeks.

For families who’ve withdrawn their child, they’ll come back like a new client and registration will be done again, she said.

At Rising Star’s Las Vegas center, there are six classrooms and only two were open shortly after the COVID-19 outbreak struck. Within the past couple of weeks, two more reopened.

Summer is usually a little slower time of year under regular circumstances, Fox said, but she’s hoping to see a “decent increase” in enrollment by fall.

At Faith Lutheran Preschool in Las Vegas, employees were paid during the center’s six-week closure from March 17 to May 1 and continued to share curriculum and stay connected with families, director Tonia Tate said in email to the Review-Journal.

The center was operating at low capacity in May, with 44 students, she said. That grew to 61 students in June and July for its summer camp.

“Our hope is we can open at full capacity in August with approximately 250 students,” Tate said. “All our summer staff are currently working. Most of our lead teachers have elected to be 10-month teachers so they do not work in the summer months.”

Shenker Academy in Las Vegas closed for three weeks starting in mid-March but reopened in early April — initially, just for children of essential workers, Head of School Sharon Knafo said. There were typically nine to 12 children a day.

The academy usually has about 80 employees, but laid off 70 initially when the COVID-19 outbreak hit. Now, about 25 are working.

In early May, the academy reopened to all children.

Before the COVID-19 outbreak, Shenker Academy, which cares for children from 6 weeks old through kindergarten age — typically had 230 students on any given day. Now, the academy has about 50 percent of its normal enrollment, compared with last summer.

Saint Gabriel Catholic Preschool in Las Vegas — which had up to 17 children before the COVID-19 outbreak — started seeing an enrollment drop in March. At one point, only one or two were showing up.

The center temporarily closed March 18 and reopened June 1. But the church also runs an elementary school, which won’t be open next school year because a benefactor pulled out, preschool director Pamela Ufer said. The school’s website says it serves up through middle schoolers.

As for the full-time preschool program, all of the employees were furloughed when the center closed, but Ufer said they were paid through March 30. Now, employees are back at work.

On the first day of its reopening, four children showed up. As of the week of June 8, seven to eight children were attending.

“It’s slowly coming back, as you can see, as the parents go back to work,” Ufer said.

Before the COVID-19 outbreak, the preschool center — which is about 3 years old — was starting to pick up momentum, Ufer said. “Now, it’s starting over again.”

Contact Julie Wootton-Greener at jgreener@reviewjournal.com or 702-387-2921. Follow @julieswootton on Twitter. Reporter Aleksandra Appleton contributed to this report.