Elementary school overcomes language barriers

Sink or swim. That's been the reality lately for Bendorf Elementary School.

The once-affluent, primarily Caucasian neighborhood has shifted from homeowners to foreclosures to renters. More children are poor, a known hindrance because hungry children are unfocused students.

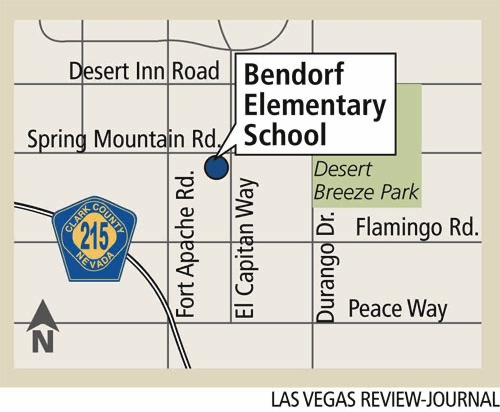

More aren't only unfamiliar with English. They've never spoken it. And their first languages aren't just Spanish, but Korean, Russian, Arabic and about 10 others. The school, on Spring Mountain Road east of Fort Apache Road, has even seen an influx of French-speaking Ethiopians.

Some have never been in school before, said counselor Deborah Rowe, who is the first person new students see.

"It's a challenge to get them to sit still in a chair," she said. "Some have never seen scissors."

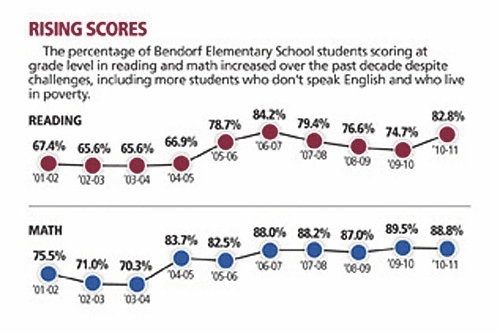

Despite all that has been stacked against Bendorf and its 850 students in the past couple of years, the school has left the Clark County School District in the dust. About 83 percent of Bendorf students are reading at grade level, towering over the district's average 60 percent, according to Nevada's standardized tests for third through fifth graders. Nearly nine of 10 Bendorf students are at grade level in math compared with 68 percent of Clark County students.

And the school has caught the attention of the U.S. Department of Education, which placed Bendorf in the top 1 percent of America's improving schools on Thursday, earning it a Blue Ribbon award. No other Nevada school did the same, but Advanced Technologies Academy earned a Blue Ribbon in the only other category, high achievement.

Oddly enough, Bendorf's students actually were doing worse a decade ago when the mostly Caucasian and middle- to upper-class students were statistically favored to outperform. About 14 percent fewer students were at grade level then.

How is that possible?

The simple answer: When Bendorf's teachers recently revolutionized their methods to reach all corners of the diverse classroom, even those who couldn't speak a word of English, every student benefited. That's the claim of Principal Joanna Gerali-Schwartz, who has been at the school two years and advocates active teaching.

The difference is clear within minutes of watching Kathryn Ulin at the front of her fourth-grade class, not talking at students but with students. Just about everything she does isn't only instructional but visual, and interactive with the class.

Friday morning's topic was rounding numbers. All fourth-grade teachers are tackling the same hard-to-grasp topic. Teachers meet every week to coordinate curriculum, considering not only their grade but all grades, kindergarten through fifth, the principal said.

"What do we do because of this number to the right?" Ulin asks after writing a seven-digit number on the whiteboard.

Students raise their hands high. And it's not just a couple of overachievers. Just about everyone stretches an arm straight up, as if trying to graze their fingers against the ceiling.

"Five or above, give it a shove," says the boy she calls on.

"What if it were less?" she asks.

The whole class shouts in unison, "Four or less, don't mess."

Math is also the best way to reach non-English speakers and keep them engaged, the principal said. Numbers are universal.

Ulin could give each student a worksheet to sit quietly and scribble in the answers. But she doesn't do that in class.

"Is it a little noisy this way? Yes," says the principal sitting in the back of the room. "Does she have control? Yes."

To make sure everyone's participating, Ulin will occasionally draw names from a cup to answer questions.

Technology also helps. SMART Boards combine the whiteboard with the computer, also allowing each student to simultaneously answer questions with handheld clickers. Ulin then can instantly see which students answered correctly, and which students didn't.

But it comes down to the teachers, counselor Rowe said. Many of the parents now work nights, so no one is there to help students with homework, unless they have older siblings.

"We have staff who won't take a lunch but eat in their room to help kids who need extra help," she said. "Or they come in early."

The principal and school keep data for everything and every student, like stats for an athlete.

"We're very data driven," Principal Gerali-Schwartz said. That way, nothing is done in a gut reaction, but backed by fact and research showing that it works.

Work, it has. Even the usually underperforming groups are excelling. Hispanics, usually the largest group of English learners, increased their percentage of students writing at grade level by 35 percent last year.

That surpassed staff's expectations, said Ulin, who put together Bendorf's application for the Blue Ribbon award.

No monetary reward comes from winning the Blue Ribbon. No tangible benefit.

"If anything, it will cause more zone variances that I have to deny because we're overcrowded," Gerali-Schwartz said. "But it will give teachers the recognition they deserve."

Contact reporter Trevon Milliard at

tmilliard@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0279.