How distance learning is affecting parents and teachers

Three kids. Two jobs. One worked-to-the-bone mother.

You hear it in Krystal Shen’s voice: composed, yet occasionally fizzing with frustration, like an effervescent splashed into water.

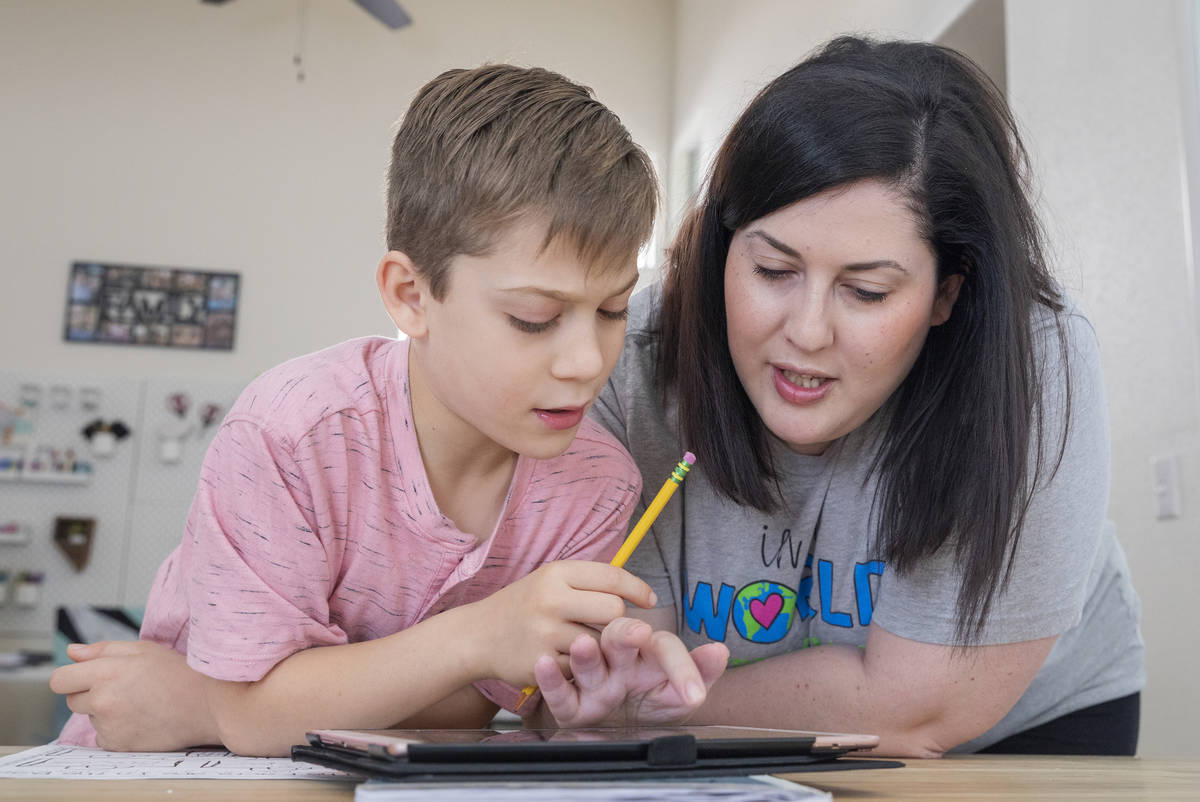

A health care worker, Shen’s a mom to a pair of high schoolers and a fourth grader.

On March 15, when the Clark Country School District announced that it was closing its classrooms because of coronavirus concerns, Shen abruptly, jarringly, uncomfortably obtained yet another job title: teacher.

Her older kids can handle online learning on their own, for the most part.

But her youngest requires hands-on attention.

“Trying to find the time to do schooling with him is very difficult,” Shen says. “He can’t navigate it on his own, so I have to sign on and help with each assignment and make sure he gets to the right website. Last week was busy, so we ended up a week behind on assignments, and I got an email saying he was failing two subjects because of it. We’re trying to catch up this week, but I just don’t understand how they can expect parents to all of a sudden become the teacher regardless of your home situation.”

[In their own words: Clark County students on distance learning]

And so it has gone for many parents around the valley as they’ve been thrust into the role of being educators to their kids. The impact has been profound, with ramifications that extend far beyond the current school year — even if those ramifications aren’t totally clear. One thing is certain in these uncertain times, however: The emotional toll has been palpable for all parties involved.

“You can’t throw someone in a job that someone had to go through four years or six years of college to do,” says Donna Wilburn, a Las Vegas marriage and family therapist at Red Rock Counseling. “Nobody was taking into consideration the psychological stress that this situation has had on kids and parents. Even though the kids aren’t going to the school, they still feel the pressure of doing the work, and the parents have an extra job during a time when they’re already stressed out. This, to me, is a nightmare for so many families.”

The strain hasn’t been felt by mom and dad alone.

“We were plugging along, test scores were going up, and then bam, it’s like the virus hit us with a baseball bat,” says Tam Larnerd, Spring Valley High School principal.

Immediately grades went out the window.

“Anything they do, we can’t really assess it because we’re not there to actually teach them how to do it,” says CoCo Thomas, a music teacher at Mack Middle School, explaining the lack of grading during distance learning. “So if they’re doing it wrong, we can’t give them a bad grade.”

It’s been a lot for teachers to process.

“It just starts to wear on you when you can’t see the end,” says Amy Brown, a music teacher at Dearing Elementary School. “I did cry some days, as it just gets to be too much. Then, adding the well-being of my students in there, it adds another layer of hurt. Are they getting enough food? Are they safe? Teachers are sometimes the only ‘norm’ that is left in some of their lives.”

Learning on the fly

It was as sudden as it was seismic, an educational U-turn with a learning curve shaped like a pretzel.

When distance learning protocols were adopted in March, there was little warning.

“We left on a Friday, writing new objectives on the board, getting new materials ready for the following week, only to never set foot in the classroom again with our students,” Brown says. “Suddenly, we were expected to teach from home with no training on how to deliver materials from afar or even how to find digital materials. We also had none of our regular equipment or materials to effectively teach our students.”

Some things, however, have remained constant.

Teachers still log full work days and are required to keep in contact with their students, though the extent to which they need to do so varies. Some schools require teachers to check in with all their kids once a week, and some limited the contact to pupils in one period they teach.

Grades mostly were frozen at what they were when the third quarter ended. Teachers continue making homework assignments in some cases, though nothing is graded. The district left it open to teachers and principals to decide whether they should even present new material.

Students can, however, earn extra credit by completing their work or redoing previous assignments, thus enabling them to raise their third quarter grades. (Some charter schools have continued to grade assignments, though, such as Coral Academy of Science, which Shen’s fourth grader attends).

“Third quarter is unlocked, so kids can go back and redo any assignments they want,” says Jessica Houchins, a counselor at Mack Middle School. “For middle schoolers and high schoolers, that’s a really crucial thing. A lot of people think, ‘Well, grades don’t count right now,’ but I’m counseling my students, the ones who have D’s or F’s for quarter three. I’m like, ‘Get back in there. Ask that teacher if you can retake that quiz, ask that teacher if you can redo that math.’ ”

This scenario is not unique to Las Vegas.

Tulane professor and Brookings Institute author Douglas Harris says most districts have decided to emphasize pre-closure grades out of concern for students who can’t access distance education.

“There’s a feasibility question here,” Harris says. “Whether students have a computer and internet access, whether teachers themselves have those things, or have their own young children at home and have personal responsibilities to attend to. All of those factor into what should be expected.”

So teachers have been plunged into uncharted waters to navigate in ways that they see best for themselves and their students.

At Roberts Elementary School, for instance, some kindergarten teachers dropped off homework packets to their students each week; others relied solely on online platforms to educate their kids.

It’s been an adjustment either way, especially when using internet applications such as Google Classroom.

“Teaching through a screen is so impersonal,” says Juan Plascencia, a social studies teacher at Canyon Springs High School, who is moving to Las Vegas Academy in the upcoming school year.

A professional musician, too, Plascencia likens the experience to attending a concert.

“You can watch livestreams from Metallica,” he says, “but you know the difference between actually going to a show and watching it in on a screen. It’s the same thing with teaching.”

For educators, connection is key, which can be a challenge to develop and maintain from a distance.

“The school counselor relationship is built on human connection, face to face,” says Houchins. “It’s been really difficult for me to adapt, because the kids who come and visit me every day are the ones who are storming out of the classroom, the ones who are upset about something at home, and now those kids aren’t reaching out to me anymore because of connectivity issues or maybe there’s abuse happening at home or maybe apathy or maybe mental health issues.

Then there’s the question of access.

“I wish I could do home visits, and just sit 6 feet away at the door, just so they know I’m there,” Houchins says. “Am I adapting? Sure, I set up appointments, but they have to click the buttons and set up the technology, and maybe they don’t have parents at home that are helping them figure out how to do that and talk to me. Maybe they don’t want me to see what’s inside their home, maybe they’re in too small of a space, they don’t want their parents hearing them talk to me. So, I do miss my office. I do miss that connection. I miss that confidentiality. It’s been really hard.”

Still, teachers are working to make the best of difficult circumstances.

Thomas has taken advantage of distance learning by broadening her curriculum in new ways.

“I use this time to teach things to my students that I might not necessarily have time to in the classroom,” she says. “Some kids have stepped up during this time. Some kids that maybe they weren’t so great in the classroom, this is their time to be like, ‘Oh, these are the things that I can do.’”

Other teachers have embraced fresh methods of reaching their students discovered during distance learning.

“One thing that I’ve actually enjoyed about this time is that I’ve learned so much about how to integrate new technology into the classroom,” says Christopher Houchins, a kindergarten teacher at Ortwein Elementary School and the husband of Jessica Houchins. “There are a lot of resources out there online for teachers that I wasn’t as aware of before the pandemic happened. There is so much out there that I’m finding every single week to use that just makes me a better teacher.”

Still, finding a silver lining to a cloud-covered fourth quarter doesn’t dispel those clouds. A sense of loss still lingers.

“For me, the thing that I have to avoid thinking about, so that I don’t get sad, is the amount of learning that happens all year,” Thomas says. “This year, I just felt like a lot of learning happened, and then once quarantine hit it’s like, ‘Is that all gone?’ We were just reaching that peak, the energy was feeling good, and then all of a sudden, it’s gone.”

Parents as teachers

The guilt.

It’s as heavy as a Buick with an anvil in the trunk.

The idea that, as a parent, you’re not doing enough to educate your child is a feeling akin to traversing emotional quicksand.

“I had a lot of parents reach out to me and express that same sentiment,” Christopher Houchins acknowledges. “They said that they weren’t doing enough, that they were effectively letting their children down.”

Laura Lindstrom has been there.

“I feel the guilt, and some days it really gets to me,” says Lindstrom, a mother of 7-year-old triplets and a 5-year-old with special needs. “I’m crying because I’m not doing what someone else is.”

For some parents, just getting their heads around what their child is supposed to be learning can be a struggle, especially with today’s teaching methods, which may have changed since they were in school.

Clarissa Acosta, an interventionist at Beatty Elementary School, recalls a friend of a friend contacting her out of frustration with the way math is taught currently.

“‘You need to help me,’ Acosta recalls her friend saying. “‘I don’t understand how they’re doing this. I’m trying to teach her math my way, and they don’t even do it that way anymore. They use different terminology. It’s all different.’ And this is just fourth grade math.”

Today’s technology also presents challenges for some families.

“If you’re a parent who’s not tech savvy and you don’t know how to submit a screen shot to your child’s Google Classroom, that takes some help and skills, too,” Brown says. “If you have working parents, it’s kind of a juggling act if you only have one or two devices, you have four kids, and you’re supposed to be on a Zoom meeting with your boss and you have a Google meet at the same time. As a parent, it’s like, ‘How do I decide which is more important? Is my job more important or is my kid’s education more important?’ ”

Lindstrom has experienced this firsthand.

“If my husband is on a business Zoom,” she says, “and the teachers are asking me to Zoom, which means that I have to supervise my children directly, I have three other ones running around screaming, so my husband cannot do his job professionally.”

And there are those households that lack the necessary technology altogether.

“There are families who don’t have Wi-Fi,” Plascencia says. “There are families who don’t even have a smartphone. There are students at the secondary level whose contact information doesn’t work because their phone has been disconnected or their email is not real, and out of shame, they have to put something down. It’s a huge issue.”

Still, some parents have found benefits in distance learning.

Danille O’Hara, owner and founder of concerts and events company Nevermore Productions, says the transition has been smooth for her 9-year-old son, a third grader at the Doral Academy Red Rock charter school.

“We’ve actually had a really positive experience with this, with everything else going crazy,” O’Hara says. “He focuses really well when it’s just him and no other distractions. That does help. But he misses being around the other kids. He misses the interaction.”

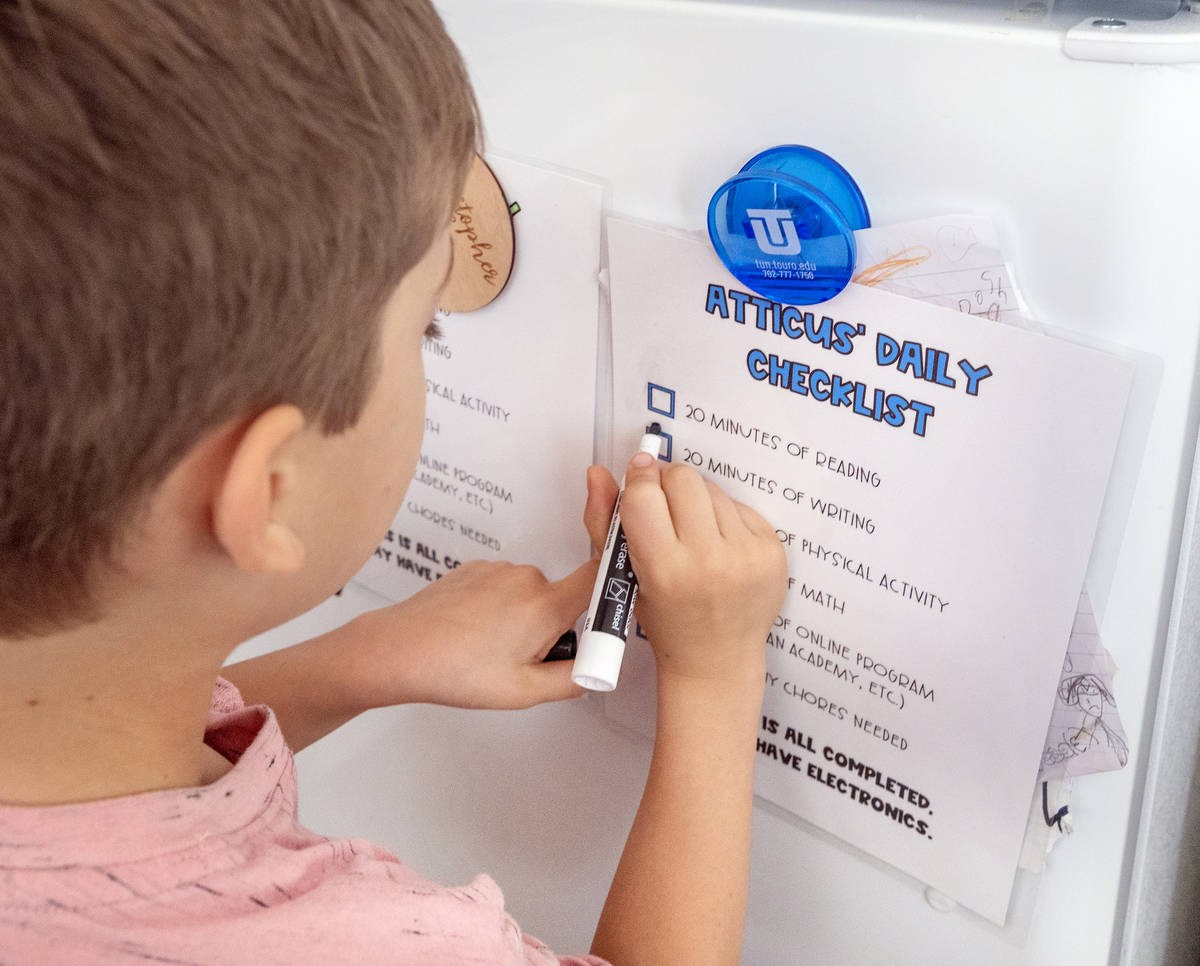

With kids no longer in classrooms, parents need not try to duplicate the classroom experience at home.

“I had a lot of parents who kind of approached this as, ‘My child has to be reading, has to be writing, from 8 o’ clock all way to 6 o’ clock, just like normal,’ ” Christopher Houchins says. “I actually had to give some resources and some research to my parents and say, ‘Actually that’s not the right way to go about it.’

“Whatever you’re doing is enough,” he continues. “Even if you’re just reading with your child 30 minutes a day and having online programs for them to use, you’re doing enough.”

New school year, new approach

What happens when distance learning becomes a distant memory and classrooms open for the new school year in August — assuming they do?

It won’t be business as usual for educators, who already are preparing for how they will compensate for not being able to teach new material during the coronavirus shutdown

“The elementary school teachers have been talking about how they’re just going to have to start with whatever was not taught in the grade before them,” Acosta says. “My school is (holding) vertical alignment-type of meetings, where the third, fourth and fifth grade teachers meet to see what they’ve taught, what they need to teach and what they’re going to be able to pass on to the next grade-level teachers.”

The key will be gauging where students stand with the curriculum that was not taught and graded at the end of this school year.

“One of the things we’re looking at is our MAP Growth Assessment, which really gives us an opportunity to measure where the kids are today. It’s very individualized,” says Clark Country School District Superintendent Jesus Jara of the computer adaptive test that students take two to three times a school year, on average. “ Then the teachers will be able to know what the skills are that the students are missing, the standards that they’re missing, so that we can start finding ways that they can embed some of the standards that are missing from the last marking period throughout the first quarter of next year.”

If what is taught might be a little different at first, so may be the manner in which it will be delivered.

“This experience has forced teachers to break out of their comfort zone to incorporate technology into their teaching,” Brown says. “I would like to see this continue, to some extent, when we return. Hopefully, teachers have found good resources to supplement their content, so when they teach that unit again, why not use a video, website, etc., to introduce or review?”

Ideally, then, the learning experience will benefit from this experience.

“We become better teachers, better people, better moms, better wives, better husbands when you have to adapt a little bit, because you get out of your comfort zone,” Brown says.

“In that realm of things, this has been kind of a positive thing for a lot of us. We grow when we have to change.”

^ Contact Jason Bracelin at jbracelin@reviewjournal.com. Follow @JasonBracelin on Twitter.

Review-Journal staff writer Aleksandra Appleton contributed to this story.