‘Remove the barriers’: Dropout prevention nonprofit expands to more schools

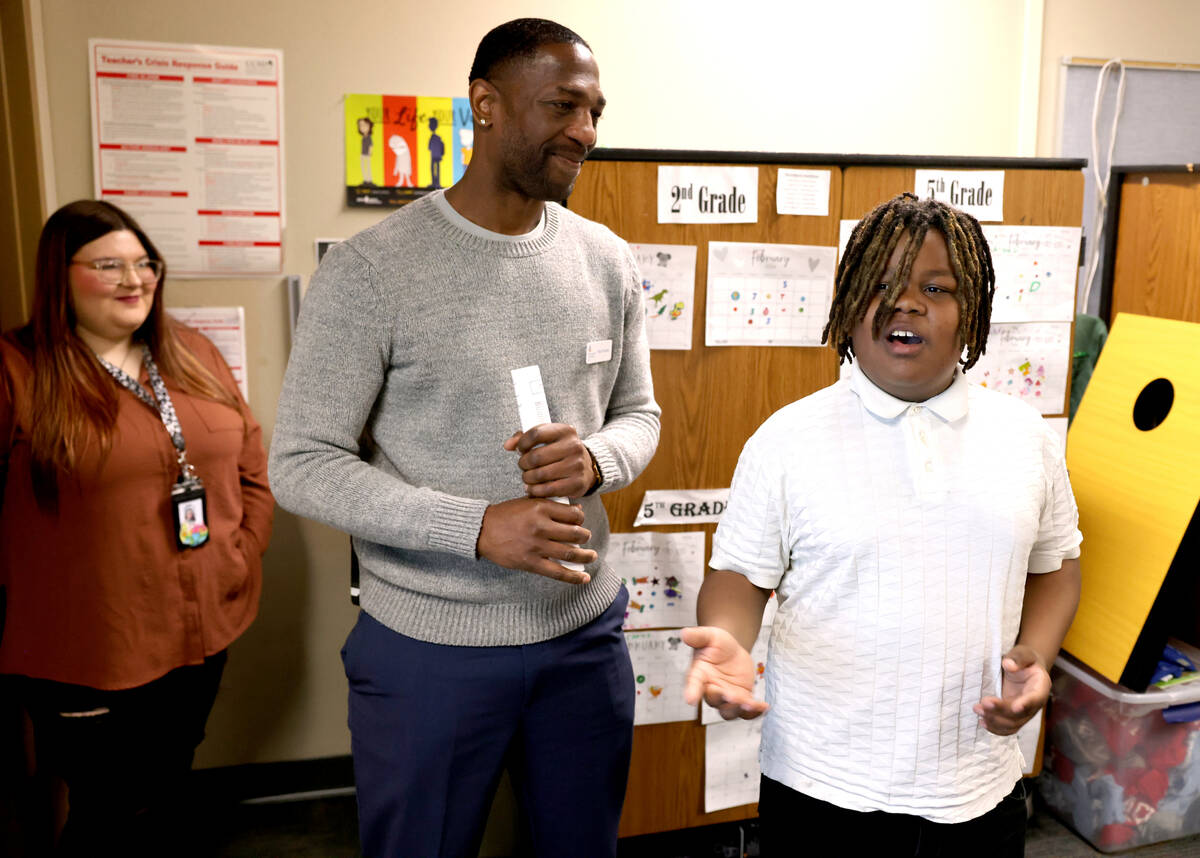

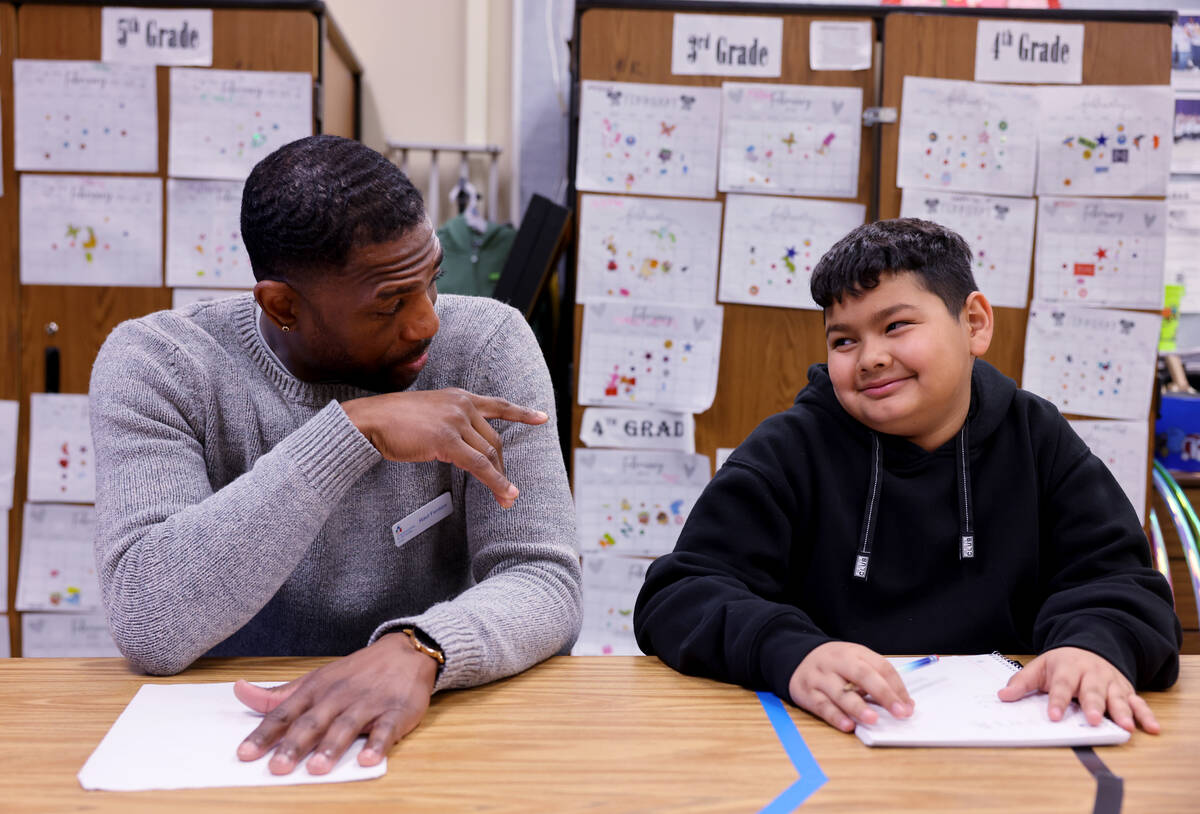

Fifth-grader Freddie Coleman is getting help with learning how to manage anger without even leaving his elementary school.

The 10-year-old is among dozens of students at Lowman Elementary School near the Nellis Air Force Base that are case managed by the nonprofit Communities In Schools, a dropout prevention organization that operates nationwide.

Freddie told a small group of visitors Tuesday inside Communities In Schools’ resource room at Lowman that site coordinators “help me a lot, a lot.”

“It’s like a chill place,” he said about the room. “I love it here.”

Lowman Elementary is among 80 Clark County School District campuses that are served by Communities In Schools of Nevada.

The organization operates inside school buildings, helping to connect students and families with the resources and support they need to overcome obstacles in order to be successful at school.

“We’re here to remove the barriers,” Debbie Palacios, executive director of Communities In Schools of Southern Nevada, told visitors at Lowman. “That’s our mission.”

The state organization has rapidly expanded into more high-needs schools across the state. And there’s a waiting list of 30 schools that want the organization on campus.

“We have grown exponentially over the last two years,” said Tami Hance-Lehr, CEO and state director of Communities In Schools of Nevada.

The nonprofit now serves nearly 40 more schools compared with the number served four years ago. That’s due, in part, to the demand for services to address the lingering after-effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Since the pandemic, Communities In Schools of Nevada has found that “the barriers have just gotten harder” for students and families, Hance-Lehr said.

A 20-year history

Communities In Schools of Nevada began at one school, Martinez Elementary School in North Las Vegas, in 2004.

By the 2019-20 school year, the organization served 72 schools. Now, it operates at 110 campuses this school year.

Nevada is the fifth-largest state office in the national network, which includes 28 U.S. states and Washington, D.C.

The state organization has three regional affiliates. More than 91,000 students attend schools with Communities In Schools of Nevada on campus. And more than 5,900 of those students are case-managed by the organization.

Of the 80 Clark County schools served, the majority — 55 — are elementary schools. The organization also serves 12 middle schools and 13 high schools.

The nonoprofit’s new growth is focused on “feeder patterns,” with the goal of ensuring that students at an elementary school with Communities In Schools have access to services once they move up to middle and high school, Hance-Lehr said.

The organization currently operates in about one-fourth of the state’s Title I schools, which are those with a federal designation because of a high rate of students living in poverty.

Hance-Lehr said she wants the organization to be in every Title I school.

“We have a long way to go,” she said. “It won’t happen overnight.”

Mirroring a national trend

The recent growth in the number of schools served in Nevada mirrors trends within Communities In Schools’ national network.

From the beginning of the pandemic until now, the national organization — founded nearly 50 years ago — has grown from serving about 2,500 schools to more than 3,400.

It’s the fastest growth in the nonprofit’s history, said Rey Saldaña, president and CEO of the national Communities In Schools organization.

There’s a demand for growth in the post-pandemic world, said Saldaña, a Communities In Schools alumnus who received services while a student in San Antonio, Texas. He was in Las Vegas last month for a national Communities In Schools conference.

He said the Nevada organization has been a “bellwether” for the rest of the national network in getting into Title I schools in a sustainable way and also having a successful state budget appropriation.

In July, a bill-signing ceremony was held for Senate Bill 189 — known as the “Keeping Kids in School Act” — that appropriated $2 million in state funding for Communities In Schools of Nevada.

And earlier this month, the state organization announced that it received a five-year, nearly $11.9 million federal grant. It’s using the money to expand services at six campuses, including two in Clark County.

‘Good caring’

William Milliken, founder and vice chairman of the national Communities In Schools organization, said there’s a return on investment, but noted that the ultimate mission is all about relationships.

“Good caring creates good economics,” he said during an interview last month in Las Vegas.

Communities In Schools is not a charity — it’s a movement, Milliken said, and the philosophy is to provide wraparound supports for students.

It allows school principals to be freed up to be principals and teachers to be teachers, he said.

Alex Bybee, chief strategy officer for Communities In Schools of Nevada, said the scope of practice at schools has expanded from academics to also becoming a social services agency.

Communities In Schools aims to remove that pressure from educators, he said, which also improves working conditions.

The state organization works with about 120 partners to bring services into schools so families can more easily access them, said Palacios, who previously worked for the Clark County School District for 17 years.

And the organization is seeing results. Case-managed high school seniors in the Class of 2023 had a 95 percent statewide graduation rate. That’s higher than the overall state rate of more than 81 percent.

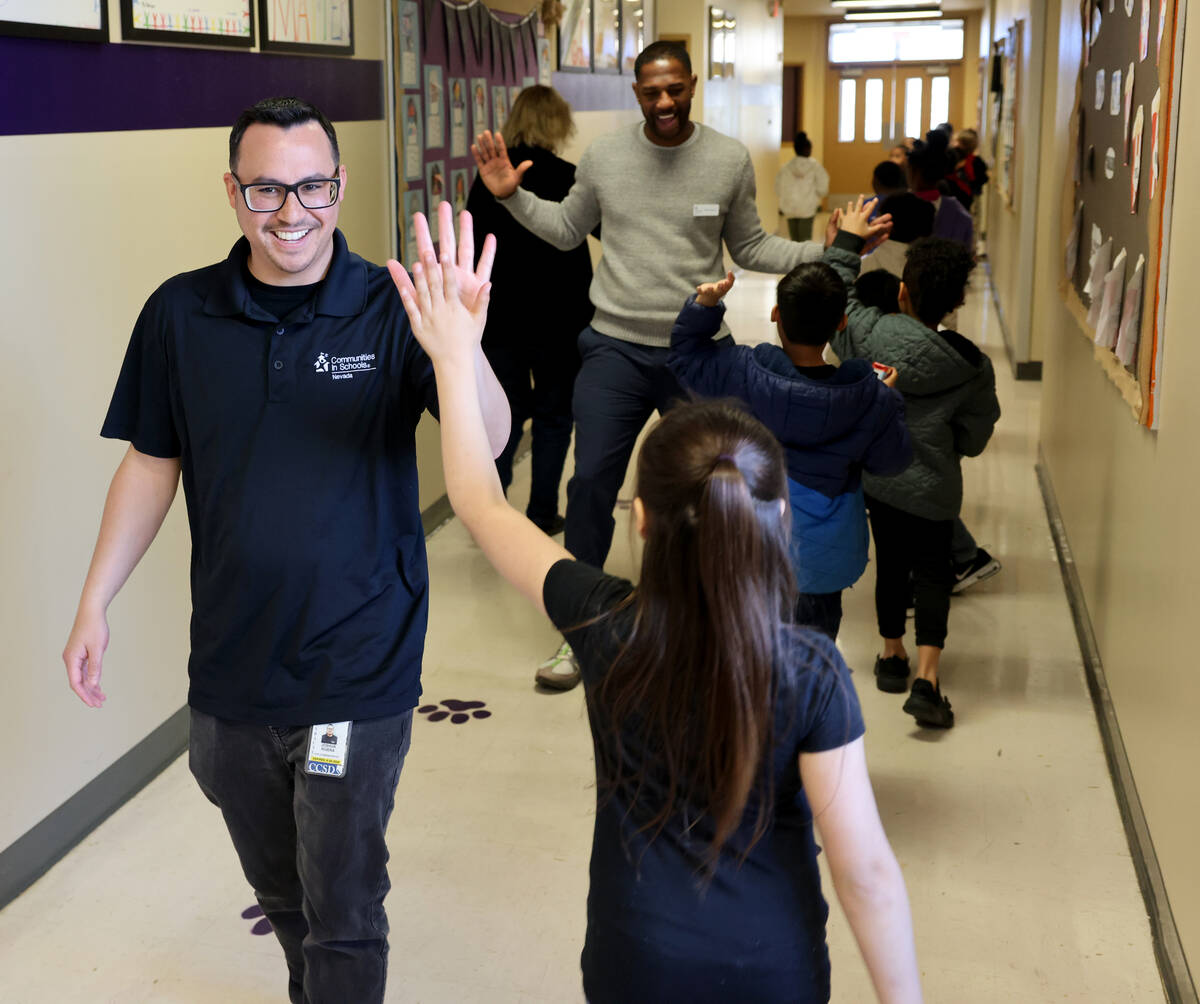

How the program works at Lowman Elementary

Typically, one Communities in Schools site coordinator is assigned at each participating elementary and middle school and two are placed at each high school.

But some schools have more. Lowman, for example, has two.

The school pays 40 to 60 percent of the cost and Communities In Schools fundraises for the remaining balance.

A site coordinator is one of the only people in a school building who don’t grade or punish students and that’s a “powerful place to be,” Hance-Lehr said.

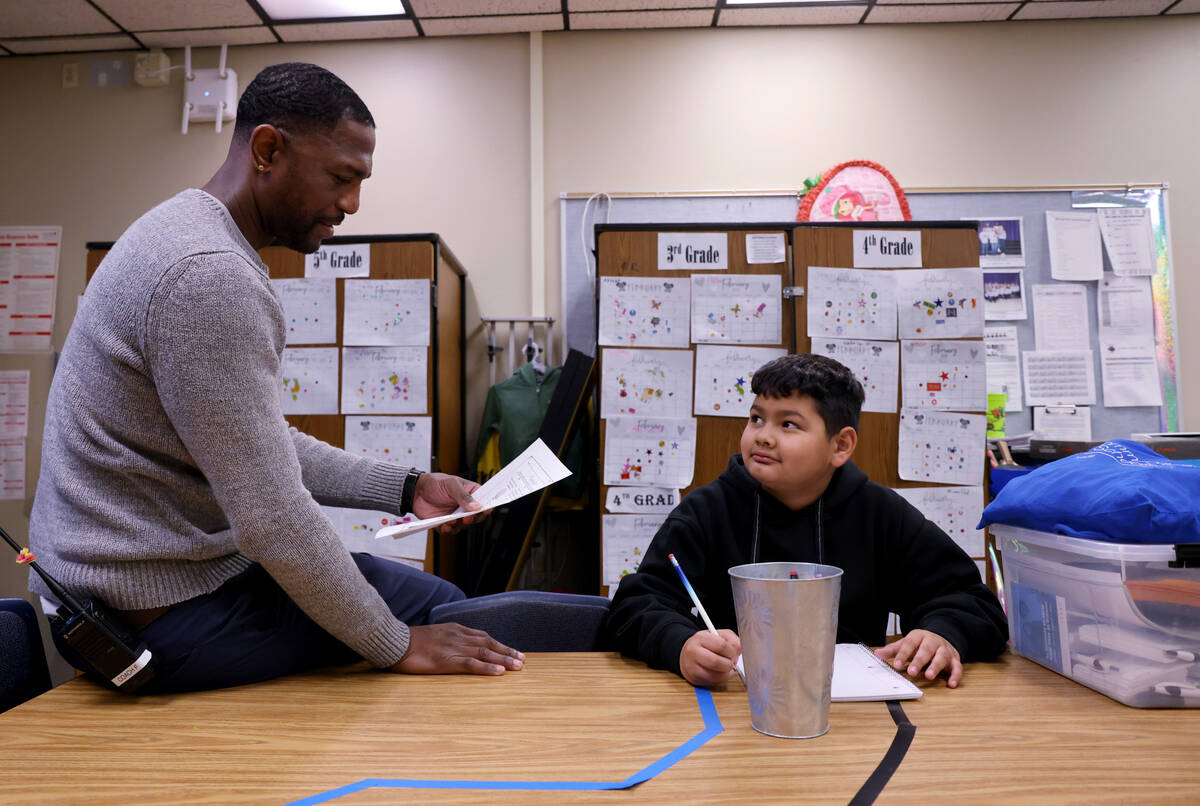

At Lowman, the nonprofit is addressing two main goals — to improve student attendance and behavior.

Last school year, only 8.9 percent of students demonstrated proficiency in math and 13.9 percent in reading.

Communities In Schools provides many resources, Lowman Principal Stephanie Tatman told visitors Tuesday.

The nonprofit helps students with needs such as conflict resolution and managing their emotions, Tatman said.

“Any resources that kids need, this is their go-to shop,” she said.

The organization works to address chronic absenteeism and provides incentives to students, Tatman said. And it runs a fifth grade barbecue at the end of the school year.

Every Friday at lunchtime, students can turn in “Lobo Bucks” — play money they earn for good behavior — for prizes. It’s a concept that Communities In Schools’ site coordinators proposed to school administrators.

Lowman also has Boys Town, a nonprofit organization that provides behavioral health services, on campus.

Tackling chronic absenteeism

Nearly 56 percent of Lowman students were considered chronically absent last school year. That means they missed 10 percent or more of school days.

That compares with 38.3 percent for the Clark County School District as a whole last school year.

Most Communities In Schools campuses are working on chronic absenteeism — one of the after-effects of the pandemic, Palacios said.

One in three children nationwide are considered chronically absent, Saldaña said,with factors at play such as a lack of transportation.

It’s a big topic and it’s being talked about in the context of not penalizing the child or family, he said, calling that change a “breath of fresh air.”

There’s an underlying story behind why a child misses so many school days, he said.

There are improved attendance rates on school campuses where there’s a Communities In Schools site coordinator, Saldaña said.

And when attendance is better, he said, that means more funding and stability in classrooms.

Challenges families are facing

In Nevada, the cost of housing is still a challenge, Hance-Lehr said. And when a family moves because their rent has increased, it may take a couple of weeks before their children get back into a school, she added.

A lack of child care is also a major issue and “older kids” — some as young as 10 years old — are staying home to watch younger siblings and are not able to go to school consistently, Hance-Lehr said.

It has always been a challenge, but it has gotten much bigger, she said.

Many students are also learning to be in an in-person environment again, and schools can be overwhelming — particularly for students who are dealing with trauma and situations at home, Hance-Lehr said.

The Clark County School District operated under 100 percent distance learning for about a year starting in spring 2020.

Another challenge is a lack of transportation. Students in the school district get bus transportation if they live more than 2 miles from their zoned school, Hance-Lehr said, but added that some neighborhoods are not safe to walk in.

She said there are some site coordinators who’ve started a “walking school bus” where they walk with a group of students to campus.

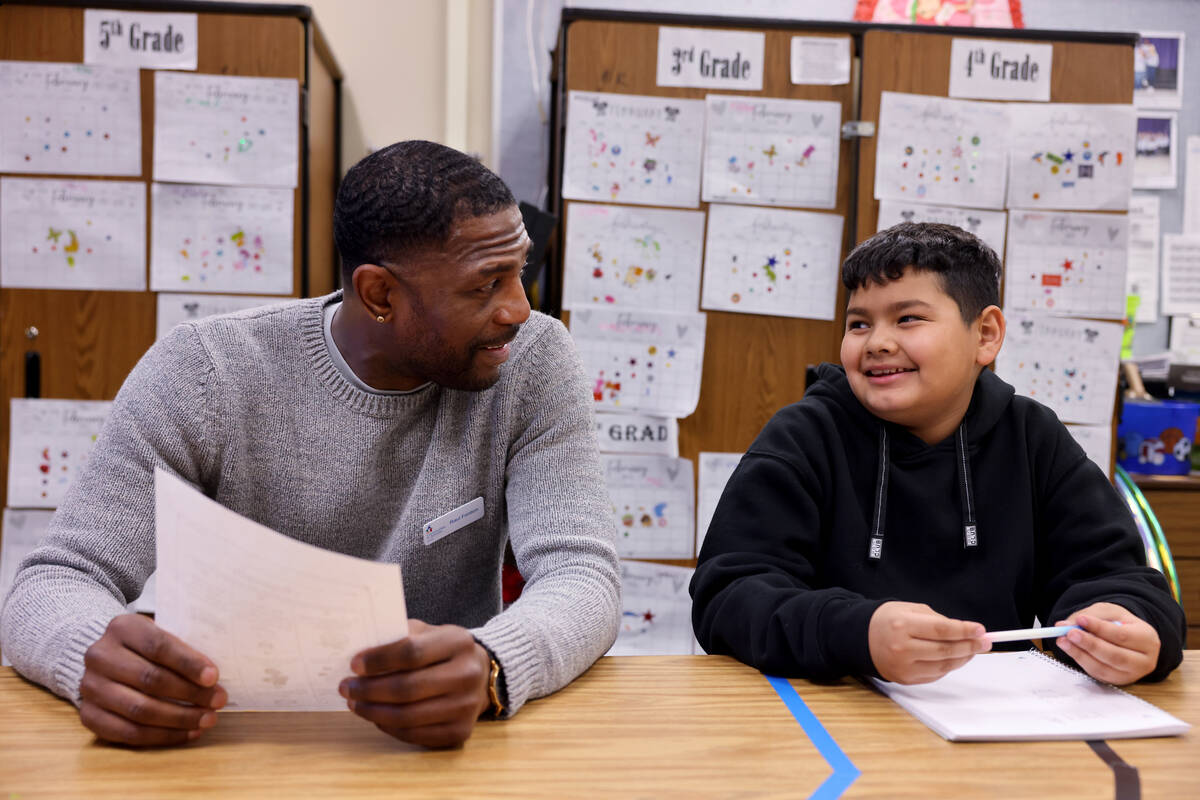

Back at Lowman Elementary, Freddie is finding support from the organization’s site coordinators and is seeing academic gains, too.

He recently won a regional school district award for having the most growth in reading. And he said he loves math and just found a new way to multiply numbers with three digits.

He said that Lowman’s site coordinators Joshua Rivera — who was recently promoted within the organization — and Raul Fention are “really good people.”

“I just want to thank them right now.”

Contact Julie Wootton-Greener at jgreener@reviewjournal.com. Follow @julieswootton on X.