‘Reorganized’ Clark County schools prepare for new year

Students at Bonanza High School will attend seven classes a day this year instead of six. The change is designed to give students more flexibility to take elective courses or catch up on credits.

It’s but one tangible example that the state-mandated reorganization of the Clark County School District — an effort to improve student performance by moving decision-making to the school level — is taking hold.

“If we had waited for the Clark County School District to meander through that behemoth process …” said Lisa Mayo-DeRiso, a parent and Bonanza organizational team member, her voice trailing off as she contemplated how long the change might have taken under the previous system. “We literally accomplished it in a couple months.”

That’s how the state-mandated reorganization is supposed to work: Schools control their budgets and work with school organizational teams to respond quickly to the needs of their communities.

It’s a stark change that advocates say the community has been clamoring after for years.

But as the massive reorganization of the nation’s fifth-largest school district moves from planning to implementation with the new school year beginning on Aug. 14, not everyone is convinced the internal remake will bring positive changes for the district’s 320,000 students and their families.

“I don’t know if the reorganization is going to do anything. I don’t know what the reorganization is supposed to be addressing,” said Denise Bolanos, a parent representative on the Doris French Elementary School organizational team. “Are we reorganizing the fat-cat spending on the upper end (the district administration), or are we reorganizing on the school-by-school level?”

Bolanos, who has two students at the school, said the principal there has always been transparent and open with parents, allowing them input into the process. She expects the school to continue to thrive under the reorganization, but she said she isn’t expecting any visible changes to be implemented right away.

A grand plan

Despite the grand intention of the 2015 law — and a follow-up law in 2017 — mandating the reorganization, elected officials say variances such as those between Bonanza and French are inevitable as schools and communities get a feel for the new rules.

“It depends on the school, and it depends on how well they’re implementing the reorganization,” said David Gardner, the former Republican assemblyman who sponsored the initial bill. “The idea is that you should be able to notice some things probably a couple days in.”

The path to reorganization hasn’t always been smooth. The school board sued over some concerns, which led to the second law solidifying the measure. The board then dropped the lawsuit, although trustees continue to voice concerns.

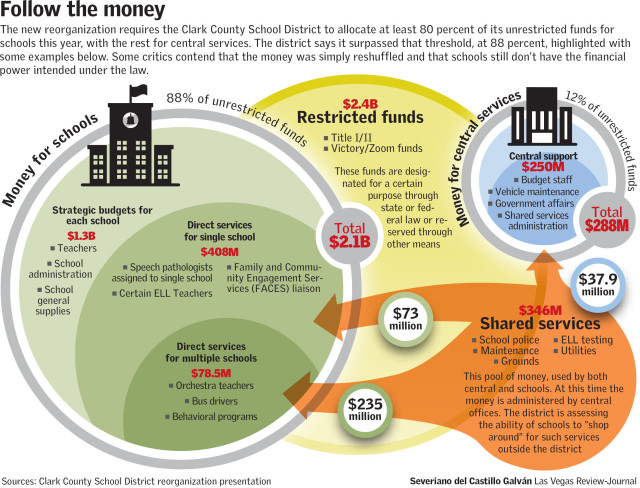

Now the district faces an estimated $45 million deficit that it is blaming, partly, on the costs of the reorganization.

And while the reorganization has been the subject of nearly two years of planning, discussion and debate, questions linger. We’ve answered some of them in an accompanying Q&A.

But here’s what’s going on in broad strokes.

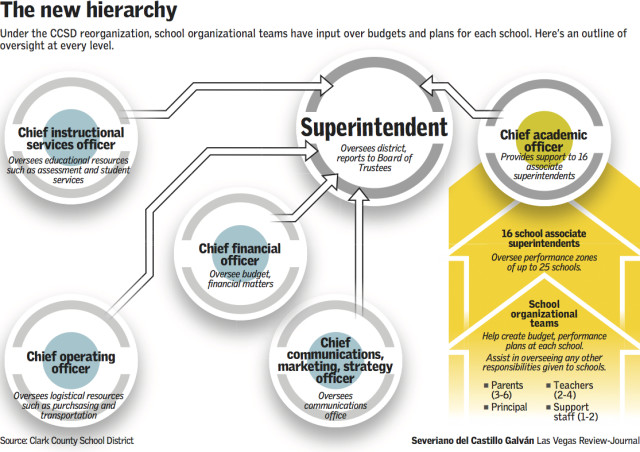

In essence, the district is being broken up into 356 single-school districts, with each school controlling the power and money to make certain decisions to best serve its students. Some services will still be provided by the district, but the bulk of the money will flow to the schools to do with as they see fit.

Calling the shots at the school level will be the school organizational teams, which include the principal, parents, support staff and teachers. They will decide on curriculum, special programs and other budgetary matters.

Associate Superintendent Kim Wooden said the reorganization is not a “one-size-fits-all approach,” and that’s why some schools may make obvious changes immediately and others may not.

“First and most important is the belief that decisions made closest to the school level will be the best decisions for the kids and the opportunities for parents to be more involved in that school’s decision-making,” she said.

Gardner, the former lawmaker, said that will require a culture change for educators, administrators and parents.

“It’s hard, in any field, to get people to think maybe there are better ways. In Nevada, we have to try and try whatever we can. We need to improve that if we’re going to help our students,” he said.

Parent concerns

Some parents who are happy with their schools aren’t clear why the reorganization was necessary or what it’s supposed to accomplish. Others aren’t sure what to expect.

“I don’t think we’re going to see a huge change at the beginning of the school year,” said Autumn Snyder of Henderson, parent of a student at Gibson Elementary School and two at McDoniel Elementary School.

Snyder said her main concern is being able to hold principals accountable, especially because two of her kids are special needs students with individualized education plans and she’s had issues getting school staff to comply with those plans in the past.

“I think the biggest changes are going to come when you have your daily interactions with the school,” she said. “For those of us that do, I think that’s going to be where our biggest issues arise. My concern is mainly checks and balances.”

Change can be both exciting and a little scary, according to parents who responded to an online survey conducted by the Las Vegas Review-Journal. Many expressed doubts that the reorganization will solve underlying problems in the system.

“Are things really going to be school-focused, or is the district going to continue to tell schools what to do?” one respondent asked.

“How is this going to improve the education our children receive so we are no longer last in the country?” another wanted to know.

Down the road

Experts who have studied similar efforts around the nation to empower principals and schools say change often happens slowly at first, as principals and organizational teams get a better feel for the best way to exert their authority and how much money they have to work with.

“We do see that over time that schools, once they start seeing the money as theirs, they do make spending decisions on the margins that free up money for things that are of greater value to them,” said Marguerite Roza, director of the Edunomics Lab at Georgetown University.

Gardner, the author of the reorganization legislation, expects a similar learning curve in Clark County, adding that district officials can facilitate the process and help schools succeed.

If they do, he said, that will create a ripple effect that will be felt throughout the state.

“If you fix Clark County and some of the issues we have down here, you’re more or less going to fix our state’s (poor education) ranking,” he said. “Where we go, the rest of the state goes. If we start really humming down here, everybody will be better.”

Contact Meghin Delaney at 702-383-0281 or mdelaney@reviewjournal.com. Follow @MeghinDelaney on Twitter. Contact Amelia Pak-Harvey at 702-383-4630 or apak-harvey@reviewjournal.com. Follow @AmeliaPakHarvey on Twitter.