Sex misconduct in CCSD is a system-wide crisis of broken trust

The Clark County School District didn’t fire Dailey Elementary teacher John Stalmach when he was arrested in 2012 for having sex with a 16-year-old Basic High School student.

Instead, the district offered him a settlement: In exchange for his resignation, the incident wouldn’t be documented in his personnel file.

It wasn’t the first time Stalmach had faced allegations of inappropriate behavior.

An untold number of Clark County staff members have had their personnel files scrubbed of sexual misconduct allegations, creating a culture that allows sexual behavior between students and teachers to fester.

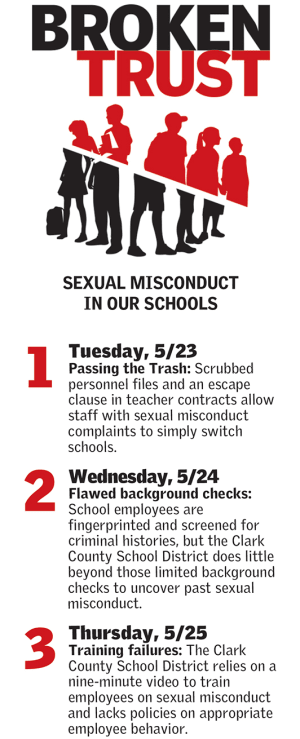

It’s just one part of a system-wide crisis of broken trust that, according to lawyers and experts, stems predominantly from three issues: the district’s contract with the teachers’ union, loopholes in background checks and insufficient employee training.

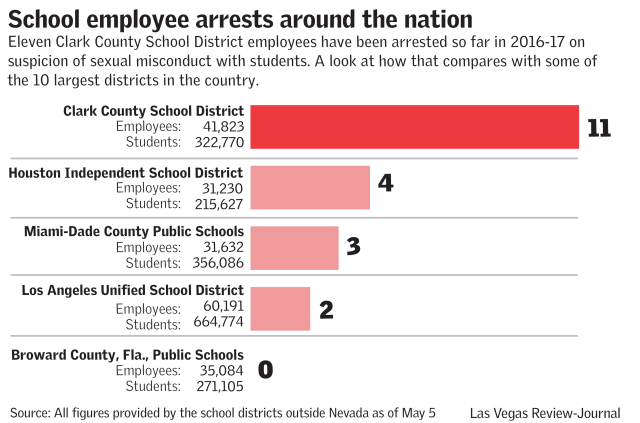

Over the past three years, 31 staff members have been arrested on suspicion of sexual misconduct or inappropriate behavior with a student. Since July, there have been 11 arrests.

That’s higher than the number of such arrests for the 2016-17 school year in some of the nation’s largest districts. The Los Angeles Unified School District, the second largest system in the country, reported just two.

Suspects in two of this school year’s 11 arrests had a known history of inappropriate behavior, according to police records, but were allowed to remain in schools — a practice known as “passing the trash.”

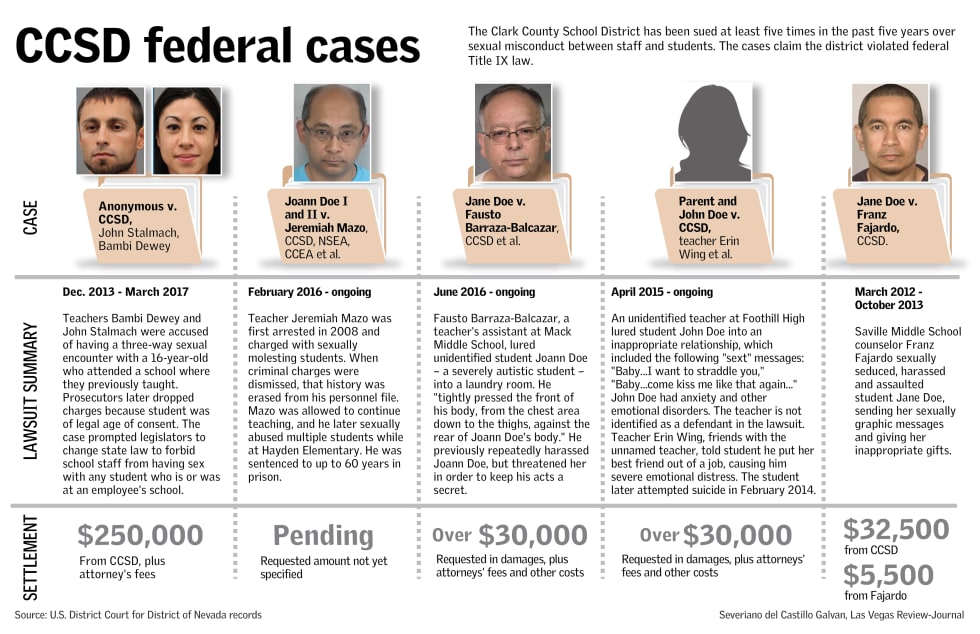

What’s more, the district has faced at least five federal lawsuits over sexual misconduct between staff members and students in the past five years — three of which are ongoing. Two of those cases document clear instances of the system passing off problematic teachers from one school to another. All five initially claimed the district violated the rights of the victims under Title IX, although at least one has since dropped that claim.

And all of those cases originally argued the district knew or should have known about staff misconduct, but did little — if anything at all — to stop it.

“You have students who’ve been molested at 8 or 9 years old that will never trust their teachers again,” said Robert Eglet, an attorney for a number of families in a passing-the-trash case involving former teacher Jeremiah Mazo.

‘Safe haven’ for pedophiles

This year, teacher Jeffrey Schultz and custodian Jesus Acosta are the latest examples of the district’s failure to keep staff with known histories of misconduct away from children.

But the breakdown of whatever safeguards exist to protect students started long ago, in part because of the power of the unions that protect employees no matter the allegations against them, according to attorneys involved in the federal lawsuits.

If a teacher is cleared of a criminal or civil charge, “all written reports, comments or reprimands concerning actions which the courts found not to have occurred, shall be removed from the teacher’s personnel file,” according to the Clark County Education Association contract.

It’s that clause, Eglet says, that creates a “safe haven” for pedophile teachers in Clark County.

“You may as well put an ad … that says, ‘Hey … pedophile teachers, come to Las Vegas to teach, because unless you’re proven guilty beyond a reasonable doubt, your record will be sealed,’” Eglet said.

That’s exactly what happened in the case of Mazo, according to Eglet’s lawsuit. In 2008, Mazo was arrested on suspicion of sexually molesting students at Simmons Elementary.

But when the charges were dismissed, the allegations were removed from his personnel file and he continued teaching at other schools in Clark County, according to an amended complaint filed March 1.

Instead of firing Mazo or reassigning him to a job where he had no contact with children, the district transferred him to other schools, including Hayden Elementary, where he was again accused of sexually molesting students. Mazo pleaded guilty to three felony counts of attempted lewdness with a child in August 2015 and is serving up to 60 years in prison.

The CCEA and the Nevada State Education Association are defendants in the lawsuit, which claims the unions assisted in the dismissal of Mazo’s 2008 charges.

“To not realize the consequences of this was beyond negligent — it’s gross negligence,” Eglet said. “The school district and the union both share responsibility for this happening.”

John Vellardita, the executive director of the Clark County Education Association, stands behind the clause in the contract.

“We represent 18,000 licensed professionals, and there’s 320,000 kids and there’s a lot of unfounded accusations that fly back and forth,” he said. “And without a due process that tries to essentially determine what’s fact from non-fact, anything that’s placed in anybody’s file that’s not based on any kind of findings of evidence shouldn’t be there.”

Vellardita stressed that the union does not condone or protect, in any way, any educator engaged in any criminal act.

“We don’t want folks that engage in criminal behavior in these classrooms or around kids, bottom line,” he said.

Still, the contract also allows teachers to request the removal of reports or reprimands from their personnel file that are beyond three years and one day old.

John George, the attorney for Mazo, said he has seen allegations of impropriety with children in his family law experience, noting that in parenting disputes or divorce, somebody can make an allegation that is completely unfounded.

“Generally, if an investigation is taking place and they find that these allegations are unfounded, then why would you allow these allegations to negatively impact somebody’s life?” he said. “Simply making an allegation like that can literally ruin somebody’s life.”

But he added that nothing is wrong with adding extra layers of protection in sexual misconduct cases.

He declined to comment on the Mazo case specifically.

Litigation fears

When it comes to firing a problematic staff member — whether teacher, support staff or administrator — district leaders’ fears of costly arbitration proceedings and wrongful termination lawsuits play a role in the problem.

“My sense of it is, that’s a principle component in the manner in which these cases are not aggressively pursued,” said attorney Don Campbell, who represented the victim in the Stalmach case. “That they feel that the unions have too much power or they have too much money or they’ll throw too much shade at them through litigation.”

Clark County School District Superintendent Pat Skorkowsky acknowledged that arbitration and litigation costs quickly add up.

“We have to make sure that we are handling it appropriately so that we would always prevail in those situations,” he said.

Stalmach and another teacher, Bambi Dewey, were accused of having sex with a 16-year-old student in 2012. Yet the district had previously investigated Stalmach for inappropriate text messaging with a female student at his prior school, Basic High, around 2009.

After that 2009 investigation, both the Basic High principal and the director of employee management relations recommended Stalmach’s termination over concerns with his behavior, Campbell’s lawsuit uncovered.

“He absolutely cannot come back to my school,” Principal David Bechtel told the district, according to the lawsuit.

But the district’s general counsel did not fire Stalmach to avoid the arbitration that would have occurred if Stalmach appealed the decision, according to the lawsuit. Stalmach stayed in the district, and he was arrested after the encounter with the 16-year-old about three years later.

When prosecutors dropped the charges in that case, the district approved the settlement agreement with Stalmach to get rid of him. Stalmach, who now lives in Colorado, still has a valid teaching license in Nevada that expires in July 2018, according to the state Department of Education. Dewey’s license expired in 2013.

Skorkowsky said it’s important to look at the union contract to see what can be done to strengthen the district’s policies.

If there are situations that don’t warrant any legal or disciplinary action, he said, then the district doesn’t necessarily have control over what goes in that personnel file.

“We might have the best teacher in the world who has somebody who comes out and says that this happened, and there is nothing ever found in the investigation,” he said. “So it is very difficult. It’s a thin line trying to protect the teacher as well as to protect the students.”

Present-day problems

It took one upset father and a phone call to the police to bring the prior history of Brown Academy teacher Jeffrey Schultz to light.

Chad Jensen said he wasn’t happy with the answers he got from a school official after being told that his 13-year-old daughter reported an uncomfortable conversation with Schultz.

“She told me that she couldn’t reveal any information, that they’re going to be looking into it, that nothing’s going to be done today about it,” he said. “I said, ‘Well, if you guys aren’t going to do nothing about it, I am.’”

So he went outside and called police.

Jensen subsequently found out that Schultz had faced previous allegations of misconduct at Brown Academy and another school. Schultz now faces three counts of annoyance, molestation of, or indecency toward a minor younger than 18. He’s on paid suspension from the district pending the superintendent’s letter of dismissal.

About three months later, Jensen said he received another phone call from the school: His 11-year-old daughter reported that a substitute teacher touched her thigh. Henderson police confirmed the matter was being investigated, but no arrest had been made in the case as of Monday.

Jensen’s older daughter, Kendra, said she and two friends felt uncomfortable after Schultz asked them what kind of underwear they wear beneath their leggings.

They filed a report in the front office later that day, she said, in part because they remembered that their friend previously switched out of Schultz’s class. That friend felt uncomfortable when Schultz touched her shoulder.

“It was just going through our heads … how he did that to her,” she said, “that we didn’t want anything further to happen to us.”

Jesus Acosta, a custodian at Tarkanian Middle School, was warned to correct his behavior with students before he was arrested.

District police had previously investigated email and text conversations Acosta had with students in June 2016, according to police records. He was told to refrain from sharing personal contact information with students and keep his interactions with them professional. He kept his job at the school.

This year, three sixth-grade girls at the school reported that Acosta had hugged or kissed them and made inappropriate comments that left them uncomfortable. Acosta was arrested and charged with three counts of unlawful contact with a minor under 14 years of age.

At a School Board meeting in May, Kendra’s grandmother, Rhoda Jensen, issued a plea to trustees.

“It’s got to stop. These are 11-, 12- and 13-year-old students that now do not trust their teachers, their principals, their counselors,” she said. “They’re not sure who to trust.”

Violation of federal Title IX law

The Clark County School District’s acquiescence to an escape clause in its contract with the teachers’ union has put the system in direct violation of Title IX, according to an attorney with expertise in the federal law.

“All the attention is around campus rape at the university level, but really K-12 is a much worse landscape than what we see in college campuses,” said John Clune, a Colorado attorney who has litigated a number of high-profile Title IX cases across the country.

Passed in 1972, Title IX prohibits discrimination on the basis of sex in education programs that receive federal funding. The law also covers acts of sexual harassment and prohibited sexual conduct.

But the school district’s contract with the Clark County Education Association stipulates that “all written reports, comments or reprimands concerning actions which the courts found not to have occurred, shall be removed from the teacher’s personnel file.”

Clune said the clause in the contract clearly puts the district in violation of federal law.

“Schools have a contract with the federal government. … Clauses in union contracts, none of that alleviates the school’s responsibility under Title IX,” Clune said.

Still, Superintendent Pat Skorkowsky believes the district must follow the language in the union contract. He said the clause doesn’t conflict with Title IX.

“If there was not enough information for us to be able to see charges filed in a jurisdiction, then it’s difficult for us to fire a teacher if no charges were filed,” he said. “It makes it very difficult.”

But Skorkowsky acknowledged that “it is time for us to revisit that and look at special circumstances, and that’s something that’ll have to be done through negotiations.”

Clune called such scenarios a campus safety issue and suggested that public school systems ignore such clauses or stop negotiating them in the first place.

“The school has an obligation to do their own investigation,” Clune said. “The Department of Education is very clear. Investigations have to be done independently. This has nothing to do with whether the case ends up going to court or not.”

Title IX cases, Clune said, require “preponderance of evidence” as a burden of proof — lower than the “beyond a reasonable doubt” standard in the teachers’ union contract. Each of the five federal lawsuits against the district in the past five years have claimed violations of Title IX; two have been settled, three remain ongoing.

“What happens in so many situations is that schools do not take the time and they don’t want to spend the money to develop strong policies,” Clune said. “And then they end up spending tenfold that on civil liability (for) lawsuits and their own kids getting hurt.”

Schools found in violation of Title IX risk losing federal funding. But no K-12 school has ever had funding pulled due to violations, according to the U.S. Department of Education.

The district was previously found in violation of Title IX in December for its mishandling of a special education student’s harassment complaints. The U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights ordered employees at the child’s school to undergo Title IX training, among other corrective actions.

The law also requires that a qualified, full-time Title IX compliance officer clearly be designated. But the district’s coordinator isn’t easily identified.

Susan Smith, listed as an assistant superintendent in the district’s administrative telephone directory, was designated the Title IX coordinator in December. Yet a district spokeswoman previously identified Interim Chief Instructional Services Officer Billie Rayford as the Title IX officer.

Online, the district’s website still says the “chief educational opportunity officer” is the acting Title IX coordinator.

The district has had a Title IX coordinator since 2015, a spokeswoman said recently, and a staff member has been selected as the next coordinator. That employee is currently in training.

Contact Amelia Pak-Harvey at apak-harvey@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-4630. Follow @AmeliaPakHarvey on Twitter. Contact Meghin Delaney at mdelaney@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0281. Follow @MeghinDelaney on Twitter.