Tracking the Clark County school sexual misconduct cases

The rash of arrests of Clark County teachers and employees on sexual misconduct charges sparked big headlines when the trend emerged last year and helped prompt stronger school district policies and new state laws.

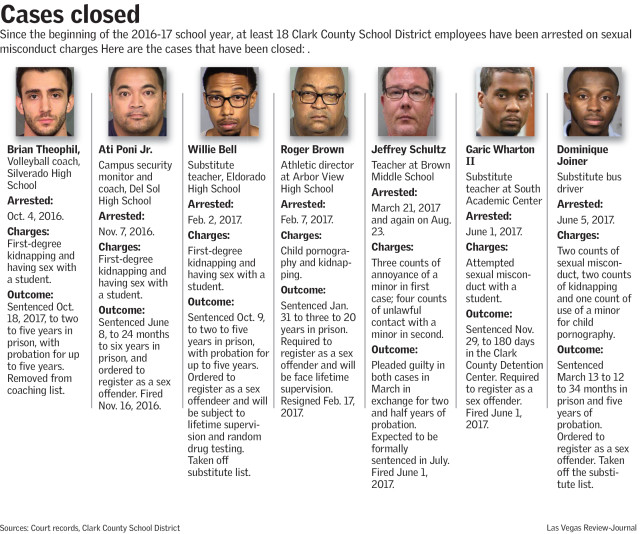

But after the initial eruption of shock and anger, the cases of each of the 18 Clark County employees arrested on such charges since July 1, 2016 have faded into the background as they ground through the criminal justice system.

A year after the initial peak of arrests in March 2017 — when four school district employees were arrested, some just days apart — the Review-Journal revisited the cases to see how many have led to convictions and what punishment the offenders have received.

Many of the cases are still moving through the court system, but seven of the 18 have come to a close. Of those, most of the sentences included jail time — up to 20 years in one case — and all but one of the perpetrators will be required to register as sex offenders, a penalty that will follow them the rest of their lives.

Registering as a sex offender is a great step to keep the former employees from working around students again, said Terri Miller, president of SESAME, a national nonprofit focused on stopping educator sexual abuse, misconduct and exploitation. But she believes those convicted should have received more jail time.

“These children’s lives that they have offended have been irrevocably changed forever,” she said. “The children are sentenced to a lifetime of coping, so it stands to reason that those who caused that trauma, that lifelong trauma, should receive stiffer penalties.”

A questing of timing

The review of cases that spurred the Review-Journal’s Broken Trust special report documenting the district’s sexual misconduct problem and examining the causes also uncovered one arrest that has not yet resulted in charges.

Michael Barnson, a former volunteer coach at Cimarron-Memorial High School, was arrested more than a year ago on allegations of having a sexual relationship with a 17-year-old student. He was arrested after his wife found pictures on his phone, according to a Metropolitan Police Department arrest report last March. According to the arrest report, Barnson admitted having sex with the student twice.

But as of this week, the district attorney’s office was still reviewing the case, and won’t explain why it’s taken so long.

“This matter is under final review by the district attorney’s office and a decision to prosecute, or not, will be made in the next seven to ten days,” officials said in a statement on Thursday.

Barnson could not be reached for comment by the Review-Journal and it’s unclear whether he’s retained an attorney, since no court filings exist yet.

Click image to enlarge

In the cases that have been brought to a conclusion, most took about six months from arrest to sentencing, though two took nearly a year.

But occasionally the justice system has moved more swiftly.

The case against Garic Wharton II, who was arrested June 1 on one charge of attempted sexual conduct between a school employee and a student, took just five months.

The substitute teacher at South Academic Center was accused of use Snapchat, a social media platform, to communicate sexually explicit messages with a student. In November, he was sentenced to 180 days in the Clark County Detention Center and ordered to register as a sex offender.

Five employees have been arrested on sexual misconduct charges during the current school year, and one employee, teacher Jeffrey Schultz, who was initially arrested last year, was rearrested on new charges. All of those court cases except for Schultz’s are still working their way through the system.

Making a deal

Despite passing a polygraph test, according to his attorney, and maintaining his innocence, Schultz entered what is known as an Alford plea recently to end his case. An Alford plea is treated as a guilty plea by the court, though the defendant does not admit to the criminal act and asserts his or her innocence.

Schultz, a former science teacher at Brown Middle School in Henderson, was arrested in March 2017 on three misdemeanor counts of annoyance, molestation of or indecency toward a minor younger than 18.

In August, Schultz was arrested on four new counts of unlawful contact with a minor, a gross misdemeanor, after more students came forward with complaints about his behavior.

Schultz has maintained his innocence and passed a lie detector test administered by Ron Slay, tje state’s preeminent polygraph expert, said Chris Rasmussen, Schultz’s lawyer. Despite that, Schultz was nervous about facing a jury and the possible sentence of 10 years to life.

“He doesn’t want to face a jury and get convicted and basically die in prison,” he said.

Schultz is scheduled to be sentenced in July and the terms of his deal both parties agreed to include two and a half years of probation, in which he’ll have to register as a sex offender. The case took about a year from the initial arrest, which Rasmussen said was pretty normal.

Schultz appears to be the only employee who settled his case with an Alford plea.

License revocations

So far, none of the arrested employees who had licenses issued by the state Department of Education has had their licenses revoked, meaning they technically could be hired to teach again.

The state license revocation process typically starts after a conviction, spokesman Greg Bortolin said. The department will request certified copies of the conviction records, which take a few weeks and then the state superintendent of instruction can start the process to revoke the license.

That’s another area worth exploration, Miller said. She said she wold like to see more automatic triggers to help the department track cases and act quickly upon convictions faster.

Contact Meghin Delaney at 702-383-0281 or mdelaney@reviewjournal.com. Follow @MeghinDelaney on Twitter.