Why do so many charter schools want to open in Nevada?

A Salt Lake City-area public charter school with two campuses is ready to expand and has an eye on Las Vegas.

“Our organization got to the point where we could serve more kids,” said Anthony Sudweeks, founder and executive director of Wallace Stegner Academy.

One of the reasons for considering Las Vegas: The downtown area is home to several one- and two-star elementary and middle schools, Sudweeks said, and few charter school options.

Wallace Stegner Academy isn’t alone in wanting to open a charter school in Nevada. It’s among 44 groups that have submitted a letter of intent this year with the Nevada State Public Charter School Authority. That is up from 27 letters of intent in 2020, according to data released by the authority in early May in response to a Review-Journal inquiry.

So why are so many groups interested in opening a charter school in Nevada, and particularly in the Las Vegas Valley? The charter authority’s top leader says she’s not sure there is a trend at this point, but some groups who submitted a letter of intent may be looking at the area’s population growth or are moving forward after delaying plans because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

As for out-of-state charter school networks that are interested in coming to Nevada, charter authority Executive Director Rebecca Feiden said, “I think some of that has to do with demographics.” Las Vegas has a growing population base, and that “makes it more operationally interesting to folks.”

Sudweeks said he’s not sure why the charter school authority is getting a lot of interest this year, but “downtown (Las Vegas) might be more of an open market for these charter operators.”

He noted that many Las Vegas Valley charter schools are in suburbs that already have access to high-quality Clark County School District campuses.

That doesn’t mean it’s easy to get approval to open. Sudweeks said he has noticed both in Utah and Nevada that “the process for opening a charter school has become much more difficult.”

No cap on new schools

The state charter authority has two deadlines each year, Jan. 15 and July 15, for new school applications. Applicants also must first submit a letter of intent.

The notices are nonbinding, meaning people who submit one aren’t required to turn in an application. And typically, only about 20 to 30 percent of those who submit a letter of intent follow through with a completed application, Feiden said.

Last year, the authority received 27 letters of intent. Only seven of those groups submitted an application, and four were approved.

Since 2016, the number of new Nevada public charter schools — which receive state funding and are free for students to attend — has ranged from zero to five each year.

There is no cap on how many new schools the charter authority can approve annually. Some critics are concerned about rapid charter school growth in Nevada — particularly, that campuses are drawing students and funding away from traditional school districts.

The Clark County School District has seen an enrollment drop for a few years, including during the COVID-19 pandemic. During the pandemic, distance learning was underway for about a year before students had the option of returning to campuses this spring.

In an emailed statement last week in response to a Review-Journal inquiry, the school district — which has more than 300,000 students — didn’t directly address charter school growth and instead promoted its own offerings.

“The Clark County School District is proud to provide our families with school choice including the option to attend zoned schools, magnet programs and the Nevada Learning Academy,” the district said.

Managing growth

In 1997, the state Legislature authorized the creation of public charter schools. The Nevada State Public Charter School Authority was created in 2011, initially with responsibility for 16 campuses previously overseen by the Nevada State Board of Education.

Now, the charter authority oversees 67 school campuses and more than 53,000 students.

During the 2019 state legislative session, a bill was floated seeking a moratorium on new charter schools until this year.

It was amended to include no restrictions on new campuses and later passed. Instead, it requires the charter authority to have a growth management plan.

The Nevada State Education Association, a statewide teachers union, supported the 2019 bill as it was originally written. In an April 2019 memo posted on its website, the union said charter schools have grown dramatically over the years “to include large numbers of charters that are privately managed, largely unaccountable, and not transparent as to their operations or performance.

“The explosive growth of charters has been driven, in part, by deliberate and well-funded efforts to ensure that charters are exempt from the basic safeguards and standards that apply to public schools,” the union wrote. “This growth has undermined local public schools and communities, without producing any overall increase in student learning and growth.”

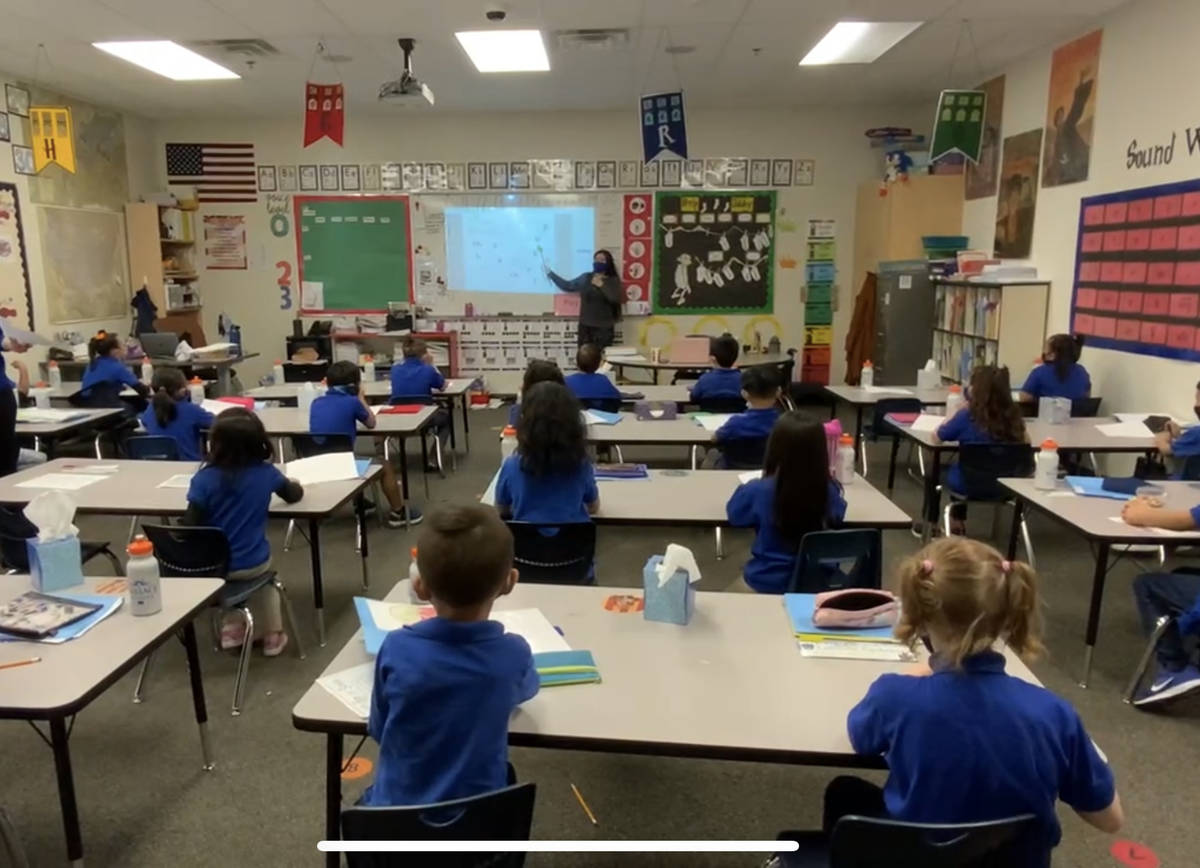

To win approval from the charter authority, a school must demonstrate an academic or demographic need. That would include such things as helping students who qualify for free or reduced-price school lunches, English language learners or students who have disabilities; geographic areas where a large number of students attend a one- or two-star school; or students who are at risk of dropping out of school.

The charter authority’s growth management plan, revised every two years, includes information about charter school demographics compared with other public schools in the state.

More than 60 percent of authority-sponsored charter schools had a four-star or higher rating on a five-point scale during the 2018-19 school year — the most recent star ratings issued by the state, according to this year’s growth management plan.

But compared with other public schools, they have fewer students who qualify for free and reduced-price school lunches — 39.4 percent versus 72.5 percent for Nevada public schools — who are English language learners — 7.7 percent versus 13.3 percent — or have an Individualized Education Program, 9.5 percent versus 12.4 percent.

The charter authority “serves a lower percentage of students in these three student groups, all of which have been historically underserved, but has seen steady increases in these student populations over the past three years,” according to the plan.

Uptick in letters of intent

For the summer application cycle, the state charter authority received 29 letters of intent. All but one of those schools want to open in Clark County, and the majority are aiming for the 2022-23 school year.

The number of letters of intent has fluctuated since 2016, but this year has seen the most. There was also a large jump from 12 letters in 2017 to 37 in 2018.

“This number tends to ebb and flow,” Feiden said. She has already heard from “a number of folks” who submitted a letter of intent this year but don’t plan to turn in a new school application.

Some groups who submitted a letter of intent this year have in a previous year, too. And some have been in communication with the charter authority for a while, Feiden said.

Is there more interest in opening a charter school due to worries of a future moratorium on new charter schools in Nevada? “I really haven’t heard that concept at all,” Feiden said.

The bigger thing the charter authority is seeing, she said, is more new school proposals that align with the state’s goal of making sure “our schools are helping close opportunity gaps and address historical inequities.”

Pushing to expand to Las Vegas

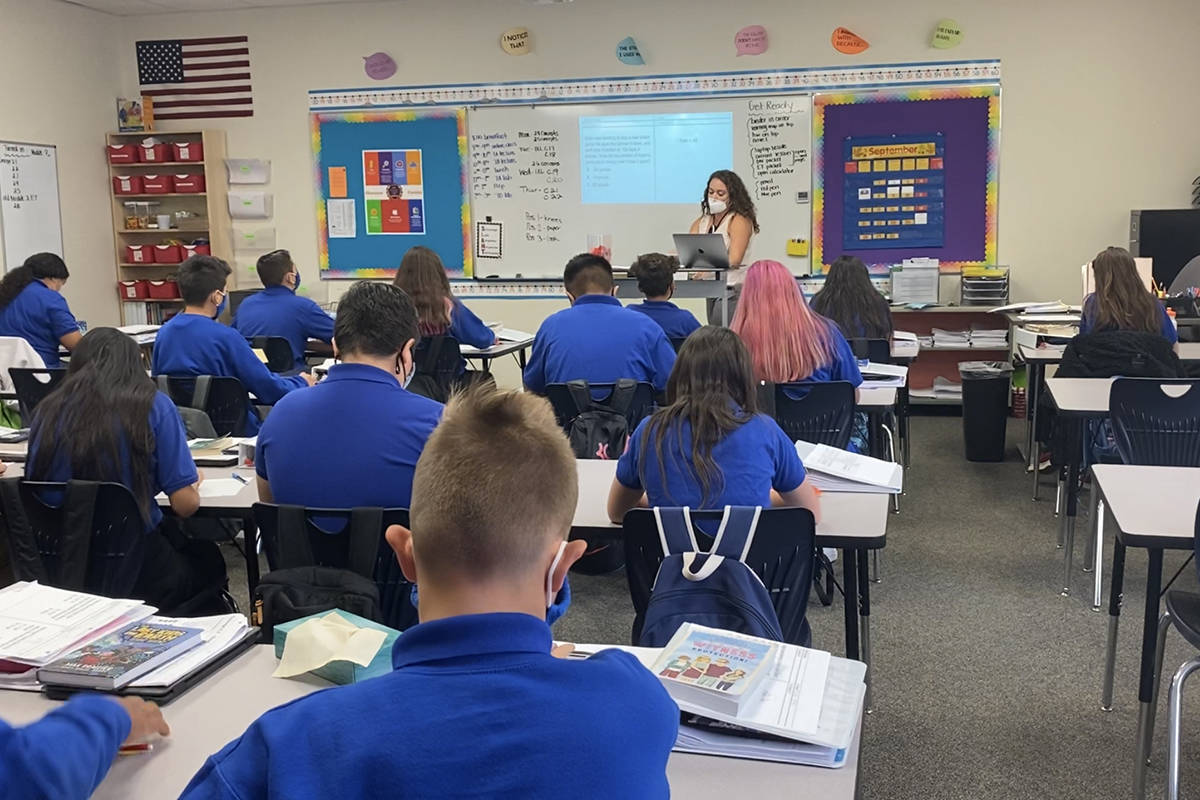

Wallace Stegner Academy has about 1,200 students at its Salt Lake City-area campuses. Now, it wants to open a Las Vegas campus during the 2022-23 school year.

The school’s goal is to serve 988 Las Vegas students in kindergarten through eighth grades.

One major reason Wallace Stegner Academy is looking at Las Vegas is its geographic proximity to the Salt Lake City area, Sudweeks said, and the school also works with some companies that do business both in Utah and Nevada.

Wallace Stegner Academy’s main campus in downtown Salt Lake City is surrounded by low-performing schools, Sudweeks said. Almost 90 percent of students qualify for free or reduced-price school lunches and the student body is almost entirely children of color, he added.

Some schools lower the bar academically for students who attend low-income schools, Sudweeks said, referring to the concept as “the tyranny of low expectations.”

“We know our students come to us much lower than they should be,” he said. If the school’s mindset is that’s all they’re going to accomplish, “we would be just like the schools around us.”

Contact Julie Wootton-Greener at jgreener@reviewjournal.com or 702-387-2921. Follow @julieswootton on Twitter.