Henderson plant helped launch Las Vegas Valley’s multiracial evolution

When the United States entered World War II in 1941, word about new defense-related job opportunities in the Las Vegas Valley was already traveling fast through black communities in the South.

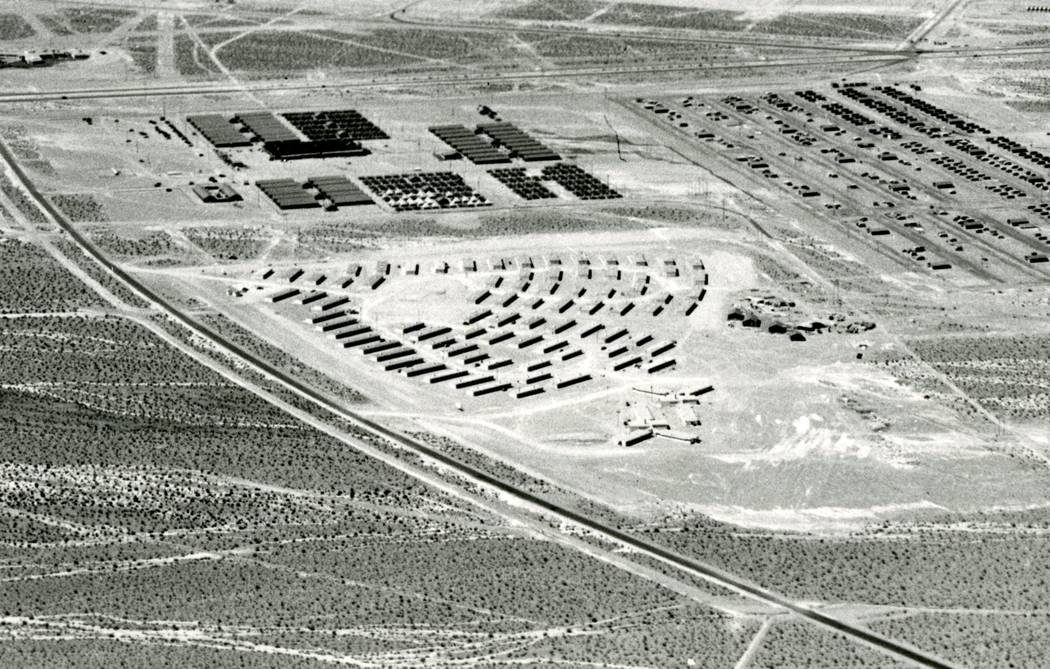

The main magnet was the Basic Magnesium Inc. plant in Henderson, which opened earlier that year and eventually churned out one-fourth of the magnesium used by the War Department for incendiary munition casings and aircraft parts.

The pay was far greater than the menial jobs available in places like Fordyce, Arkansas, where most black men worked at a small local lumber company and black women spent their time working as maids or taking odd jobs.

So just as Midwesterners fled the parched Dust Bowl in the 1930s, they packed their cars and headed west to Las Vegas, beginning the multiracial transformation of Southern Nevada that continues to this day.

U.S. census data shows that the number of nonwhite workers in Nevada nearly doubled from 1940 to 1950, then continued to rise as casinos added new opportunities for black workers.

“That part of the migration I sometimes refer to as ‘the great migration,’” said Claytee White, director of the Oral History Research Center at UNLV Libraries. “It was spurred by BMI and all the jobs that were available, just like the Hoover Dam did for white Americans.”

The government built two housing complexes in present-day Henderson for those working at the plant: Victory Village, where whites lived, and Carver Park, for blacks.

Carver Park consisted of 64 dorm units, 104 one-bedroom units, 104 two-bedroom units and 52 three-bedroom units and was designed by black architect Paul Revere Williams. It included a Catholic hospital, a school, two grocery stores, laundry facilities and a recreational center.

But the tract wasn’t completed until 1943, by which time many of the newly arrived black workers already had settled into mostly substandard housing in the area now known as the Historic Westside.

“That’s where the churches were, that’s where the culture was centered,” White said. “You would have to go to the Westside for any kind of community events, spiritual meetings, dancing or restaurants.”

Ultimately, only 40 black people moved into the flat-roofed, cinder-block units at Carver Park, White said, and the rest of the homes were filled by white families.

Flocking from Fordyce

The newly arrived Southerners, most of them from Arkansas, Louisiana and Mississippi, didn’t forget their roots, though. The migrants from Fordyce formed The Fordyce Club of Las Vegas, which this week celebrated its 41st year of existence.

“We came here for better living,” said Inez Harper, the group’s assistant treasurer, “(and) we wanted to find a way to reunite ourselves.”

At a Sunday celebration at the New Revelation Baptist Church in Las Vegas, the women wore wide-brimmed hats, the men wore suits, and the next generation bounced along to booming music of praise.

“We want to reap what we have sown,” club member Patricia Feaster said.

Many of the club members or their relatives were originally recruited by the late Jimmy Gay, a black hotel executive who later established the first youth recreational activities in the area for black children. He was also the state’s first black mortician.

The Rev. D. Edward Chaney emphasized the group’s faith and asserted that they were “standing on the promises of God” when they abandoned their homes for the desert.

“We thank God for those who sought fit, many years ago, in the movement to the West,” he said. “Thank God for the life we’ve made.”

Opportunity and oppression

While Fordyce sent an especially large number of its residents, black workers from all over came to see if the valley might be the answer to their American dreams.

Among them was the late Woodrow Wilson, who traveled from Morton, Mississippi, in 1942 and went on to become the first African-American elected to the Nevada Assembly in 1966.

But the late Otis Harris left east Texas in the early 1940s, where he worked inconsistent, cheap labor jobs, not only for economic opportunity, family members recall.

He got word through the grapevine that he was about to be lynched for talking back to his white boss.

“He sassed back to one of the bosses, and he got the word that they were going to string him up, and he got out,” said his eldest son, Otis Harris Jr., 77. “Then, he sent for us.”

Harris Sr. was originally headed to California but stopped in Las Vegas and heard they were hiring at the plant in Henderson.

A year later, he had saved enough money to send for his family, which then consisted of his wife and six children, all of whom made the trip packed into a “rickety” old car.

Harris Jr. was just 1 at the time, but he remembers his parents retelling stories of the cowboy town of Marshall, Texas, where they previously lived.

“They couldn’t survive there,” he said. “Here, they could work at the plant.”

Harris Jr. grew up in the Historic Westside, while their father worked at the plant before leaving to work in the casinos.

At home, he remembers, he and each of his seven siblings had a job: cleaning the yard, washing the dishes, making the beds, finding firewood.

His father was a big believer in instilling in his kids to “never let it rest, till your good is better and your better is best,” Harris Jr. recalls.

He also remembers neighbors feeding pigs, then slaughtering them and sharing the meat with their neighbors. They also tended to a community garden and exchanged the vegetables they grew.

“The community actually worked as a unit, rather than individual,” he said.

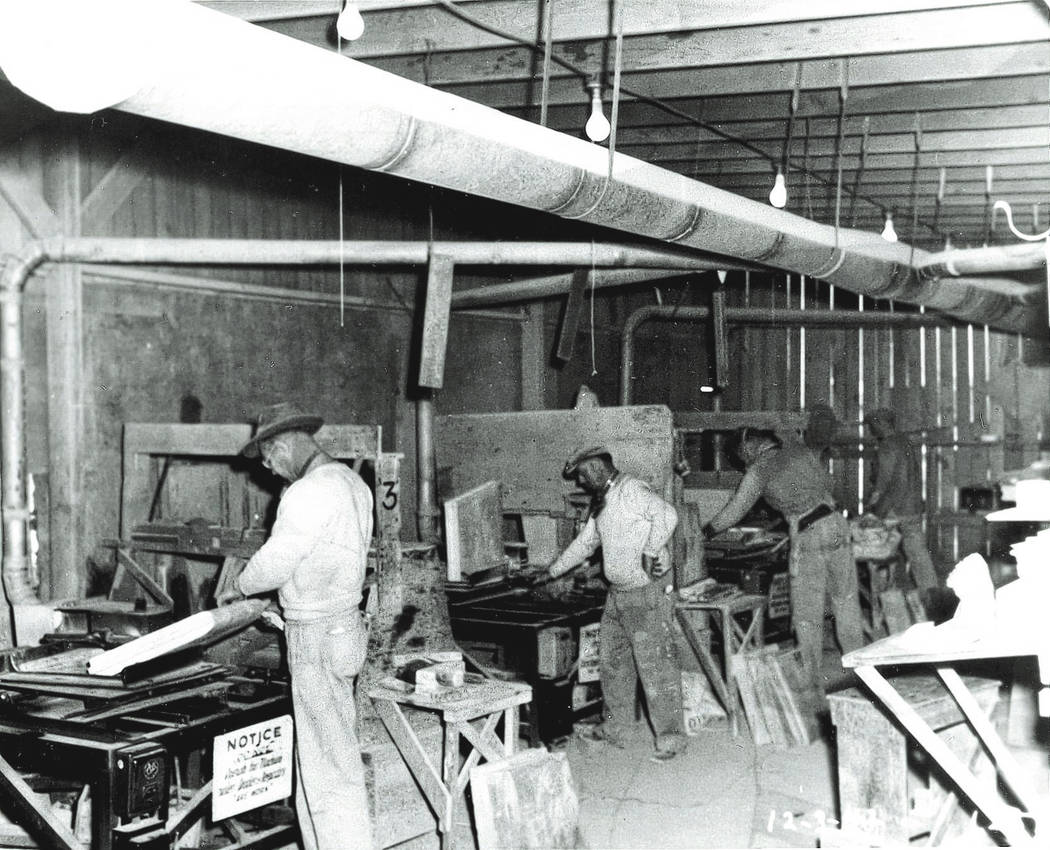

Though the plant brought economic opportunity, it wasn’t immune to racial inequality.

Black workers strike

In 1943, 200 black workers went on strike, backed by black activist James Anderson and Los Angeles-based labor unions.

The men protested the 110-degree working conditions they had to endure, segregated amenities, poor housing and lower pay for the same jobs as white workers.

“Blacks were routinely given the most menial work in the hottest, most filthy areas of the plant,” said White, the UNLV historian. “It was only a matter of time before they reached their boiling point.”

The management gave protesters a deadline to return to work, then terminated those who did not. The only changes that resulted from the strike was the integration of bathrooms and changing facilities, White said.

Despite the workplace tensions, the BMI plant and other neighboring factories that sprung up provided the black workers with economic opportunities that they could only have dreamed of in their Southern birthplaces.

Former state Sen. Joe Neal, an Air Force veteran and Democrat who represented North Las Vegas in Carson City, came from Tallulah, Louisiana, in 1954 and worked at the Titanium Metals plant in the 1960s, starting as a janitor before moving up the ranks.

“We began to make more money, and that attracted more blacks in the area,” he said.

50 cents to $15 a day

He recalls going from 50 cents a day sharecropping on the plantation to working on tractors to $15 a day in Nevada.

“That was a hell of a step up for me,” he said. “In Louisiana, they said, ‘OK you need a job, go to Vegas, report to these people, you got a job. That was the movement that got a lot of blacks out here.”

Some of them did realize their dreams.

Harris Jr. worked as a fireman and in the Navy. In the 1970s, he provided his expertise in fire science for the Nevada Test Site 65 miles northwest of Las Vegas, which also provided many African-Americans with job opportunities in the 1950s, when testing of nuclear devices was a regular occurrence.

In the years since, he and his wife of 50 years, Tisha, have been involved in many economic and community development projects, including the Golden West Shopping Center and the College of Southern Nevada.

They own Unibex Global Corp., which they founded to help advance economic, education and health opportunities for minorities, both globally and in the Las Vegas Valley.

“You got to pay back,” he said. “You’ve got to look for those behind you, to leave something behind better than you left it.”

^

Contact Briana Erickson at berickson@reviewjournal.com or 702-387-5244. Follow @brianarerick on Twitter.