‘They think this was my choice’: Afghan in US works to free family from Taliban rule

Editor’s note: This is the second story in an occasional series.

Every night Benny fights with his wife, their arguments conducted across 7,500 miles, with him in Las Vegas, her in Kabul.

The young Afghan couple was torn apart eight months ago when Benny reluctantly boarded a flight during the chaotic evacuations from Kabul’s international airport, as the U.S. pulled out of Afghanistan and the Taliban regained control. Benny had dreamed of coming to America, but not without his wife and parents.

“She thinks that I left her on purpose,” Benny said about his wife.

The 26-year-old’s first name is Mohammad, but in the U.S. he often goes by the nickname given him as a teenager by American soldiers. He spoke with the Review-Journal on the condition that his last name and details of his background be withheld for his family’s safety.

“They think that was my choice, that was my purpose, to leave them behind,” said Benny, who communicates with his wife from his host family’s Henderson home through video chat, calls and a messaging app.

His wife and parents pepper him with questions about the status of their immigration applications and when the family can reunite in the U.S.

“I cannot provide this information to them because I don’t have the information, either. She keeps just arguing with me because they don’t understand it.”

Taliban threats

His parents and wife now live in an apartment in Kabul, the women never venturing beyond its walls for fear of the Taliban.

In 2017 and 2018, Benny worked for a U.S. government contractor providing IT services to the ministry of interior affairs.

During this period, an assault rifle-wielding gunman shot at him in his car. He received anonymous threats that if he did not stop working for the Americans, his mother, who worked for an international aid organization, would be kidnapped, including details of how it would be done.

He and his mother both left their jobs, and in 2018, he began to work for an Afghan airline. The threats eventually resumed, he said.

As Kabul fell to the Taliban, Benny helped with U.S. evacuation flights out of the city for six straight days, until American soldiers told him and co-workers they were in grave danger and to board a flight themselves.

Today in Afghanistan, “Everyone’s life is in danger, especially those who helped Americans in the last 20 years one way or another, if it was direct or indirect,” said “Ish” Khan, the Washington state ambassador for the nonprofit No One Left Behind. The organization helps former interpreters for American military forces and other Afghans who provided substantial aid to the U.S., in obtaining special immigrant visas, evacuating and resettling in the U.S.

The Taliban has become emboldened, with the world’s attention shifting to Ukraine. A person thought to be a U.S. ally might be tortured or killed, said Khan, whose brother was kidnapped by the Taliban in October and tortured.

“I’m helping many families, including my own, to get them out,” Khan said. “We’re trying to get out whoever we can.”

‘Extreme danger’

Benny’s application for a special immigrant visa includes a letter of support from a U.S. military officer who oversaw his employment as an IT contractor. She wrote that his work with the records of the Afghan national police put him in “extreme danger.”

It also includes a letter of support from a Massachusetts Army National Guard sergeant involved in training the local Afghan police in the village where Benny lived as a teen. According to the letter, in 2010 and 2011 Benny regularly served as a volunteer translator for the Army unit.

Benny’s greatest fear is that the Taliban will connect him, and his work for Americans, to his family.

“It will come out eventually, and when it does, they will be killed,” he said.

The Taliban now sweep Benny’s old neighborhood, looking for weapons and traitors to their cause. They’ve searched his family’s apartment twice since August. To avoid suspicion, Benny’s wife said her husband was working as a laborer in Saudi Arabia.

Seeking safe passage

In reality, Benny is living in Henderson with the parents of the American pilot who flew him out of Afghanistan. He met U.S. Air Force Lt. Christopher Hoffman when the pilot enlisted him to communicate with the 400-plus Afghans aboard his flight.

After Benny arrived in the U.S. and needed a place to stay, he called the pilot, whose parents, Scott and Ellen, welcomed Benny into their home.

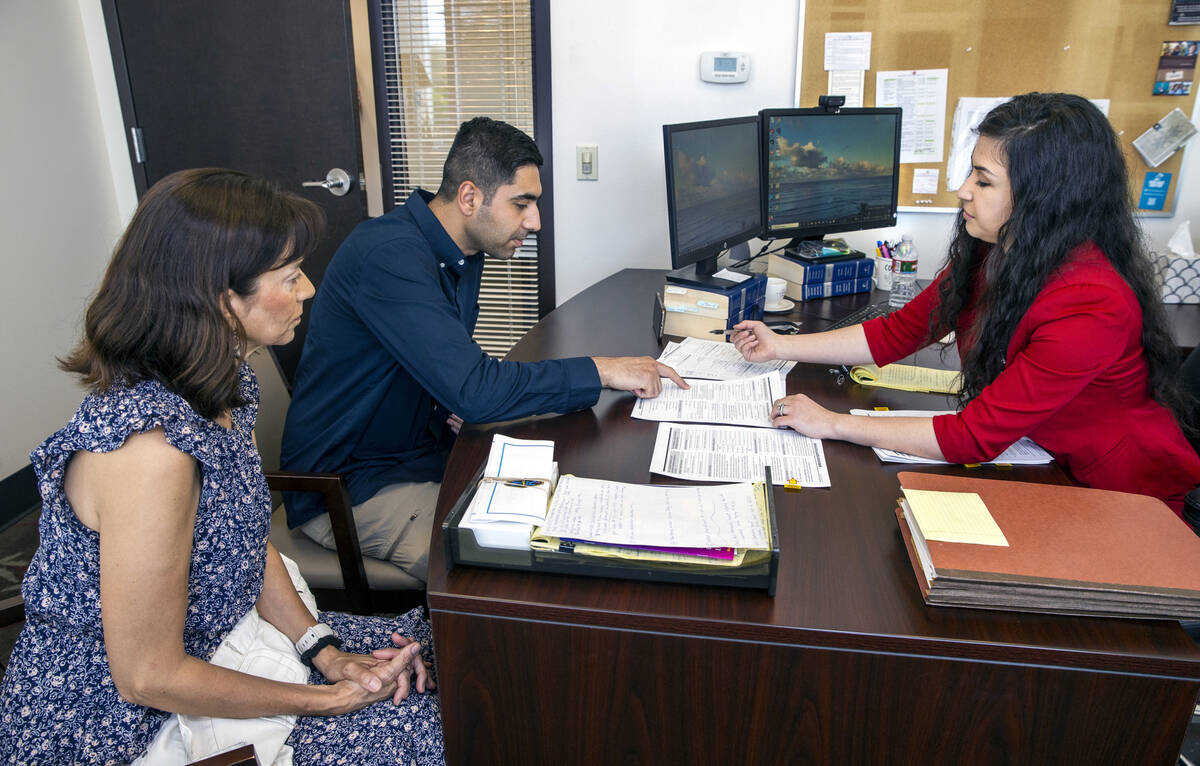

The Hoffmans and an attorney, Ebru Cetin with the Legal Aid Center of Southern Nevada, are helping Benny navigate the maze of immigration. Benny and his wife have been randomly selected through the diversity immigrant visa program, also known as the green card lottery, to be considered for permanent residency in the U.S.

They have until September to complete multiple background checks and interviews. However, his wife can’t complete the process until she leaves Afghanistan, where there is no embassy or consulate.

Benny has applied for humanitarian parole into the U.S. for his parents, another process that cannot be completed from inside their native country.

The family seeks safe passage to neighboring Pakistan, and then to reunite with Benny in the U.S.

For now, Benny sends home money he has earned working an IT job in Las Vegas. He wires the funds to his landlord’s wife, who lives outside of Afghanistan, and his landlord in turn provides money to Benny’s family.

His family recently discovered the visas they had purchased to escape Afghanistan and enter Pakistan were fraudulent. Even if they escape to Pakistan, they will be unable to enter the U.S. without a separate visa from the American government.

“What we need is a piece of paper that says they’ll be welcome,” said Scott Hoffman, a retired Air Force pilot who flies for Southwest Airlines.

A surprise encounter

When he is not working or trying to help his family, Benny said he spends much of his time studying to earn additional IT certificates. Occasionally he has fun, as he did one evening after a surprise encounter at the Nevada DMV.

There, remarkably, he spotted an Afghan man he had met in his native country. They struck up a conversation.

“The night that we drove around the city in Las Vegas. I realized that, yeah, this is one of the cities that I have been dreaming about,” Benny said with a smile. “Yeah, so fancy. A lot of lights. A lot of the nice buildings.”

But he did not tell his wife and parents about meeting a friend.

“I need to have some free time … to be happy. But I cannot tell them the truth. I cannot tell them that,” he said.

“I keep hiding this because they are already feeling hopeless. They want to get out, they want to walk on the street. They want to be free. They want to have fresh air just hitting on their face.”

Benny and the Hoffmans found fresh hope in signs that flights might resume out of Afghanistan.

“I want the U.S. government to look at my family and to think of them as eligible people that can get onto their planes to get out of Afghanistan,” Benny said. “I want them to give some hope to my family, to give some hope to me.”

Ellen Hoffman said, “Hope is our bedrock. We want to keep Lady Liberty alive.”

No way out?

It has been roughly two months since the State Department has chartered flights out of Afghanistan, Khan said.

“Every day it’s getting harder and harder and harder for us to get people out,” said Khan, who has been in the U.S. for eight years and previously worked as an interpreter for a U.S. special forces officer, even fighting alongside him.

“The State Department was running some flights, but they’ve been having problems with the Taliban,” which increasingly is restricting Afghans from leaving the country, he said.

The State Department gives priority to Afghans such as interpreters, commandos and intelligence agents trained by Americans who have special immigrant visas, Khan said. Priority also is given to those in the final stages of securing such a visa.

Commercial flights are highly restricted. “Right now, the Taliban isn’t letting anyone out without a legitimate reason,” such as a doctor’s visit, he said. “If it’s a woman without a husband, then she cannot even get on a plane.”

“I’m helping many families, including my own, to get them out,” Khan said. “We’re trying to get out whoever we can.”

Khan wants to see the U.S. work with countries such as Qatar and Pakistan to apply pressure on the Taliban to let U.S. allies depart.

“They need to keep their promises,” he said of the U.S. government. “They need to stand with those who stood with them for the last 20 years.” He estimated there are 50,000 to 60,000 high-risk Afghans still in Afghanistan who applied for special immigrant visas.

The State Department’s current focus is on supporting the departures of U.S. citizens, lawful permanent residents and their family members, a spokesman said. It is also facilitating the departure of “our Afghan allies” and their eligible family members.

The State Department is “committed to reuniting families who may have been separated during relocation operations in August 2021,” the spokesman said.

“We will not be sharing details of these efforts due to safety and operational considerations.”

Running out of time

To help Benny and his family, the Hoffmans have enlisted the support of the offices of Nevada Sens. Catherine Cortez Masto and Jacky Rosen.

Members of both offices have met with them but have been unable to identify a clear path forward, the Hoffmans said.

In an email to Benny and the Hoffmans, Rosen’s office said that it contacted the State Department, Bureau of Consular Affairs, to inquire about Benny’s special immigrant visa application.

An assessment by the bureau’s Congressional Affairs Unit included in the email said that his application, filed in late November, “puts him behind probably 90 percent of the applicants undergoing processing.”

The assessment also said that his application could be rejected outright because he mistakenly left one question blank.

“We understand that this is not the response you were hoping for but we hope that it still (is) helpful and informative to you and your attorney,” the email from Rosen’s office said.

The senators’ offices said they could not comment on specific casework because of privacy and safety concerns. A backlogged U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services is processing thousands of background checks for humanitarian visas, including those Cortez Masto has flagged for expedited review, her office said.

The offices of both senators say they will continue to offer their help, but Benny and the Hoffmans fear they are running out of time.

“We are a family who puts the flag out each day, a four-generation veteran family and one that loves this country,” Scott Hoffman said. “However, this situation and the incompetence and lack of progress for at-risk allies has been hard to take.”

Cetin expressed confidence that through the diversity visa program, Benny’s application for permanent residency, a path to citizenship, would be approved and that in the interim he will be allowed to live and work in the U.S.

“The problem that really gets into your gut is the spouse,” whose current chance for a visa expires in September, Cetin said.

This is one of many things that Benny can’t bring himself to tell his wife.

“I cannot tell (her) that nobody in the United States government cares about Afghanistan and Afghans anymore,” he said. “I cannot give them a negative image of the country which I have dreamt about for many years.”

Contact Mary Hynes at mhynes@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0336. Follow @MaryHynes1 on Twitter.