Las Vegas’ dry desert reduces disease problems in plants

There are many reasons why living in a desert low in humidity is a good thing. One is fewer disease problems. Desert climates are notoriously low in humidity, particularly as the day gets warmer, so we enjoy fewer plant diseases and worry about them less than in places like Seattle or Tampa, Florida. But plants growing in the desert do get plant diseases.

Plant diseases are classified into two types: those caused by living agents such as bacteria, fungi and viruses (biotic) and those caused by nonliving agents (abiotic).

Cures for biotic diseases, if identified correctly, can be found by Googling or watching YouTube videos. Curing these biotic diseases can be addressed nationally or internationally. But abiotic plant diseases, those encouraged by living in our desert climate — strong sunlight, poor soil drainage, plant selection — are desert conditions and give people moving here the most problems.

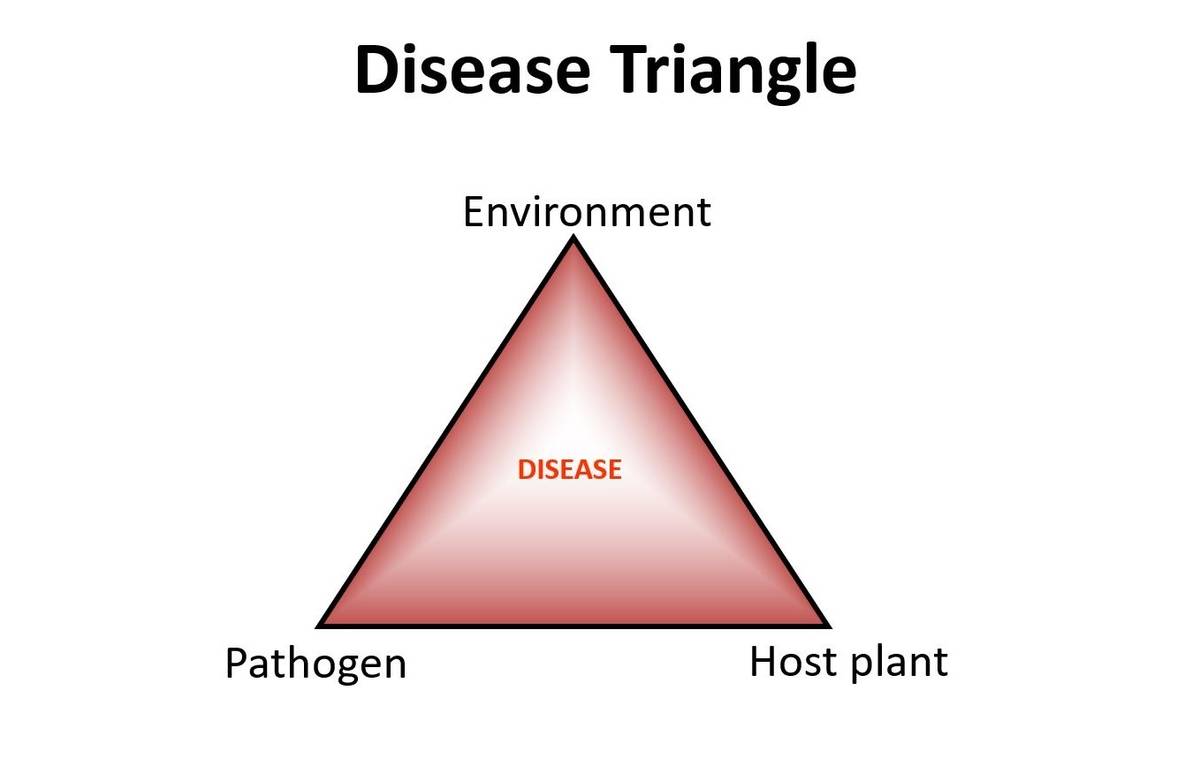

The disease triangle is a powerful concept for controlling plant diseases of all types. It assumes three things are necessary for diseases of all types to start: the presence of a disease agent, susceptibility of particular plants to disease and the right environment.

Remove any of the three parts of the disease triangle, and the disease stops.

Preventing diseases from starting costs time and energy to implement. Sanitizing mowers and hand tools helps remove biotic disease agents. So does keeping weeds and insects under control.

Selecting varieties or types of plants better equipped for handling the heat, cold or low humidity addresses the second side of the triangle. Choosing where to put a raised bed or planting a type of tree or shrub best suited for a particular home microclimate addresses the third. Not doing these things costs money instead of time and energy spent on prevention.

Still, biotic diseases do occur. Fireblight and Coryneum blight are two biotic diseases minimized by selecting the right type or variety of fruit tree. Summer blight of tall fescue lawns is minimized by cleaning mowers and managing the lawn differently.

Before buying a chemical for controlling diseases after it starts, try the triangle approach for disease prevention.

Q: My tomato plants are growing OK, but I wonder if the leaves could be telling me if I’m missing something. Some leaves are very flat and what I’d consider to be normal. Other leaves are curled on the edges. I initially thought aphids, but they don’t appear to be on the leaves.

A: What is normal? Knowing what normal looks like comes from seeing a lot of different types of tomatoes, either from years of gardening experience or looking at lots of tomato leaves.

You didn’t tell me the variety of tomato that you’re looking at or if you are looking among different varieties. Some varieties of tomato have relatively flat leaves, and other varieties have curling leaves.

Curling leaves can resemble aphid infestations. Experienced gardeners know the difference between bumpy but flat San Marzano leaf varieties and the curling Early Girl variety of leaves. Sometimes curling leaves can be from the heat. This is where experience in gardening becomes important.

If my tomato plants appear healthy and producing fruit like they should this time of year, I don’t worry about whether they are curling or not. I start to get concerned when they are off-color (brown), damaged or are not producing as they should. It’s a lot of detective work.

I don’t like to see very dark green leaves in plants preparing to flower. Dark green leaf color when they are trying to flower can mean access to very rich soils or overapplication of nitrogen fertilizer.

When plants are very young, dark green is OK. But when you want them to produce fruit later, plants fed too much nitrogen — dark green leaves — can delay flowering.

In some varieties, this results in “all vine and no fruit.” Tomatoes should be hungry when starting to fruit. Once they start to produce, then go ahead and feed them.

Q: Last fall I purchased a 50-pound bag of large alfalfa pellets for $11. My first idea was to use it as the nitrogen source in my compost pile. Another option is to add it to my raised beds as it is and let it decompose. The third idea was to make alfalfa meal tea by letting it sit in a larger bucket of water and ferment for several days to a week and then watering with it. What is best?

A: I have never worked with alfalfa pellets, so I don’t have any experience except using it as a feed for animals. Most compost is high in phosphorus if it comes from animals and high in microorganism counts. I personally think it is wasted as a compost amendment because there are plenty of kitchen scraps available high in nitrogen for composting.

One thing I like about alfalfa pellets is their high potassium value. Potassium is hard to get in an organic form.

I like that they use molasses as a binder for the pellets, which probably helps for feeding as well. Molasses is part of the Korean natural farming method used in Asia. The University of Hawaii talks about it as a technique used for boosting soil microorganism counts. In my opinion, the primary benefit of natural farming is the stimulation of microbial activity.

I like your ideas about using it as a soil application. I would look closely at the Korean natural farming techniques for reducing the need for fertilizers and discussed by the University of Hawaii.

Alfalfa pellets will keep a long time dry, so I would use them to occasionally boost production when needed. I like it just as a soil amendment with supplementing it with molasses. I don’t think natural farming has been tried or popularized in desert soils as much as popularized in Asia.

Q: Have you had any experience in using potassium bicarbonate in a solution as both a treatment for and preventative control of powdery mildew?

A: I do not have any experience with potassium bicarbonate for controlling powdery mildew. I suggest using the disease triangle and prevent this disease by adding more sunlight, reducing water splashing on the leaves and increasing dry air movement and leaf drying through pruning and leaf removal (changing the environment).

Different powdery mildew diseases are specific to each plant, but collectively this disease needs low humidity compared with many other fungal diseases. Powdery mildew disease of grapes is prevented mostly through leaf removal and improving air circulation. Occasionally fungicides are needed when outbreaks are triggered by spring rain.

Q: I have a 3-year-old pomegranate shrub with stems that are dying back now that the weather has become hot. What do you recommend doing?

A: A common disease of fruit trees in wetter climates is root or collar rot caused by a fungal soil disease organism that likes wet soil called Phytophthora. This disease can be a problem in pomegranate if the soil is kept wet, if mulch on top of the soil is touching the stems of young plants and if there is poor water drainage. It is most common in avocado trees and other fruit trees when they are young.

The soil must be given a chance to dry on the surface, and anything wet touching the stems is raked back. Dry soils contain this disease, but as soon as the soils become wet, then this disease organism begins to flourish.

It attacks the parts of the shrub entering the soil choking the tops and causing them to die. It is a bigger problem when temperatures are warm or hot because this is when the disease organism flourishes and when plants need the most water.

Prevention of this disease is much easier and less costly than applying fungicides to control it. But fungicides such as copper compounds may be needed to stop it from getting worse.

Let the soil dry out and keep an eye on it for moisture, particularly the surface. Clear the area around these stems of weeds and any mulch that touches the stems.

Applications of fungicides that control Phytophthora collar rot may be recommended until irrigation and soil moisture is under control, the disease stops and the soil is dry again. If the disease is not stopped, it can spread to the roots and cause the entire plant to die.

Bob Morris is a horticulture expert and professor emeritus of the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. Visit his blog at xtremehorticulture.blogspot.com. Send questions to Extremehort@aol.com.