Clark County deaths in 2017 hit highest mark since 2001

More people died in Clark County in 2017 than during any other year since at least 2001.

Last year, 17,817 people died in the county — about 800 more than in the year before. Not all deaths go through the Clark County coroner’s small central valley office, but nearly 75 percent of deaths were reported to the department in 2017.

The Las Vegas Review-Journal examined 4,005 cases the office investigated in some capacity. Deaths without a determined identification or cause, as well as those not examined by the coroner, were excluded from the data.

The 58 victims of the massacre on Oct. 1 and the shooter, who died of a self-inflicted gunshot wound, were not included in the data provided to the Review-Journal.

Clark County Coroner John Fudenberg would not answer questions about the data.

Roughly half of the deaths investigated by the coroner’s office were natural, the data show.

Homicides ravaged the county in record numbers last year, but they accounted for only about 5 percent of deaths investigated.

About 38 percent of the more than 200 people whose deaths were ruled homicides were black, the data showed, and more than 7 out of 10 homicides were the result of gun violence.

One of the victims, 35-year-old Christian Jewell Bracko, was gunned down at an apartment complex Dec. 20.

“It was devastating,” said Bracko’s mother, Stephany Morris, who was with her son just before the shooting.

Morris said she drove around all night in fear when she learned of his death. Police have not arrested anyone in the shooting.

“I moved to California,” she said. “I couldn’t stay there no more.”

Bracko had married three weeks before the shooting, Morris said.

The coroner’s office saw more than twice as many suicides as homicides last year. In 2017, the coroner’s office handled 476 suicide cases, up slightly from the year before. About half of suicides last year were the result of a gunshot.

White men were the most affected by suicide, with more than 250 cases last year. Eight of the 11 people under 18 who killed themselves did so with a gun.

Heat deaths

The desert heat killed scores of people last year.

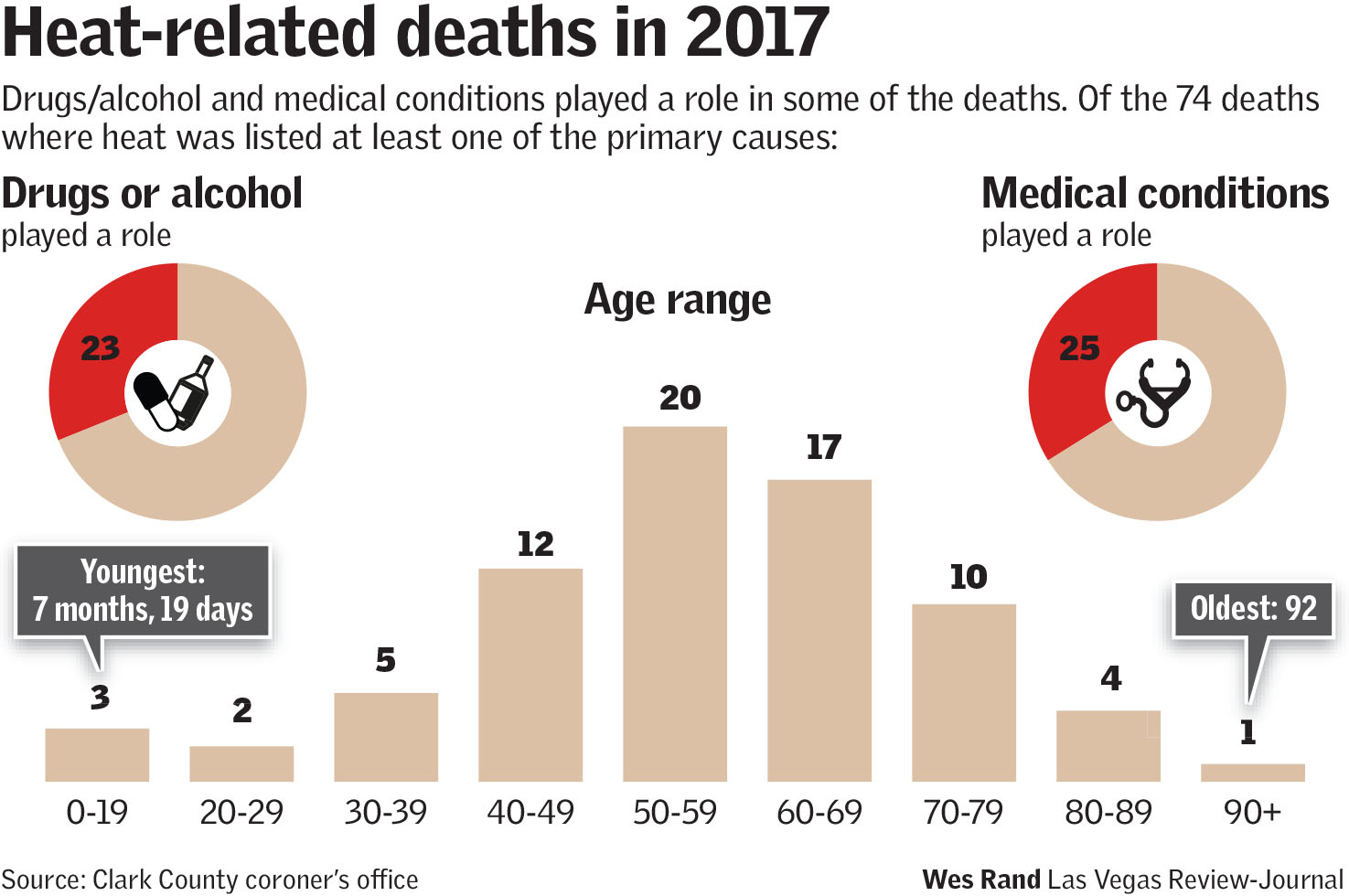

Between May and October, heat was a primary cause of death for 74 people, and it was listed as a significant factor in 90 more deaths.

Kathryn Barker, an epidemiologist for the Southern Nevada Health District, said overweight people and those who have underlying chronic conditions are at a higher risk of dying in the heat.

Young children and older people tend to be more susceptible to dying in extreme heat, Barker said. The youngest victim was 7 months old, and more than 40 percent of heat-related deaths involved people 60 or older.

Many heat-related deaths in 2017 were coupled with medical conditions, and others were associated with drug or alcohol use.

Accidental drug and alcohol deaths

Opioid misuse and addiction continues to plague the country, but Clark County saw a slight decrease in its number of opioid-related deaths last year. In 2016, more than half of the roughly 550 accidental drug deaths in the county involved opioid use.

Drug and alcohol use contributed to about 450 accidental deaths last year. About 210 cases had at least one opioid listed as a primary cause of death.

Opioid-related deaths are trending downward in Clark County but continue to climb nationally, Barker said. She analyzes death certificate data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Data from the coroner’s office tend to be more comprehensive than data provided by CDC, she said.

The number of opioid-related deaths in Clark County has steadily declined since 2011, Barker said. In 2016, the rate of fatal opioid overdoses in the county dropped below the national rate for the first time since the Health District started tracking the statistic, Barker said.

“We peaked earlier on and we were able to identify the issue a little bit earlier,” Barker said.

Officials made changes to prescribing practices, such as implementing a prescription drug monitoring program at the state level after the peak, Barker said. Doctors also have encouraged using alternatives to opioids for pain management.

Nevada also has seen increased funding and resources to fight the opioid crisis, she said, as well as increased access to Naloxone, a drug that reverses the effects of overdoses.

“There’s no one silver bullet, obviously, but a lot of things have been happening to kind of change the landscape,” Barker said.

Contact Blake Apgar at bapgar@reviewjournal.com or 702-387-5298. Follow @blakeapgar on Twitter. Contact Mike Shoro at mshoro@reviewjournal.com or 702-387-5290. Follow @mike_shoro on Twitter.