Coroner continues search for real names of John and Jane Does

No one knows whose bones they are.

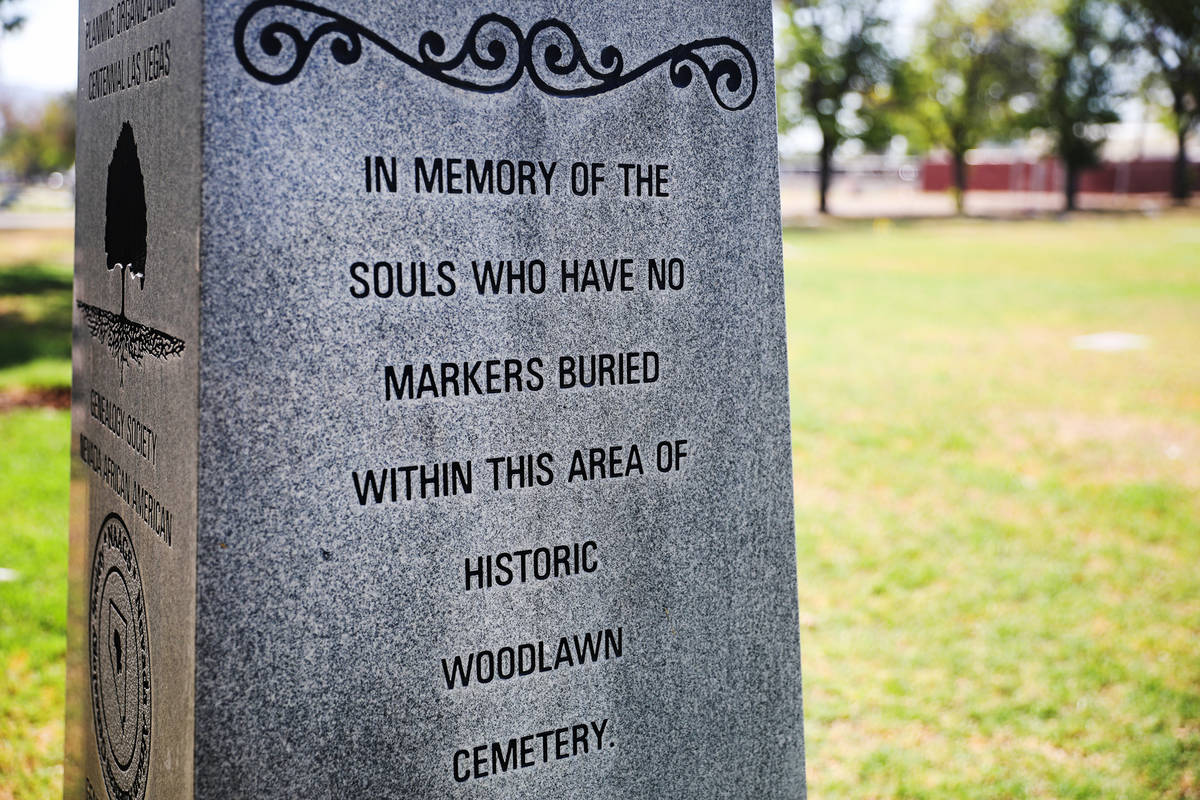

There are no headstones. Some lie underneath patches of desert gravel, long abandoned by a broken sprinkler system failing to keep the grass alive. A stone obelisk erected in 2018 tells visitors at Woodlawn Cemetery that although they left behind no names, the unidentified were loved by someone, somewhere.

The Clark County coroner’s office investigates hundreds of deaths annually, but 273 bodies remain unidentified, county spokesman Dan Kulin said. Many of them have been moved to a cemetery or cremated and placed in a county crypt.

“It is really sad, and it breaks my heart that people will die and have no ID, so their family has no closure to know where they are,” said Betty Wiley, a cemetery administrator at Woodlawn Cemetery in downtown Las Vegas.

Many of the cases date back decades — only eight of the unidentified bodies are from 2021, Kulin said. Seven are children less than a year old.

Some are adults who were likely homeless but died without ID cards or leads pointing to immediate family members. They are homicide victims and potential drowning victims. Some were found as skeletal remains. The only common thread is the label: John or Jane Doe.

Clark County Coroner Melanie Rouse, who took over the job in early June, said getting information to families in search of closure is one of the most important roles for the coroner’s office.

“That’s huge for us, is trying to get those families back with their loved one and give them the answers that they may have been looking for, for a very long time,” she said.

Sometimes, a ‘waiting game’

Once a death is reported to the coroner’s office — often when an investigator is called to a crime scene or car crash — officials immediately begin gathering information, Rouse said. Witnesses and ID cards make the process straightforward, but Rouse said the investigation is complicated when someone’s body is decomposed or there are no definitive leads.

In late May, law enforcement and coroner’s office investigators were faced with a case without leads when the body of a 7-year-old was found near a remote trailhead in Mountain Springs. The boy had no clothes,“multiple injuries” on his body, and had been strangled, although information about what may have killed him was not publicly released at the time.

Hours after the boy’s body was found, investigators thought they were on the right track when a woman told officials that a police sketch resembled her son. The woman was interviewed by police and coroner’s office investigators, and after reviewing pictures of the boy’s body, she signed an affidavit saying he was her son, police have said.

But the woman’s son was instead found alive and safe with his father and half-brother in central Utah. They had been camping without cell service.

Kulin said identifications are made through pictures “fairly regularly” but are considered preliminary until the coroner’s office completes its investigation. Police have said the initial identification in the Mountain Springs case was made public because officials were concerned about the boy’s half-brother.

A tip out of San Jose, California, led to a breakthrough in the case, and the dead boy was identified as 7-year-old Liam Husted. Cases such as Liam’s, where investigators have no direct leads, are the hardest to solve, Rouse said.

“Those are the circumstances where you do your best, you submit the information you have, whether that is fingerprints, whether it is entering the information into the national databases and not getting hits back,” Rouse said. “And sometimes it is just a waiting game until somebody comes forward and declares that that person is missing.”

Jane “Silver State” Doe

On Sept. 19, 1995, a woman’s severed midsection was found on a conveyor belt at the Silver State Recycling plant, at 333 W. Gowan Road. Detectives combed through piles of trash to find the woman’s dismembered head, arms and legs, but not all of her body could be found.

“We’ll probably never have a definitive cause of death unless we find all the body parts,” Metropolitan Police Department homicide Sgt. Ken Hefner told the Las Vegas Review-Journal at the time.

Jane “Silver State” Doe, who was in her early 20s, may now have been an unnamed homicide victim for longer than she was alive. Police know basic details — she was 5 feet tall with brown eyes, brown hair and auburn highlights — but nothing else.

But like the coroner’s office, Las Vegas police don’t stop investigating unidentified bodies. Metro homicide Lt. Ray Spencer said cold case detectives are actively investigating the Jane “Silver State” Doe case and are conducting genealogy testing in hopes of identifying her.

“We are hopeful to have preliminary results within the next couple of months,” Spencer said.

Meanwhile, the information on Jane “Silver State” Doe and other unidentified bodies has been entered into databases such as the National Missing and Unidentified Persons System.

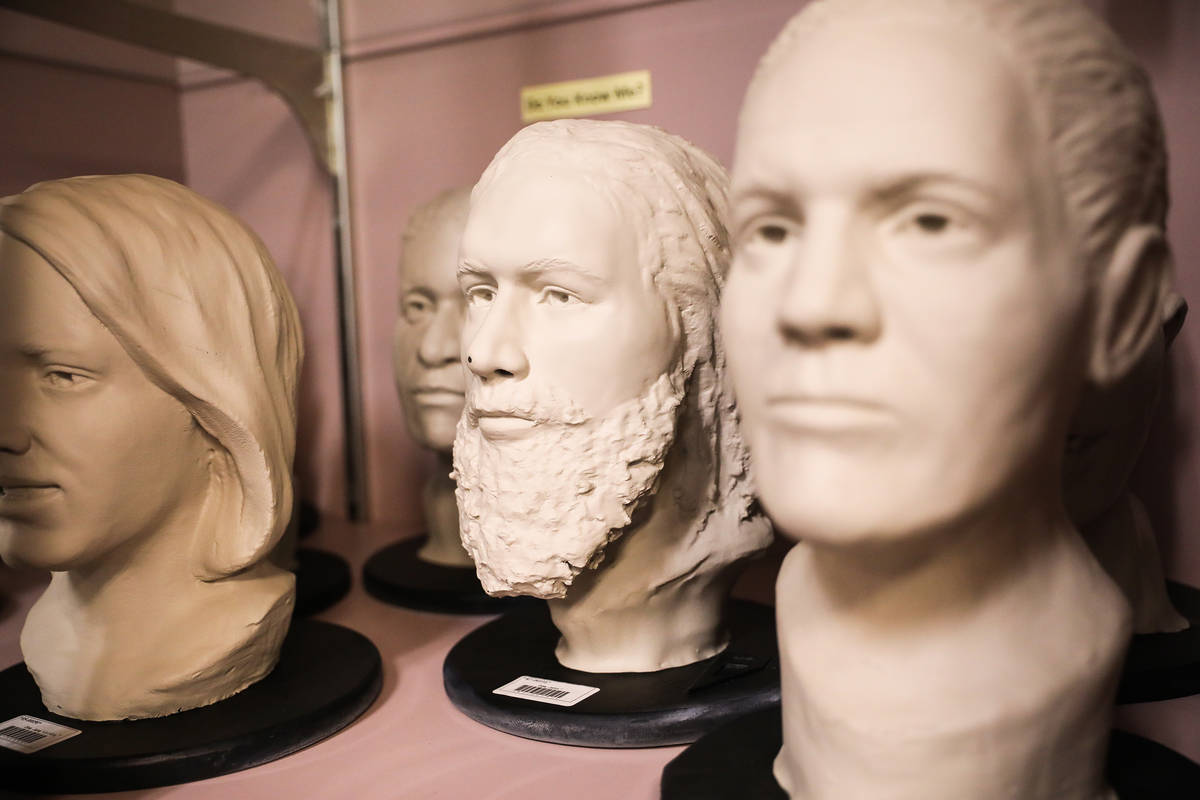

While investigators hope that sketches can lead to an identification, other database entries have images of white busts meant to depict what the unidentified person may have looked like while alive.

About a half-dozen of the busts are on display in the Clark County coroner’s office, tucked away in a glass case. Without names, the busts only have a number to differentiate them.

More details can be found in the bits and pieces of information uploaded to the database. The man whose decomposing body was found in 1987 had a full beard with a “distinct reddish tint.” ATV riders who found a woman’s skeletal remains in 1991 also found bell-bottom jeans. The man found in Lake Mead in 2003 was wearing green shorts with a black belt.

The database doesn’t indicate where the unidentified remains are buried. Without the memorial marker or records at Woodlawn, it would be impossible to know that hundreds of unidentified people have been laid to rest there.

“It is hoped that in the future, with modern technology and DNA advancements these unknown souls can be exhumed and identified,” the obelisk at Woodlawn Cemetery reads. “Over 40,000 unknown person are listed in national data bases. Let us always remember!”

Contact Katelyn Newberg at knewberg@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0240. Follow @k_newberg on Twitter.