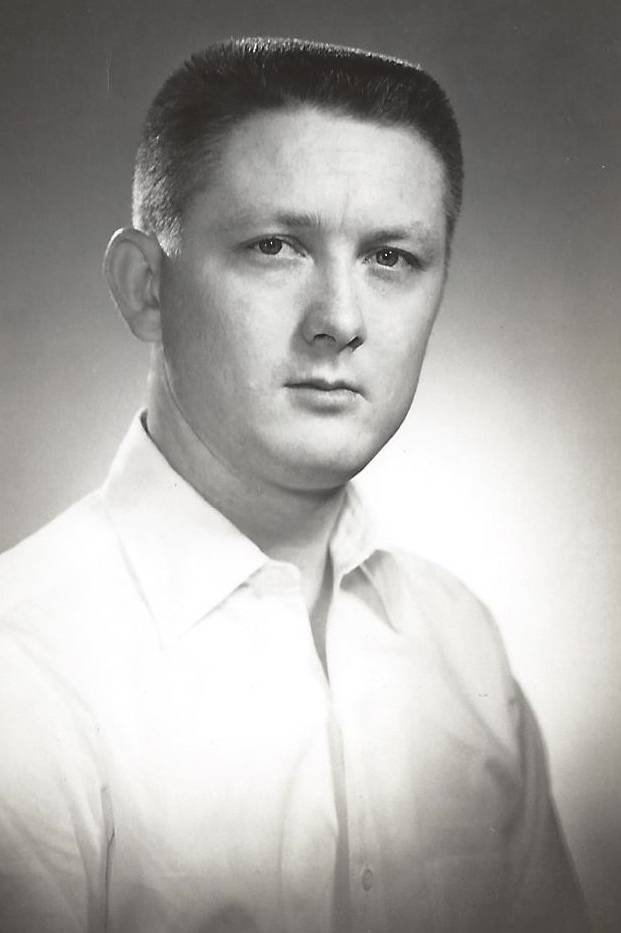

John Robinson spent decades fighting for justice. He couldn’t beat COVID-19.

John H. Robinson spent decades fighting for justice on three continents.

After serving as a naval aviator during the Korean War, he went to work for the U.S. Department of State advising law enforcement agencies during extreme political instability in Vietnam and Nicaragua.

He then took his law enforcement career stateside, working in California before moving to Las Vegas in 1975, where he worked first as a federal probation and parole officer before being appointed the state’s U.S. marshal by President George H. W. Bush in 1990.

Robinson knew war. He also battled the mob and lesser criminals for more than 20 years. But it was complications due to a microscopic virus, COVID-19, that ended his life at Las Vegas hospice facility on July 6 — just two days short of his 91st birthday.

“He used to say the ‘H’ in his middle name stood for honor,” said his widow, Susan. “Most people didn’t realize until long into knowing him it was Herman. But honor more than anything epitomizes what he was. He was the most honorable man I ever knew.”

Susan and John celebrated their 50th marriage anniversary in March. She said her late husband lived his life with clear principles: Honesty, dignity and integrity.

“He didn’t get along with everyone, and a lot of times, it was because they didn’t share those ideals,” Susan Robinson said.

‘A life well lived’

The couple raised three daughters, Krista, Brittany and Carey, from John’s previous marriage. Each married men whom John adored, his wife said, as they shared much of his value set. He had three grandchildren and a fourth on the way.

“His timing was impeccable, as he hated birthdays and insisted that he had stopped having them years ago,” Krista Robinson Hadavi said in a Facebook post. “My dad lived a long, wonderful life full of love and adventure. Truly a life well lived.”

Hadavi included a photo of her and Robinson dancing at her wedding.

“My dad loved to tell stories and I can see he is telling one to me here,” she said. “I can also tell by the look on my face that it might not have been entirely appropriate for the situation.”

His eldest daughter, Carey Parra, said her father was a character. He once tried to mail her young son a souvenir from the Las Vegas desert — a scorpion — but the insect was crushed into dust by the time it arrived at her home in California.

“I wasn’t thrilled with that gift,” she said.

Robinson grew up in Oklahoma.

Like so many others living through the Great Depression, his parents loaded up their old Ford and headed for California. They camped along the highway until reaching the Golden State. The family picked fruit in the fertile Central Valley before ultimately settling in Sanger.

“He told that story often. It was like a chapter out of ‘The Grapes of Wrath,’” Susan Robinson remembered.

Robinson attended Sanger High, where he set a record in the hurdles. He joined the U.S. Navy on his 19th birthday, July 8, 1948, and served as a navigator until 1952.

He then attended Fresno State University, where he studied criminology. He befriended another student, Gene Sadoian, whom he later worked with in the federal probation and parole department for Southern Nevada. Through Sadoian, he met a young basketball player who would follow a similar journey from Fresno State to Las Vegas: Jerry Tarkanian.

Susan Robinson met her husband during his first law enforcement job at the California Department of Alcohol and Beverage Control, where he worked undercover throughout the 1960s. The two were married in 1970.

Posts in Vietnam, Nicaragua

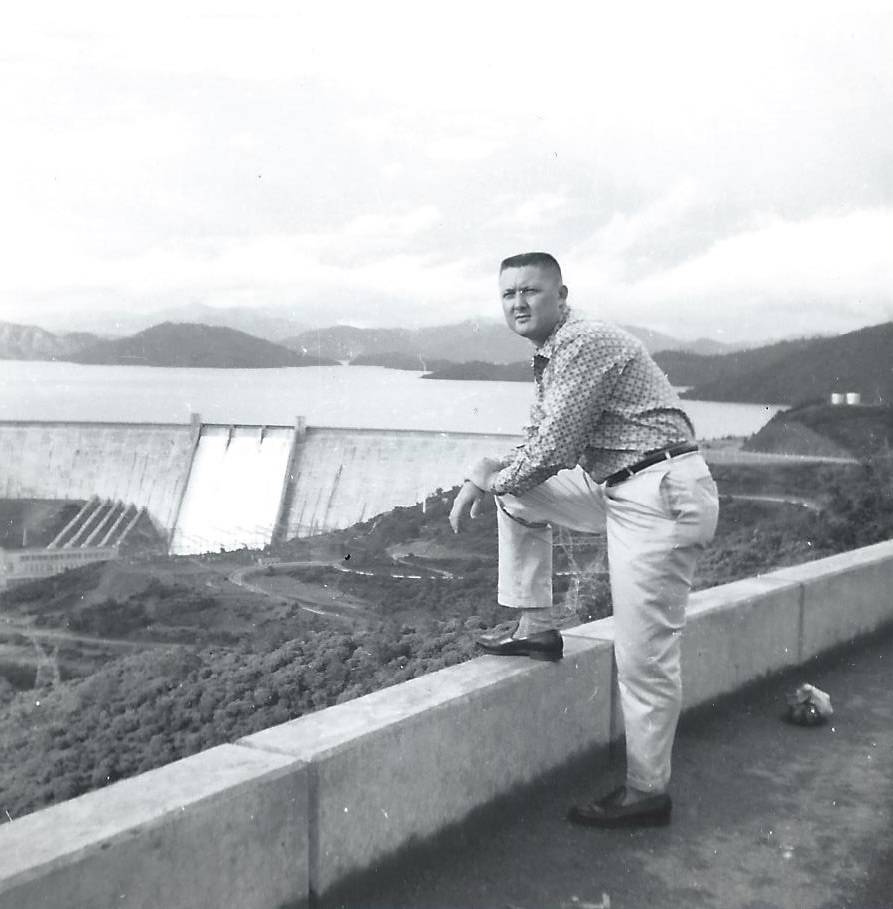

Robinson eventually moved to the State Department. Susan Robinson was also able to secure a federal job that allowed her to travel with her husband to Vietnam, where he advised local law enforcement.

At least officially.

“I don’t know how much of this I can tell you, but he worked for the Agency for International Development,” she said. “He was a police adviser. That was his cover, at least.”

After the peace agreement in 1973, the couple moved to Nicaragua, which was rebuilding after a horrific earthquake. Robinson served as a consultant on the rebuilding of the nation’s police force.

The couple settled in Las Vegas in 1975.

Susan Robinson said her husband didn’t speak often about his work in federal law enforcement, but he regularly interacted with members of organized crime.

“He enjoyed working with the mob,” she said. “They were gentleman. They had a code of ethics. It was very different from his or society’s, but it made them predictable. They agreed to disagree. There was a sort of mutual respect there.”

Nevertheless, her husband hated the idea of the Mob Museum and never visited it, saying it glorified the horrible crimes committed in this area.

When he retired in 1993, his youngest daughter was only 9. With Susan Robinson still working, her husband took on a role as primary caregiver, chauffeur and cheerleader. He once received an award for never having missed a volleyball game or practice.

Even though his work was demanding, he always found time for his family, Hadavi said of her father. He even coached her soccer team for a time, despite not knowing much about the game.

Hadavi said he raised three girls to be strong, independent women who felt valued, loved and a sense of self-worth.

Hospitalization

Robinson entered the hospital on June 2 with a variety of symptoms, his wife said. He tested negative for COVID-19 and seemed to be improving after being moved to a rehabilitation center.

Then his condition took a turn for the worse, and a second COVID-19 test came up positive.

“People ask me if I’m angry, since it appears he got it in the hospital,” Robinson said. “No. These things happen. We took him to four different hospitals, and everyone was taking precautions. I got my temperature taken and screening questions everywhere we went. They did the best they could.”

Robinson said she and her husband had stopped leaving their home, save for doctors appointments, since the pandemic broke out. She cautioned others to do the same.

“Take precautions, lower your odds, but also don’t take anything for granted,” she said. “I do get a little upset when people say this is no big deal. My husband died because of it.”

Robinson was able to see her husband on Sunday, and her youngest daughter said goodbye just hours before his passing on Monday. He will be cremated, she said, but any memorial will have to wait until after the pandemic.

“He didn’t open his eyes, but I think he knew we were there,” Susan Robinson said of that last visit. “He moved when I said who I was and talked about the girls. He lived a full life. An exciting life… his family loved him, and he loved them.”

The Review-Journal wants to tell the stories of those who have died due to the coronavirus. Help us by submitting names of friends or family, or email us at covidstories@reviewjournal.com.

Contact Rory Appleton at rappleton@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0276. Follow @RoryDoesPhonics on Twitter.