Kids’ hospice offers hope-of-life care in Las Vegas Valley homes

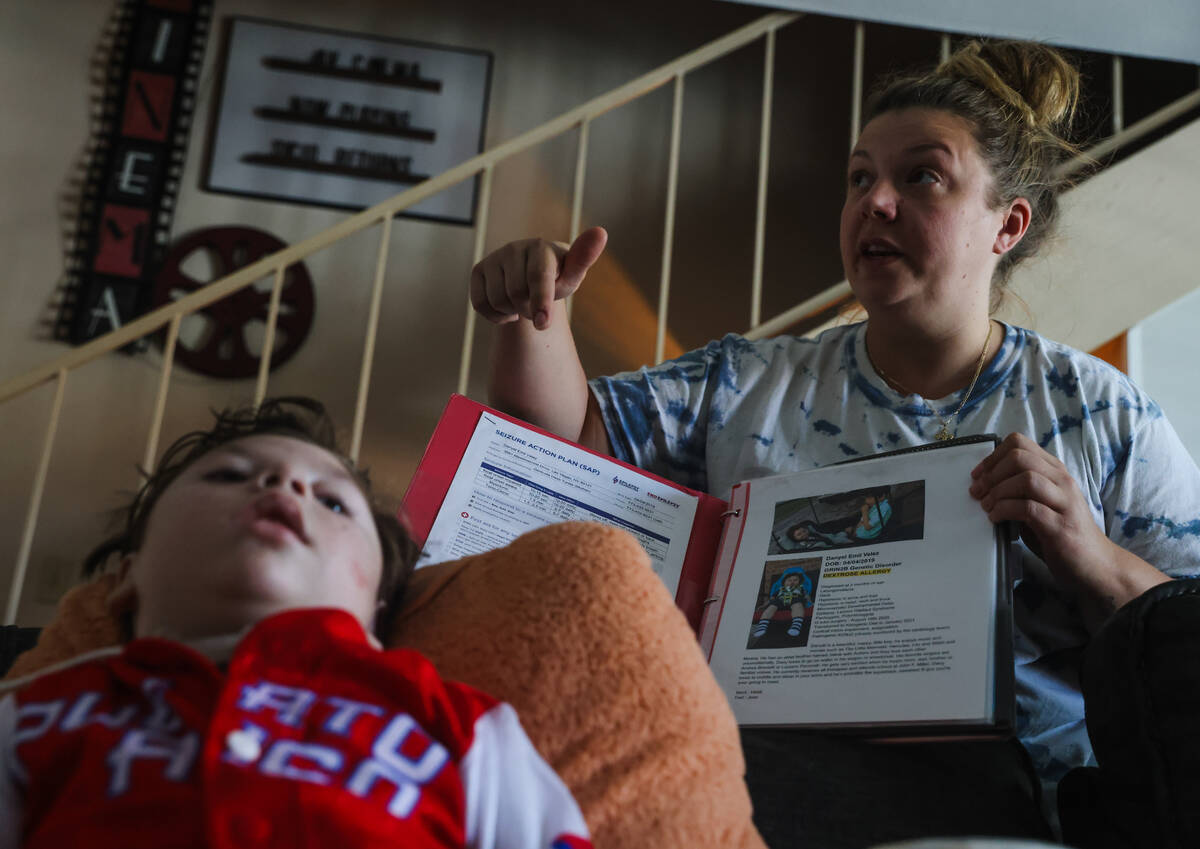

Heidi Tunea carried her 5-year-old son, Danyel Velez, down the stairs to the living room of her eastern Las Vegas home and placed him on a couch.

The boy stared forward, lying on his back, his body shaking from an epileptic seizure related to a rare genetic disorder known as GRIN-2B. It brings intellectual disabilities, cerebral palsy and other neurological problems that make it hard to digest food, so he has to be fed through a tube leading to his intestines.

Tunea recalled a scary moment for the family when he suffered from liver failure and a form of pneumonia.

“We almost lost him in 2020,” she said. “Luckily, he’s my little hero. He came out of it.”

“But that’s gradually what this disease does,” said Tunea, who was next to an IV stand holding a bag of the white liquid that provides nourishment for Danyel. “So it’s like the seizures, the gastrointestinal, the heart, everything. So it kind of just sets off this whole, like, ripple effect.”

Danyel, who cannot walk or talk, is one of the complex health cases handled by 1Care Hospice, a hospice for children that oversees at-home care for about 190 kids in the Las Vegas Valley when staying in a hospital room is not feasible, much less affordable. His brother, 8-year-old Jakob Velez, also is in the 1Care program.

Comprehensive comfort care

Known for palliative care for kids and young adults ending at age 21, the program is called a “hospice” in the newer sense of the word, said Courtney Kaplan, director of community affairs for 1Care. The program is 100 percent covered by government-funded Medicaid.

The U.S. government’s National Institute on Aging states on its website that “hospice provides comprehensive comfort care as well as support for the family, but, in hospice, attempts to cure the person’s illness are stopped.”

“Hospice is provided for a person with a terminal illness whose doctor believes he or she has six months or less to live if the illness runs its natural course,” the institute states.

But in 1Care’s juvenile hospice, palliative care is provided for children with severe conditions but who don’t necessarily have terminal illnesses and can receive treatment while living with their parents and siblings, Kaplan said.

The Mayo Clinic in Rochester, N.Y., defines palliative care as “a specialized medical care that focuses on providing relief from pain and other symptoms of a serious illness” and “does not depend on whether your condition can be cured,” according to its website.

This modern approach to hospice got its start in 2010, with a provision in the federal Affordable Care Act giving children with challenging physical and mental conditions the ability to receive government-paid medical and behavioral assistance — and psychological and spiritual counseling for their family members — in the home, according to Kaplan.

“When it comes to hospice, typically you have to choose if you want aggressive treatment, be it chemotherapy, radiation, any of those kind of more aggressive life-sustaining treatments,” Kaplan said. “If you want to keep doing that, you can’t apply for hospice.”

However, the Affordable Care Act grants an exception for children, permitting them to receive those aggressive, curative — and expensive — treatments and potent medications while in a medically fragile state in a hospice setting, Kaplan said.

1Care also accepts payments via employer and private medical insurance, though most of the kids’ medical expenses are covered by Nevada’s Medicaid based on family or patient income or the state’s Katie Beckett Eligibility Option, which covers the expenses of kids under 19 based on their complicated medical needs and not income, she said.

Aside from 1Care, two other firms in the valley offer similar services, Covenant and ProCare, according to Rabea Alhosh, a pediatric doctor and assistant professor for pediatrics at the Kirk Kerkorian School of Medicine.

“The majority of our patients are not terminal,” said Alhosh, who works with Covenant. “The difference between palliative care and hospice is palliative is helping support them through illnesses that may not lead to early death. Some of these kids can live for years, some are graduated from our program.”

Kaplan said the list of diagnoses that qualify for children to remain in government-subsidized hospice care include cancer, uncontrolled seizures, heart conditions and neurological issues similar to what Danyel is going through.

Many of them have genetic disorders, seizure disorders, cancer, leukemia, brain tumors, hydrocephaly (water on the brain), and brain damage from a lack of oxygen following near drownings, Kaplan said.

“A lot of our kids are on the transplant list, waiting for kidney, livers, hearts,” she said.

The children stay in the hospice program “until they either graduate off because all of their symptoms have been managed and they are no longer qualifying for our services” or the parents take them out, she said.

Many kids come on and off the service as needed, while “a lot of our kids discharge off service because they’ve gotten better,” Kaplan said.

Helping families cope

Home hospice care for the valley’s youths provided by 1Care includes a physician who makes monthly, face-to-face visits with a nurse and takes a head-to-toe assessment of each child to see if they need, for example, physical therapy.

“Instead of this patient having to go into the community and have to wait several months sometimes to get anything, our physicians can write referrals from the home and bring services into the home,” Kaplan said.

The hospice includes a social work department that sends workers out to make a social assessment of the emotional needs of the families, some of whom “have been just hit with the worst news that you could ever hear, that your child has a terminal illness,” Kaplan said.

“Not only are you going to deal with the financial burden, but now your heart is broken, right?” she said. “And you still got to work and you still have to keep your family together.”

The social workers then connect the families with resources available from local foundations and government agencies such as rental assistance from Clark County, she said.

Behavioral therapists, medications and access to medical-related equipment such as specialized beds, leg braces and wheelchairs, are also provided, Kaplan said.

“Some of the medications can be rather pricey, but our program is all-inclusive, so we can take care of the medications,” she said.

‘Loss is never easy’

While managing the kids who may live long after they age out of the program, staff members also experience the deaths of those in their care, Kaplan said.

The program’s bereavement department contacts the families of hospice children who have died at least once a month for up to 13 months, arranging for the grieving parents and siblings to talk to a social worker, a nurse, bereavement counselor or any 1Care employee who participated in the child’s life.

“We probably have on average one or two terminal children a month,” Kaplan said. “Some months none, some months three. And most of them are at home.”

In one case in May, the parents of an 8-year-old boy in the program and suffering from a rare type of liver cancer had their son removed from the hospice and checked into a hospital to manage his symptoms.

Kaplan, who got to know the boy’s family, was present in the room when he took his last breath.

“After you create a bond, that you love these families — I wouldn’t have missed it for the world,” she said.

“Loss is never easy,” she said. “There is a place to put it, though. And when you look at the gratitude part of being in someone’s life, to a parent, to a child, there really is no greater intervention.”

‘Like an army behind you’

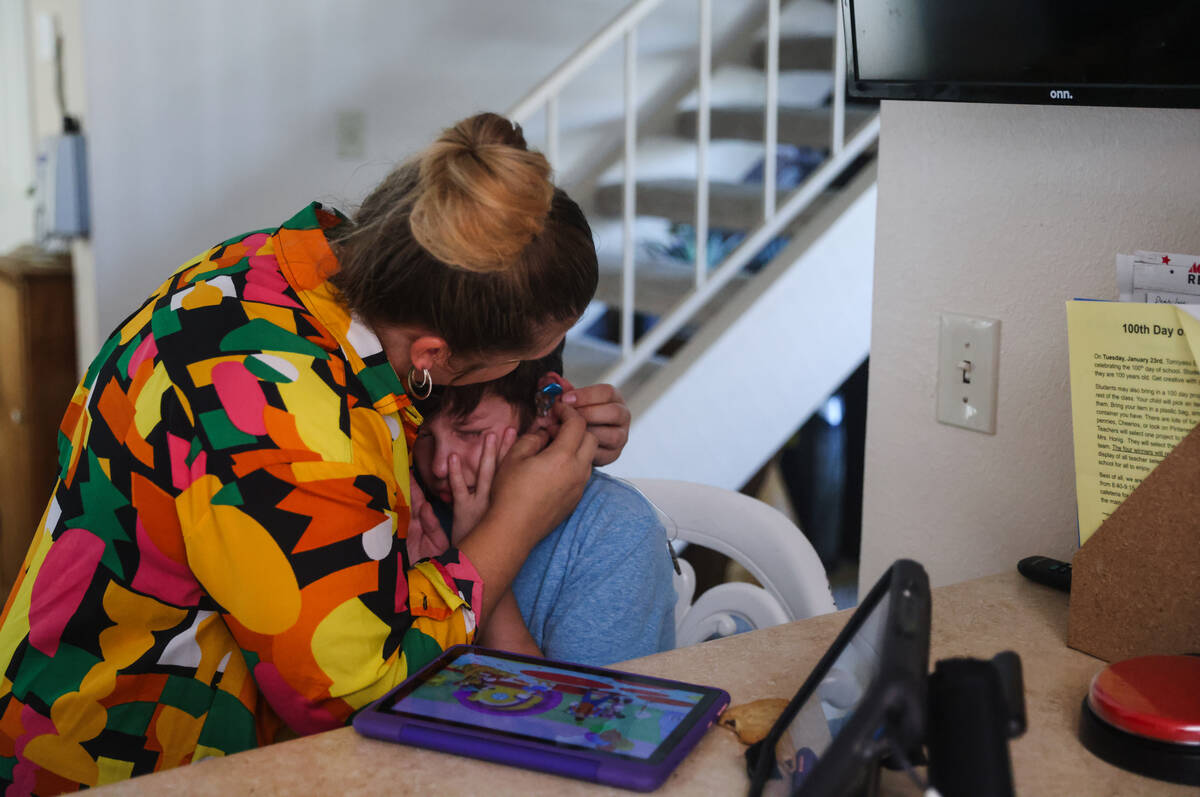

Tunea said she is grateful for the 1Care Hospice and the people who have helped both Danyel and his older brother, Jakob, who suffers from a chromosome 2 deletion, which the National Library of Medicine defines as “a chromosome abnormality that occurs when there is a missing copy of the genetic material located on the long arm of chromosome 2” and is often associated with intellectual disabilities and behavioral problems.

Jakob, who enjoys playing with graphics on a computer tablet, experiences autism-like behaviors and requires a lot of speech therapy, developmental therapy and physical therapy, Tunea said.

She said she also learned that something both kids share is a rare genetic heart condition that could cause them to suffer from cardiac arrest.

For her sons, the 1Care’s palliative hospice program helps “with the medication, regimens, pain management and the emotional part that goes along with that,” Tunea said.

Rather than an “end of life” concept, Tunea sees it “more like a teamwork, a support care system, like an army behind you because it’s too hard to do this on your own.”

“We’re a strong family, but I’m even stronger because I have that team behind me, and they’re willing to do anything.”

Contact Jeff Burbank at jburbank@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0382. Follow him @JeffBurbank2 on Twitter.