Las Vegas federal judge Lloyd George laid to rest

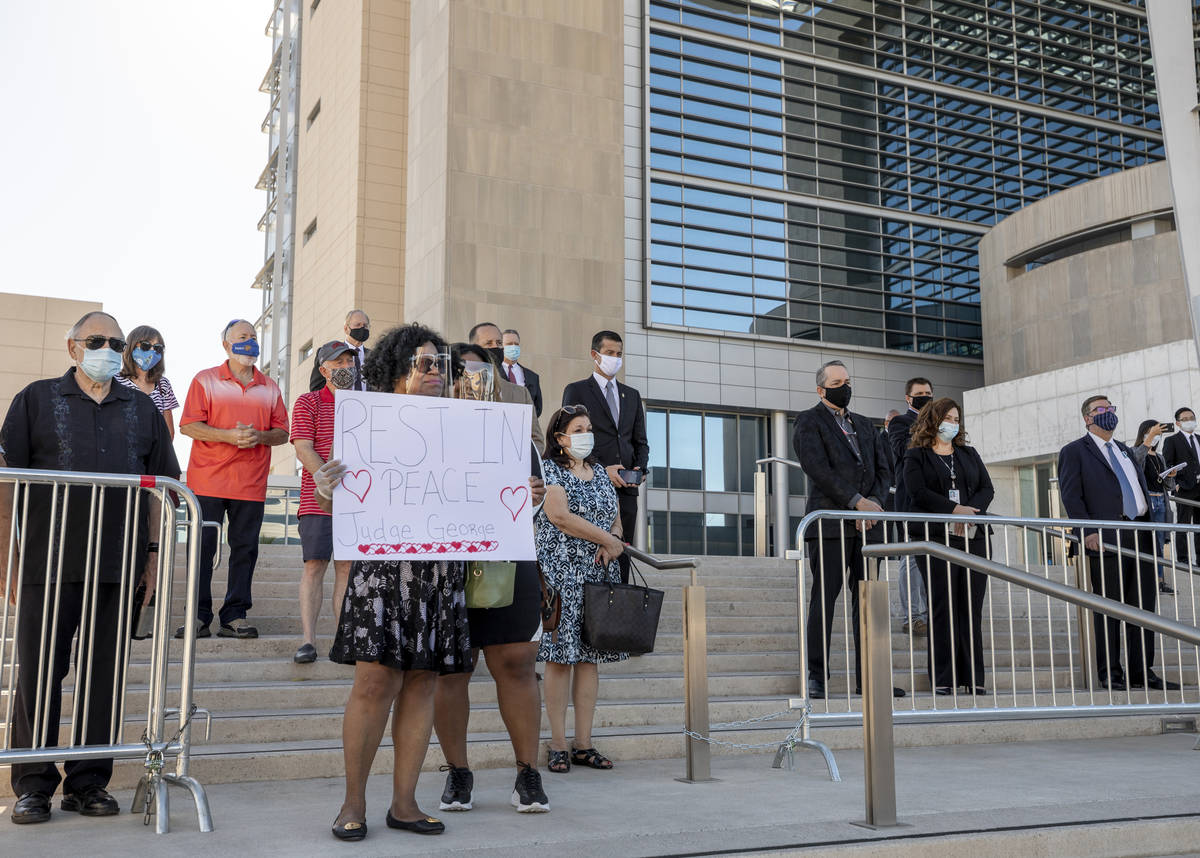

Johnnie Rawlinson stood atop the steps outside the Lloyd D. George U.S. Courthouse on Saturday, watching as a funeral motorcade stopped along Las Vegas Boulevard.

Inside the white hearse behind four police motorcycles lay the body of the man for whom the downtown Las Vegas building was named, a man she considered a friend.

George, who died earlier this month at 90, helped pave the way for her to become the first Black woman to sit on the U.S. 9th Circuit Court of Appeals.

“He encouraged me,” she said. “He’s was a pioneer in the local community and had a willingness to mentor lawyers.”

Rawlinson held up a sign that read simply “Rest in Peace Judge George” and waved as George’s family stepped out of their vehicles and greeted the crowd.

Because of pandemic limitations, George’s family kept his funeral services mostly private inside a chapel of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints on West Charleston Boulevard.

They remembered the man who carried a lifelong passion for the law, unconditional love for his family and an everlasting devotion to his faith.

They spoke of his hard work, high-minded legal lectures and family ski trips to Utah, where he was known as “The Black Avenger” on the slopes. They paid reverence to his legacy in court systems around the world and his smooth jump shots on the basketball court. They remembered how he had encouraged them.

“He just made people feel like they could do anything,” his granddaughter Marie Howick said. “Just by living his best life, he really impacted people in ways I don’t think he realized.”

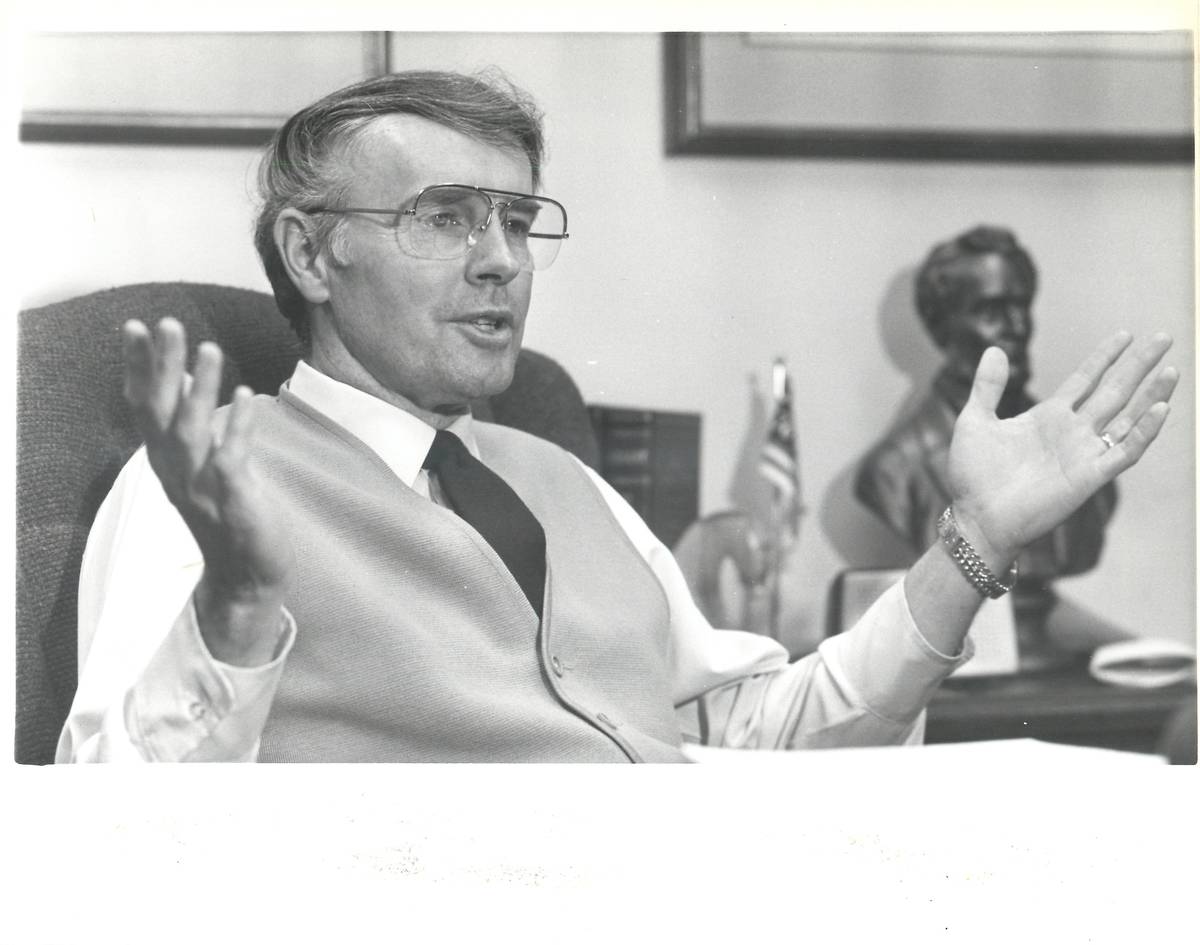

George, raised in Las Vegas, worked as a lawyer in private practice before being named to the U.S. Bankruptcy Court in 1974. He was appointed to federal court by President Ronald Reagan, replacing retiring federal Judge Roger Foley in 1984. Six years later, he was named chief federal judge for Nevada.

Starting in 1993, he joined the International Judicial Relations Committee to discuss constitutional issues and court structure in Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union.

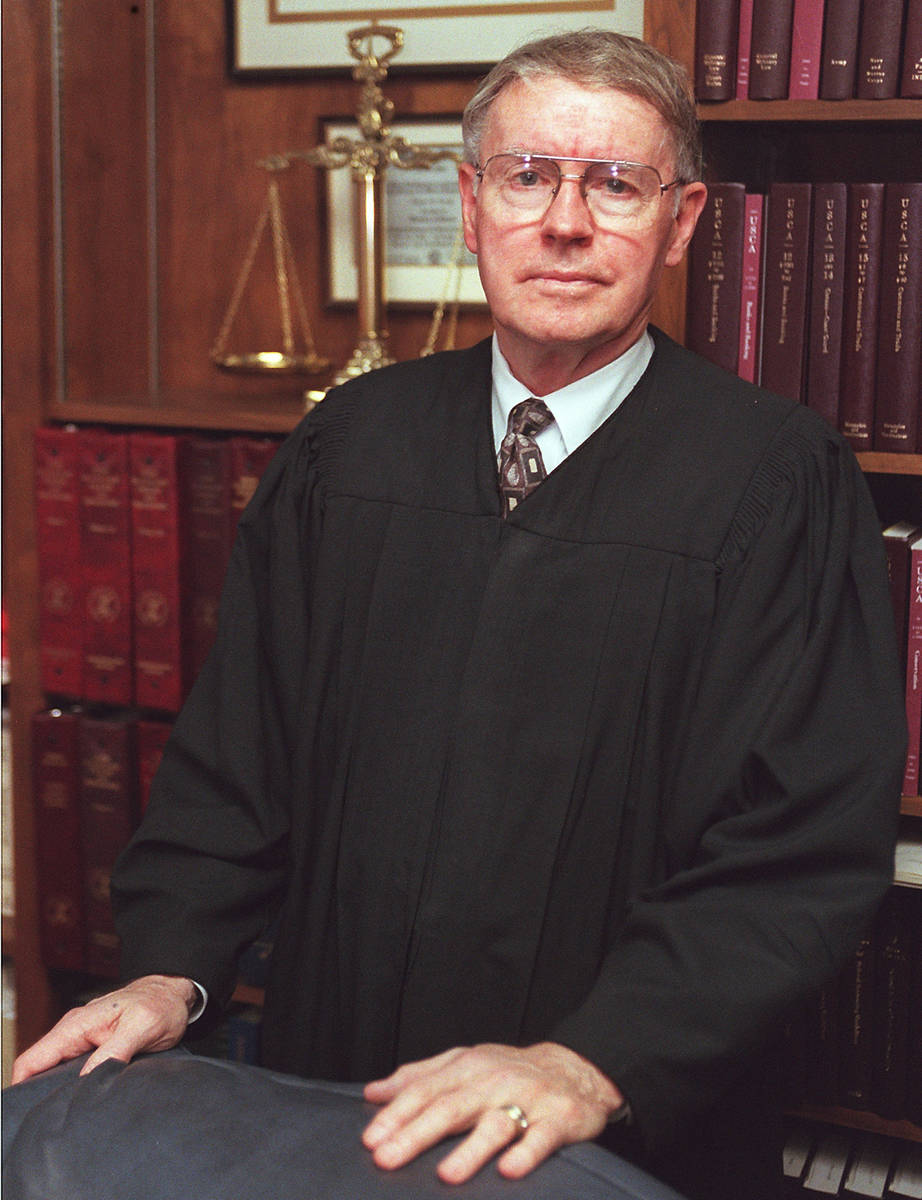

In September 1998, the House of Representatives followed the Senate’s lead and approved a bill to name the courthouse at 333 Las Vegas Blvd. South after him. The structure, with its articulated column and black and white granite benches under a massive steel awning, opened in 2000.

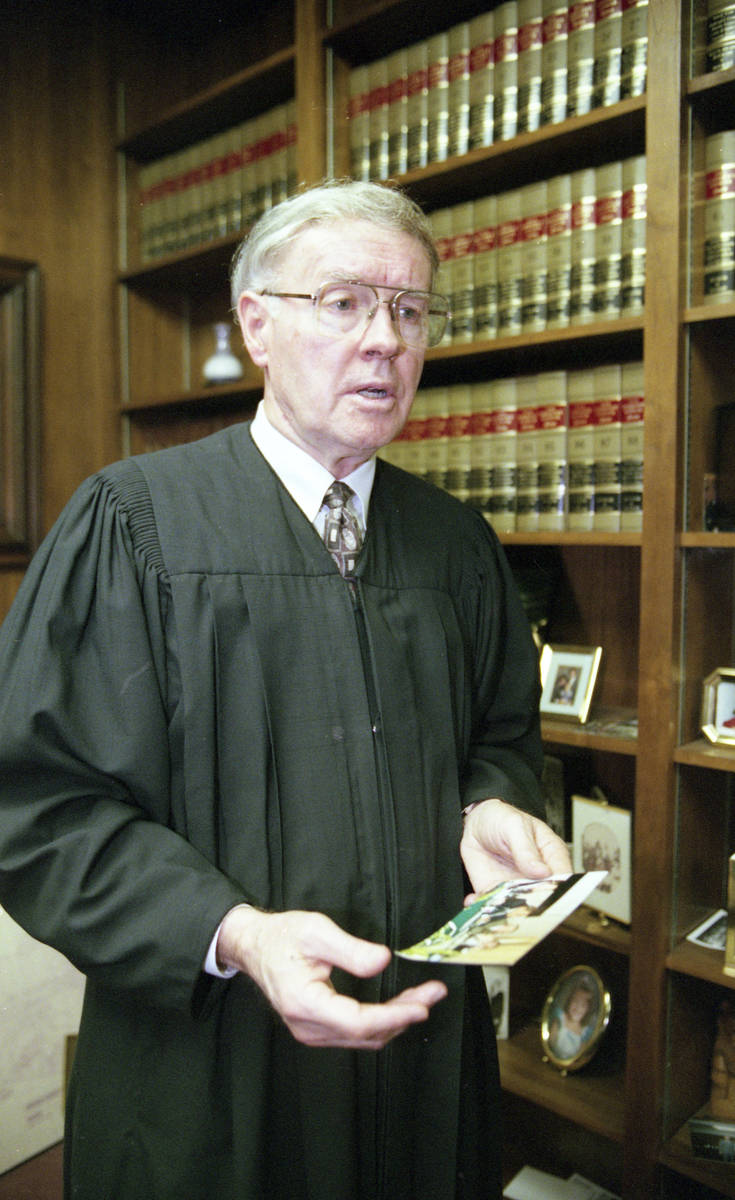

Even in his later years, Lloyd George’s legal mind remained sharp, said his son, Stephen George, a Henderson justice of the peace.

On Saturday, the younger George recalled a European trip the two had taken to visit the Estonian Supreme Court about eight years ago.

Stephen George had asked lawyers from the U.S. Department of State to keep an eye on his father, as signs of dementia had emerged.

But then his father began to speak to the judges.

“I was blown away,” Stephen George said. “It was unbelievably amazing. I actually thought it was a miracle. I sat there and watched my dad, like the most skilled surgeon, going through the law precisely, specifically, in great detail and clarity on aspects of the law and the legal and judicial process. I had never seen anything like that before.”

Lloyd George remained a Senior U.S. District Judge until his death.

Markers of some of his many achievements sat on a table near the entrance of the chapel on Saturday — a Presidential Citation, a Boy Scouts of America Silvers Beaver Award, a glass replica of the courthouse, and a book of his judicial opinions.

In the early afternoon, the small crowd rose as his grandsons carried away his casket, draped in an American flag.

George is survived by his wife, LaPrele, four children, 12 grandchildren and 10 great-grandchildren.

He was laid to rest at the Palm Eastern Mortuary & Cemetery.

Along with Rawlinson at the downtown courthouse, retired U.S. District Judge Philip Pro watched as George’s body was led away from the courthouse for the last time, knowing that his impact on Nevada’s legal community would remain.

Pro called George the “court historian” who “saw it grow” and “treated everyone with great respect.”

Rawlinson echoed the sentiment.

“He was so humble, he was always willing to talk to individuals,” she said. “He wanted to hear about people’s life stories.”

Contact David Ferrara at dferrara@reviewjournal.com or 702-380-1039. Follow @randompoker on Twitter. Staff writer Alex Chhith contributed to this report.