Las Vegas festival celebrates, honors black history

When Dr. James McMillan became the first black dentist in Las Vegas in 1953, he wasn’t allowed to stay at a Strip hotel.

Seven years later, McMillan, one of the first presidents of Las Vegas’ chapter of the NAACP, would lead the successful effort to end such segregation in the city.

On Saturday, McMillan’s only daughter, 73-year-old Jarmilla Arnold, accepted an award honoring her father at this year’s Black History Month Festival at the Springs Preserve.

“I certainly appreciate the fact — and my family appreciates the fact — that he’s still remembered,” Arnold said of her father, who died on March 20, 1999.

Each year the festival, which celebrated its 10th anniversary Saturday, honors a local leader who made a difference in the community, said Corey Enus, the festival’s coordinator.

Enus spoke of McMillan, whom he called “the pioneering doctor,” and the role he played.

“When he got here, Las Vegas was the Mississippi of the West,” he said. “His shoulders are those that we stand on today. Without him we wouldn’t be able to be here right now.”

Black history should be celebrated as a chance to teach today’s children about those that came before them, Arnold said later.

“It’s important to recognize those people who opened the door for the rest of us,” Arnold said as she sat in front of the festival stage. “Without them we wouldn’t be sitting in the Springs Preserve.”

’Great cultural wealth’

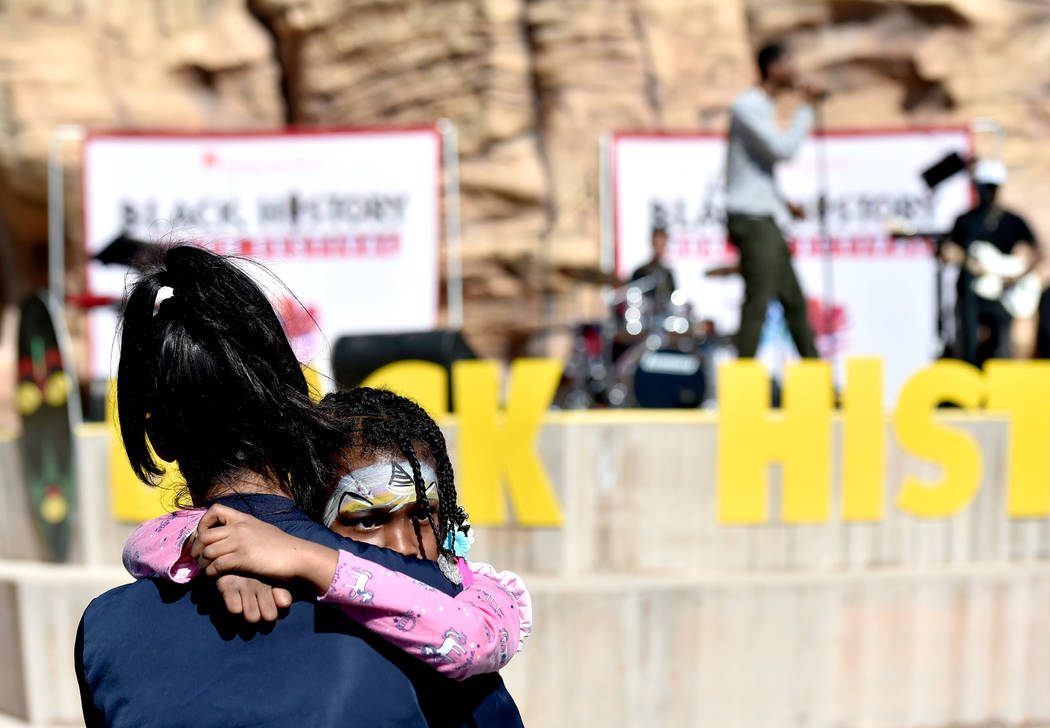

In addition to honoring McMillan, the festival featured performances from local black musicians, artists and authors, as well as face painting, carnival games, crafts, food and booths selling colorful clothes, all to celebrate black history.

“Black History Month is something that’s significant not just for the African-American community, but for the entire community at large,” Enus said. “We have a great cultural wealth here in this community, and the people who helped shape the history of our city are right here, still living in our city, and we want to pay homage to those people.”

Gospel music echoed throughout the outdoor Springs Preserve amphitheater as children ran around with painted faces and handmade hats. Respect — the theme for this year’s festival —was spelled out in large letters near the stage, and at times Aretha Franklin’s iconic voice could be heard over the festival’s sound system.

“I enjoyed all the stands and promotions and seeing the live artists perform,” said 48-year-old Cheryl Jackson, who attended the festival with her husband and two daughters — Gabby, 7, and Alex, 8 — who both proudly displayed the hats they made.

Remembering and learning

Alex said her favorite part about the festival was making a drum. She said she learned about Black History Month in school. Rosa Parks was her favorite person to learn about because “she was standing up for black people and not losing her seat,” Alex said.

Jackson said it was important for her to celebrate Black History Month because “it helps us remember the past and how we got all the achievements we have now.”

Racquel Watson, 43, said it’s a tradition to bring her 3-year-old son, Justin, to the festival every year. She said the two enjoyed meeting local author Brittany Green, who read her book “Little Black Girl” to the kids.

“That was exciting for us because Justin is an author himself actually,” she said, adding that she illustrates and helps Justin write books about the two of them traveling together. “We write about this little black boy that travels all over the world.”

Watson said it’s important to celebrate Black History Month so people can learn about different cultures and their own history.

“Just to learn what our ancestors went through, accomplished, their struggles, their triumphs, is important so we don’t repeat the same mistakes and so that we can move forward as a nation and as a people.”

Contact Katelyn Newberg at knewberg@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0240. Follow @k_newberg on Twitter.

Historic Moment

In March 1960, Dr. James McMillan, then-president of the Las Vegas NAACP chapter, sent a letter to then-Mayor Oran K. Gragson, giving him 30 days to desegregate the city. If he did not, the chapter planned a peaceful protest on the Strip calling for blacks to be allowed to enter casinos through the front door.

"There was a meeting that Saturday morning, March 26," Claytee White, director of oral histories at UNLV, said in a Review-Journal article last month about the Civil Rights Film Fest. "It was the headlines of the Sun newspaper. The photo on it shows the leaders of the city sitting around a table in the Moulin Rouge. The police chief, the mayor, the governor of the state, publisher of the Sun newspaper, black leaders were all there. They made an agreement that evening that hotels would grant African-Americans access to public accommodations. On March 26, 1960, integration took place in Las Vegas."