Mob Museum offers flashy exhibits, gory stories

Think of it as all the excitement of life in the mafia with none of the annoying prison terms or gunshot wounds.

That's what organizers of the National Museum of Organized Crime and Law Enforcement, aka the Mob Museum, want to deliver when they open their doors to the public today.

The museum is supposed to tell visitors the truth about notorious mobsters in American history and the cops, prosecutors and undercover agents who beat them back.

It's also expected to juice visitation to a formerly forlorn part of downtown Las Vegas that's betting a nationally recognized museum will attract as many as 300,000 new visitors annually.

Whether the $42 million museum at 300 Stewart Avenue can meet lofty expectations remains unclear.

But a sneak peek at exhibits provided to local media on Monday showed visitors will experience flashy displays, gory stories and details about mob life that are unfamiliar to most people who aren't wiseguys or FBI agents.

"This is very much designed as an experience in which people get to do something," said Jonathan Ullman, executive director of the museum.

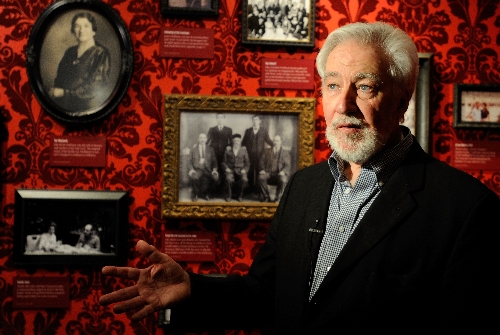

The exhibits cover three floors of the former U.S. Post Office and Federal Courthouse building dedicated in downtown Las Vegas in 1933.

Although it was previously best-known as the only building in Las Vegas recognized as having historic value on a national level, many of its new exhibits are flashy and modern.

On the third floor, where visitors are expected to start their trip through the history or organized crime, the centerpiece of an exhibit on the history of Las Vegas is a series of touch screens embedded in a tabletop in a replica of the old Arizona Club, an early Las Vegas saloon.

It's next to another exhibit that combines new technology with an old-time artifact, the reassembled, bullet-scarred wall that was the backdrop for the "St. Valentine's Day Massacre," a 1929 mass murder of seven gangsters in Chicago at the hand of rival gang members, some of them dressed as cops.

The wall is behind glass onto which is projected video about the infamous shooting. It's the centerpiece of a section of the museum that deals with Prohibition.

"This is the time period in which these gangsters acquired immense wealth," Ullman said.

The most elaborate exhibit in the museum is also a multimedia experience and is on the second floor in the room that gives the museum building its historical significance.

That is the courtroom where in 1950 former Sen. Estes Kefauver of Tennessee held one of 14 hearings into organized crime in America. The room is restored to how it looked when Kefauver held the hearing in Las Vegas. It's outfitted with audio and video equipment that tells the story on a large projection screen.

The Las Vegas hearing wasn't televised, but others in the series were, and the video combines real footage with actors who use hearing transcripts.

The hearings were the subject of deep, national interest for as many as 30 million people who watched them on television, about 20 percent of the entire national population at the time.

"Literally businesses shut down when these hearings were on," said Ullman, explaining how the widespread interest managed to fuel the growth of Las Vegas by reducing competition for gambling and other vice spending elsewhere.

"There was significant public backlash," against organized crime, he said. "States that were considering legalizing gambling chose not to."

Other exhibits delve into the mob's infiltration of Las Vegas casinos from the 1960s into the 1980s.

Exhibits explain how mobsters skimmed money from casino count rooms and sent it back to bosses in the Midwest.

The whole process is summed up nicely by former casino operator Carl Thomas, who during a 1978 meeting with mob boss Joe Agosto explained how the skim worked, unaware that the FBI was listening in.

"The guys go back there and snatch the cash," Thomas can be heard saying on a recording played in the museum. "Now the bad part about that system, if they tell you they're taking $2,000 a day, they could be taking $2,400."

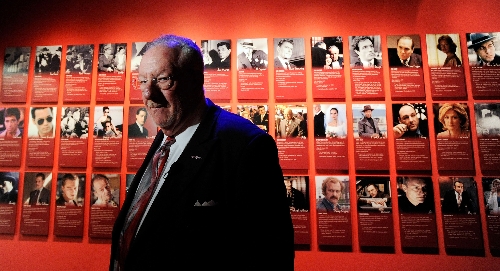

Additional exhibits focus on memorable police and FBI agents and on how organized crime is depicted in movies.

Ellen Knowlton, former FBI special agent in charge of the Las Vegas division and president of the board of 300 Stewart Avenue corporation, the nonprofit entity that will operate the museum, said the idea is to portray the reality of organized crime as accurately as possible.

She disputed the notion that Las Vegas was better off when casinos were under mob control and said that, in fact, the mob bosses were holding back progress that didn't catch on until they were driven out.

"When organized crime people are controlling a segment of the economy, honest, decent people are shut out," Knowlton said. "Anytime you have a business that is getting skimmed, it can't reach its full potential,"

Others, including Las Vegas Mayor Carolyn Goodman, saw the era through rosier glasses.

Goodman, who is married to former mayor, former mob lawyer and Mob Museum proponent Oscar Goodman, repeated a statement -- debunked as myth by the museum-- that mobsters only hurt other mobsters. She said that before a small number of corporations controlled nearly all the business on the Strip, there was more competition, which was good for Las Vegas.

"The casinos were privately owned; it was truly competitive, casino to casino, to do a better job than the casino next door," Goodman said.

Contact reporter Benjamin Spillman at bspillman@reviewjournal.com or 702-229-6435.