Mosquito species ‘exploded all over the valley’; What can the health district do?

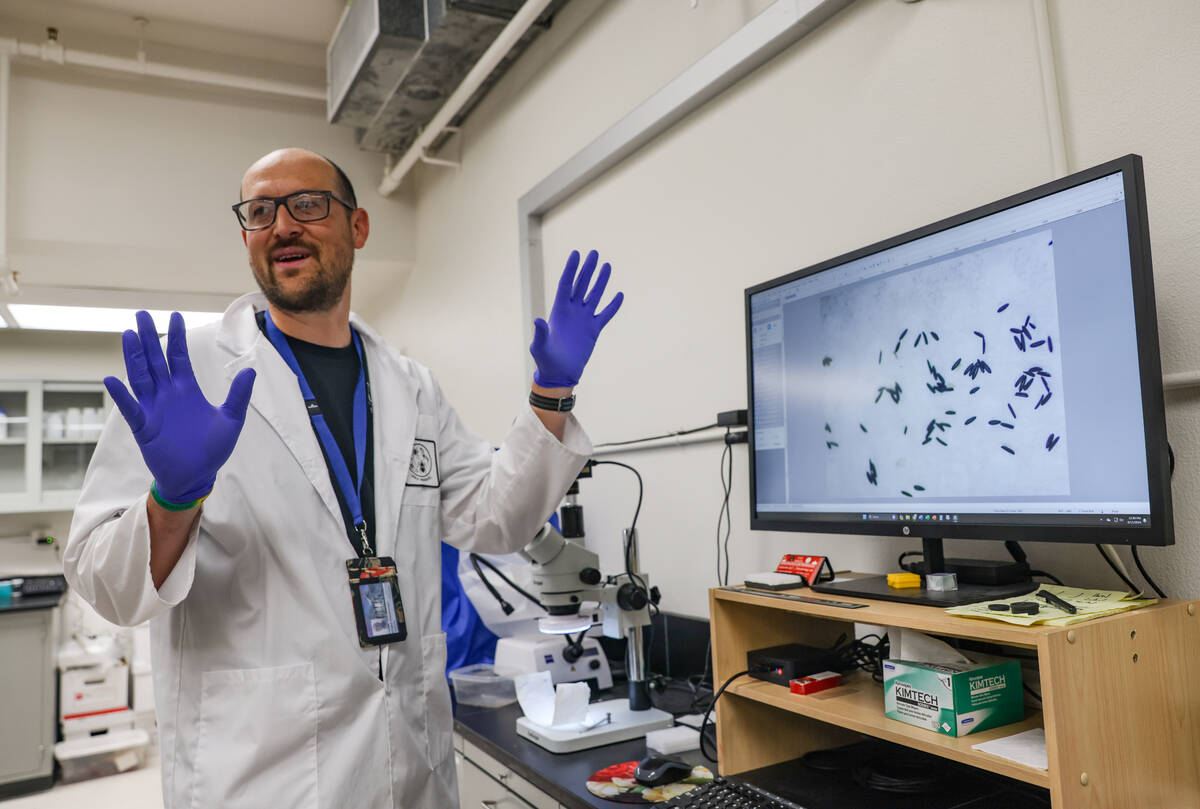

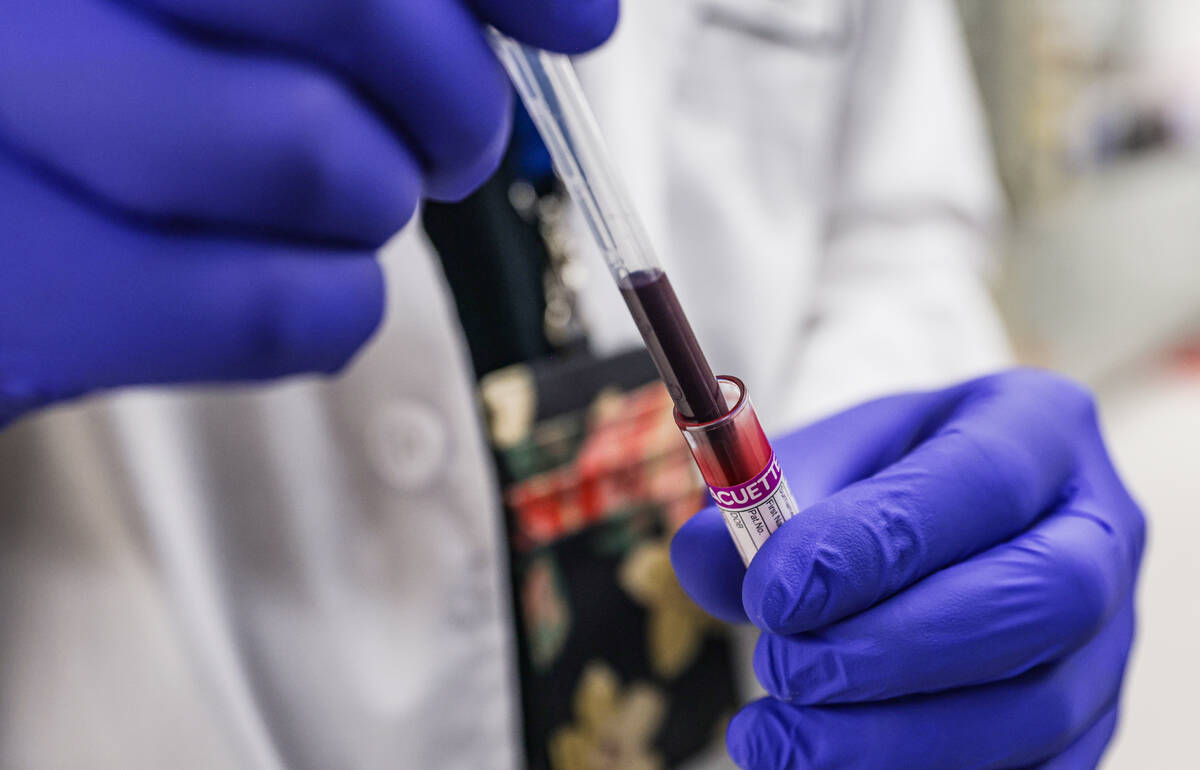

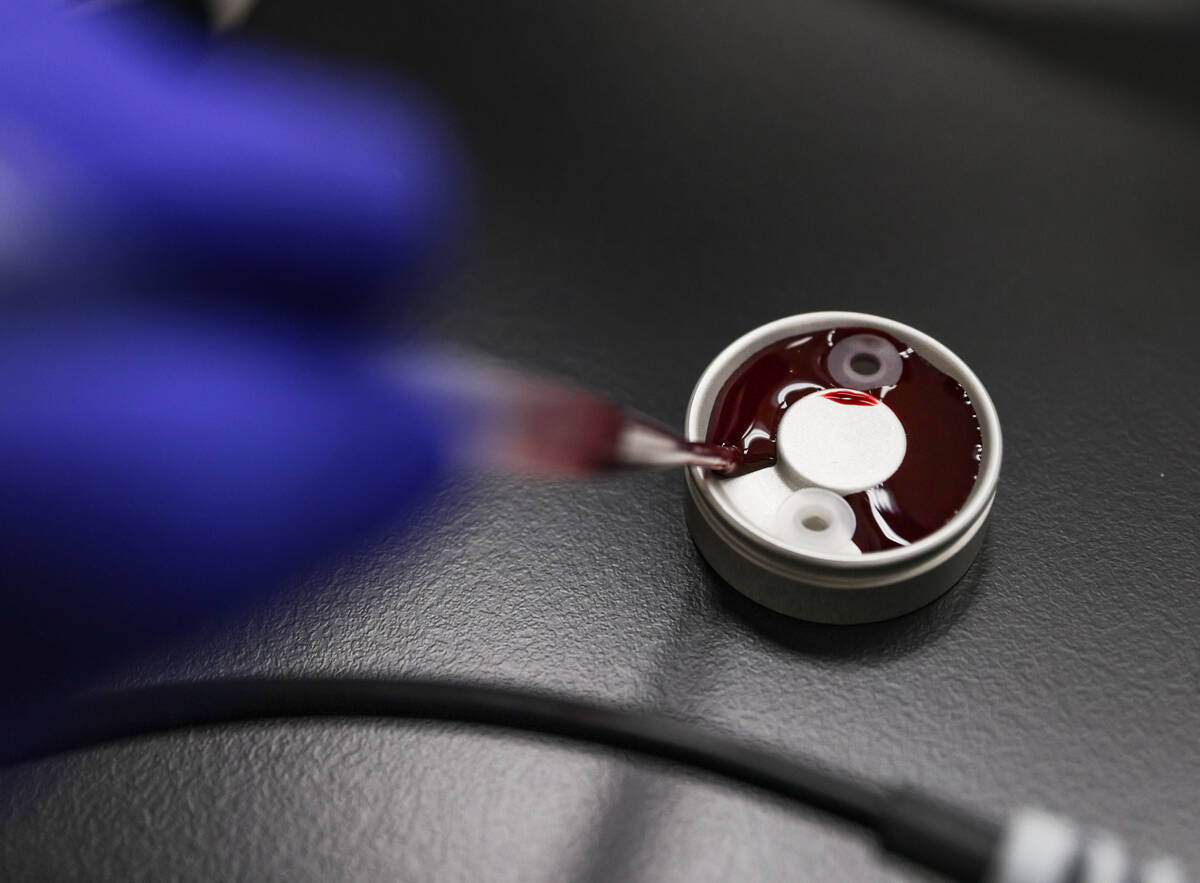

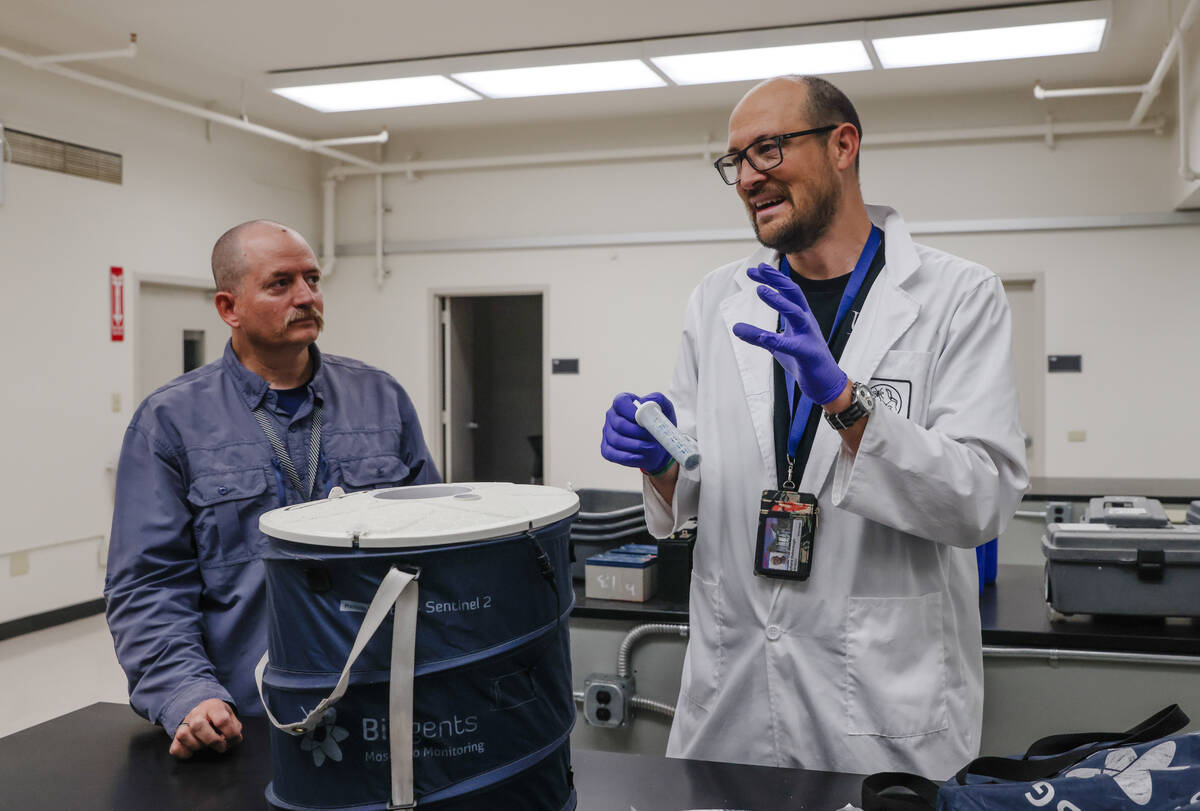

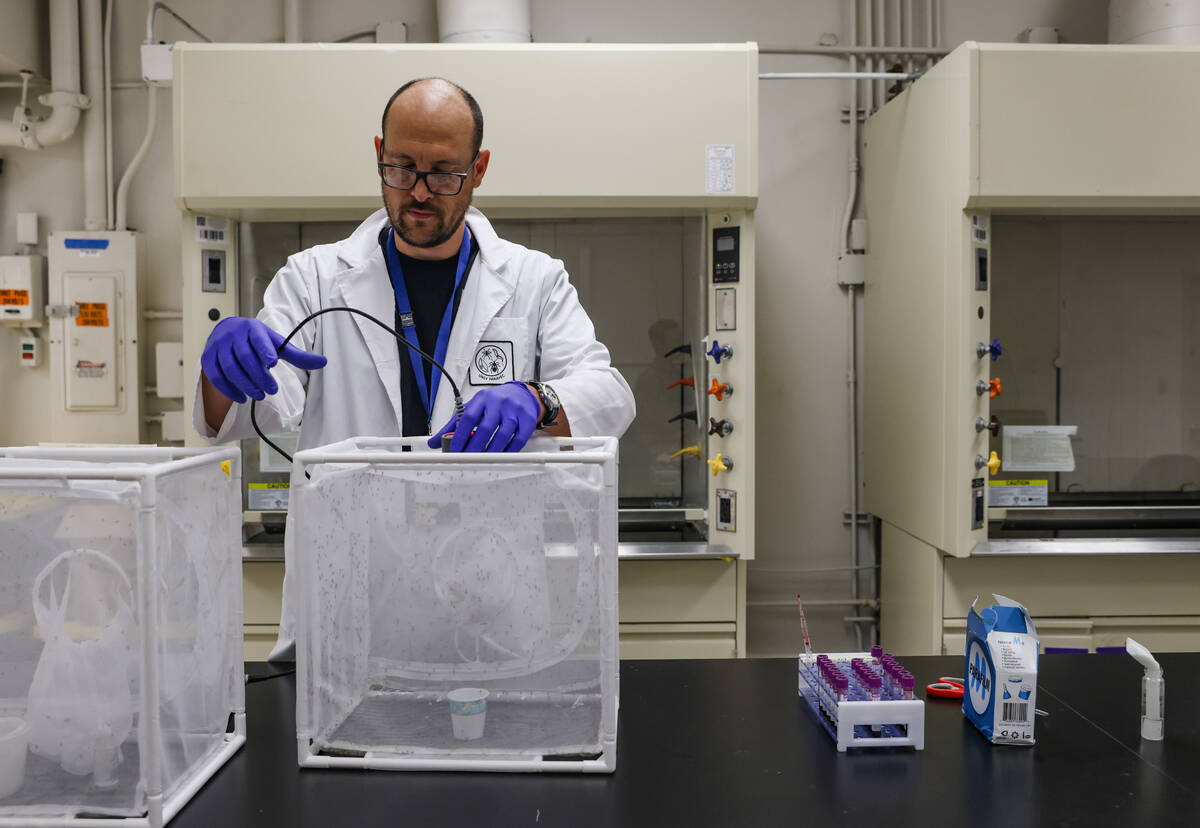

Richard Oxborough plucked a vial of human blood from the rack on his lab bench.

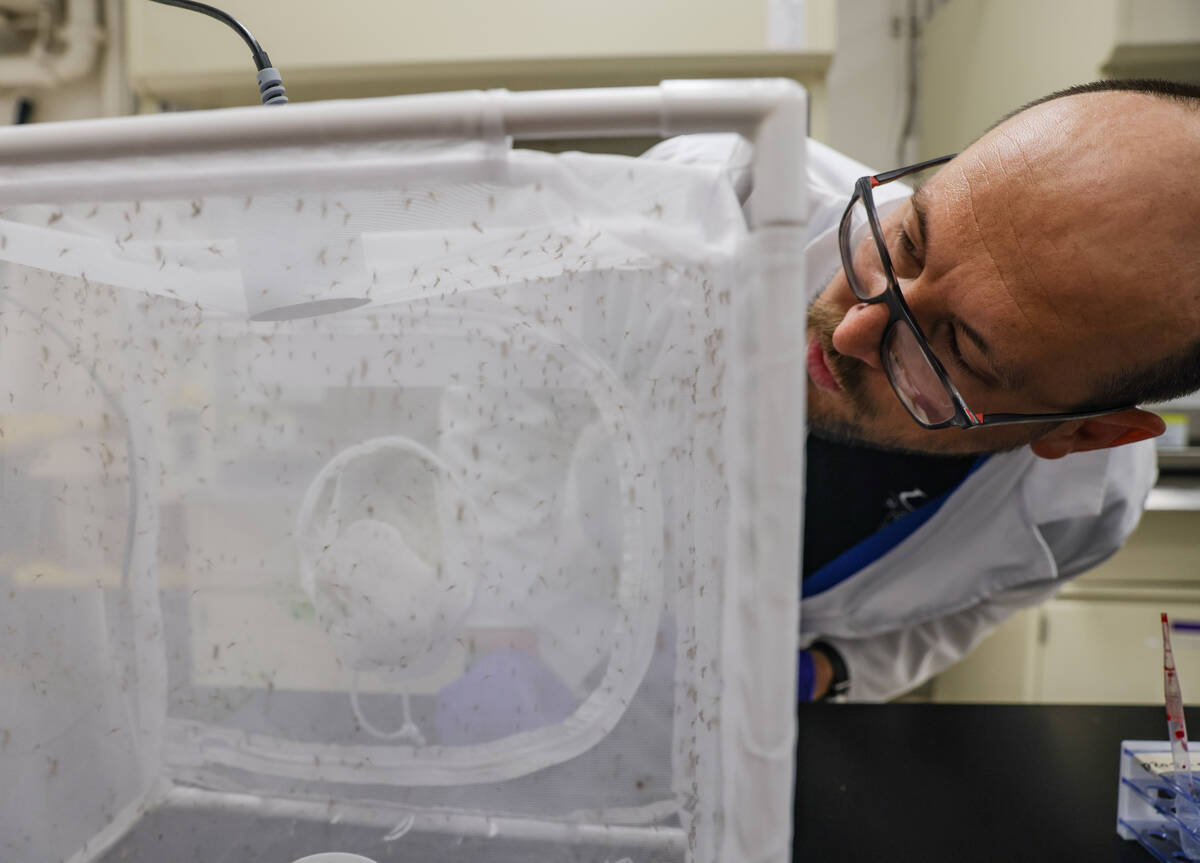

The UNLV researcher warmed the blood and fed it to a colony of mosquitoes. The critters won’t be quite as voracious as normal because Oxborough didn’t have the chance to starve them, he quipped.

Oxborough studies arboviruses — viruses transmitted by the bites of mosquitoes, ticks and other arthropods. This June, a larger than normal amount of local mosquitoes have tested positive for West Nile virus.

Chad Cross, a UNLV professor and Oxborough’s colleague, said they were raising mosquitoes for insecticide testing. The results will be sent to the Southern Nevada Health District, which can use them to devise mosquito control strategies for Clark County.

While the health district doesn’t perform mosquito control, it may have to at some point because of the threat of West Nile and other viruses, the researchers said.

“The desert is not generally a good climate for mosquitoes. It’s very dry,” Oxborough said, adding mosquito larvae won’t survive without water.

The district formed a mosquito surveillance program after West Nile was first identified in the county in 2004.

West Nile is the leading cause of mosquito-transmitted disease in the continental United States, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Most people infected with the virus have no symptoms.

About 1 in 150 infected people develop neuroinvasive West Nile disease, which can cause fatal swelling in the nervous system.

In the past decade, 44 human cases of neuroinvasive West Nile have been reported in the county. A West Nile outbreak occurred in 2019, when 34 neuroinvasive cases and two virus-caused deaths were reported.

Vivek Raman, an environmental health supervisor at the district, said one West Nile case is “too many.”

‘We just never have seen activity this early’

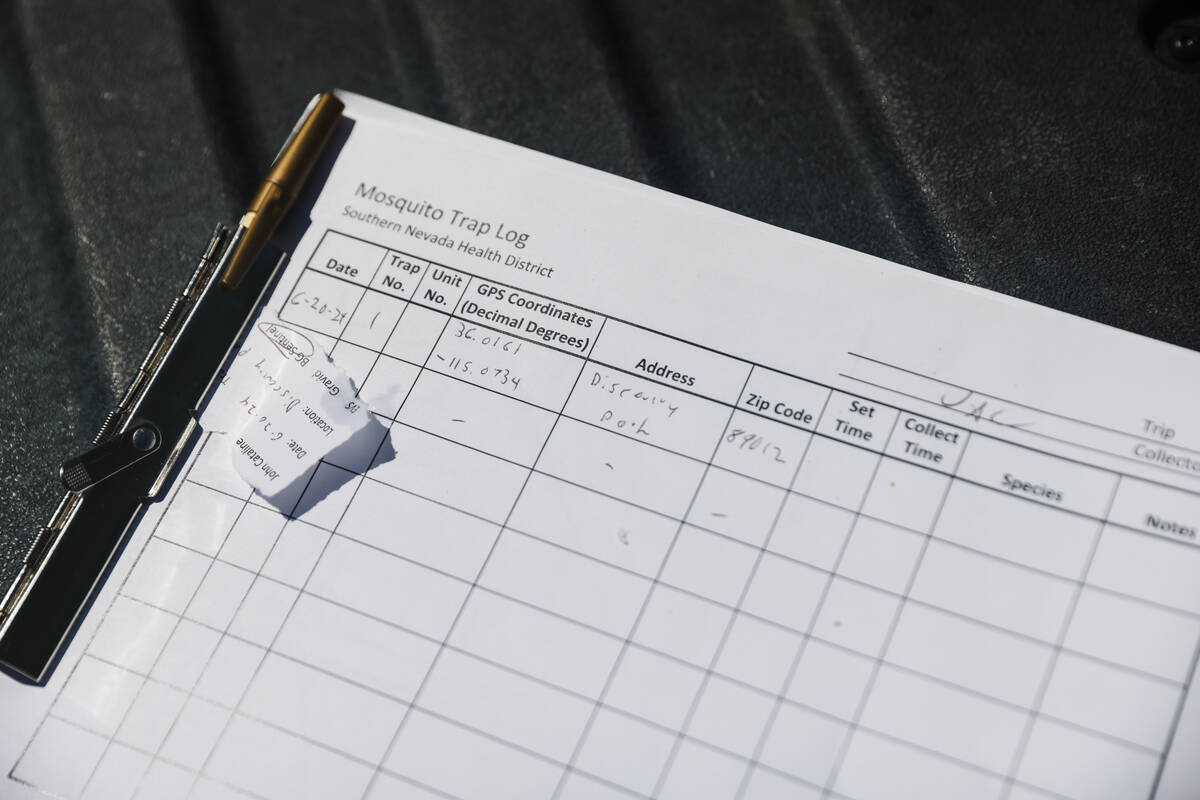

The district monitors local mosquitos for diseases by trapping them each April to October.

When the district retrieves a trap, it’ll divvy up captured mosquitoes by species into pools, which are then smashed up and tested for diseases.

As of June 14, the district has submitted 1,553 pools for analysis this year, and 169 have been West Nile positive. Those 169 pools came from 25 ZIP codes. No human cases of West Nile have been reported as of Monday.

“Typically, a few weeks after you see West Nile positive mosquitoes, you can start having human case reports,” Raman said.

From 2020 to 2023, the district tested over 12,000 mosquito pools for diseases. Only 42 were positive for West Nile.

In 2019, the year of the outbreak, 268 of the 2,262 pools tested were positive for the virus. At the end of June 2019, seven pools were positive for the virus, Raman said. The surge of West Nile positive pools in 2019 occurred in late July and August, he added.

“We just never have seen activity this early in the season,” Raman said of this year’s early arrival.

‘Most important emerging’ mosquito-transmitted threat

In addition to West Nile, the district tests mosquitoes for St. Louis encephalitis and Western equine encephalitis. The last time the county had a reported case of St. Louis encephalitis was 2016. No human cases of Western equine encephalitis have ever been reported.

Raman said the “most important emerging” mosquito-transmitted disease threat in Southern Nevada is an invasive mosquito species called Aedes aegypti.

The species was first identified in the county in 2017. In 2022, Aedes aegypti were found in 12 ZIP codes. They spread to 43 ZIP codes in 2023.

“It just exploded all over the valley,” Raman said.

As Aedes aegypti spread, the district received more mosquito complaints. The district had 99 complaints in 2022. In 2023, it had 735. The district has received more than 250 complaints so far this year, Raman said.

Aedes aegypti are aggressive daytime biters. Culex quinquefasciatus, the most-trapped mosquito species in the area and the variety that spreads West Nile, feed on birds and humans usually at twilight.

According to the district, Aedes aegypti are a threat because they can transmit diseases, such as dengue, chikungunya, yellow fever and Zika virus.

Raman explained why the district is concerned about dengue, for example.

PBS reported over 4.5 million people, mostly in Latin America, have been infected this year with dengue, which can be fatal.

A “fair number” of Las Vegas’ 40 million yearly visitors come from areas “endemic” with dengue, Raman said. If a local mosquito bites someone with a travel-associate case of dengue, the disease could start spreading here, he added.

What can the health district do?

Oxborough said mosquitoes can survive the arid conditions here because of human constructions such as swimming pools, golf courses and structures used for irrigation and drainage. Humans create mosquito habitats when watering their lawns and leaving clutter in their backyards before rainfalls.

“The water here evaporates generally really quickly, but it doesn’t need to stay there for long for a mosquito to complete its life cycle,” Oxborough said.

Cross said the ideal breeding ground of a Culex mosquito is a “stinky,” abandoned swimming pool. Aedes mosquitoes prefer to lay eggs in tiny containers.

Since the health district doesn’t perform mosquito control, it relies on jurisdictional counterparts to combat mosquito-transmitted diseases. These counterparts include local public works, code enforcement and park departments.

If the district learns a broken park irrigation system has become a mosquito breeding ground, it will make a report to the parks department, which can fix the problem. If the district finds out a stagnant swimming pool has become a breeding ground, it will notify the proper code enforcement department, which has the authority to clean up the pool.

Clark County Vector Control, which does not do mosquito surveillance, does perform mosquito control. Clark County recently purchased a six-bladed drone, which can be used to drop insecticide on mosquito breeding grounds.

The health district also keeps in touch with its clinical network. Since many mosquitoes tested positive for West Nile, the district sent out a public health advisory June 10 informing health care providers they may start seeing patients with West Nile infection symptoms.

Oxborough said many cities in the Southwest have entities that perform both mosquito control and surveillance, including Phoenix and Salt Lake City.

A Salt Lake City resident can ask his “mosquito abatement district” to stock a pond on his property with mosquito-eating fish. Control sometimes involves spraying droplets of insecticide into the air from a pickup truck, Oxborough added.

According to Oxborough, entities that perform mosquito control as well as surveillance regularly do insecticide testing. Such testing has never been done in Las Vegas before now.

Oxborough said he was working with the district on insecticide testing because the UNLV researchers and the district anticipate the district might need to do mosquito control in the future.

Contact Peter Breen at pbreen@reviewjournal.com.

5 tips to minimize exposure to mosquito bites

— Avoid spending time outside when mosquitoes are most active, at dawn and dusk

— Use insect repellents containing DEET, Picaridin or oil of lemon eucalyptus when outdoors

— Wear pants and long-sleeved shirts and spray repellent on clothes when outdoors

— Make sure doors and windows have tight-fitting screens without tears or holes

— Prevent breeding by eliminating areas of standing water

Southern Nevada Health District