Nevada’s legal purgatory: Paroled prisoners stay behind bars

The case of Russell Yeager isn’t a whodunit or a claim of wrongful conviction.

Yeager is, without a doubt, a murderer.

The mystery lies in what led to Yeager walking out of High Desert State Prison on Jan. 2, 2014 — more than 12 years after the Nevada Parole Board said he should no longer be behind bars.

Because in Nevada, being granted parole doesn’t mean you get out.

The parole board determined in 2001 that Yeager, 52, no longer posed the same risk to society he did as a rage-filled 15-year-old runaway who killed in cold blood.

For 13 years, Yeager asked the prison system, lawyers and the Nevada Supreme Court to give him what he had been granted. But nothing seemed to help.

Then suddenly, inexplicably, Yeager was out.

So why did the government decide Yeager was fit for release but not follow through for more than a decade? And more importantly, why are dozens more people — some convicted of nonviolent crimes — caught in the same legal purgatory?

It’s a conundrum that continually pops up in the Legislature. And it comes at a high cost to Nevada taxpayers: About $4 million a year to house and feed inmates the government determined should be let out.

Yeager — whose case is an extreme example of delays an inmate can face — is part of a parole backlog that is not only expensive but also puts the public at risk, according to criminal justice experts. Many of the inmates will serve their full sentence in prison, then be dropped back into society without supervision from a parole officer.

Through public records, interviews and correspondence the Review-Journal has found:

■ Some inmates are just too poor for parole. There is a limited amount of public funding available to help inmates pay rent at the state’s few halfway houses, leaving some stuck.

■ The parole backlog largely has been pushed aside by anyone with the power to do something about it.

■ The seemingly haphazard process could violate constitutional rights.

If Nevada leaders figured out how to get their backlog of paroled inmates out of prison, it could save millions and offer a fairer system on the surface. But one thing is clear in this mystery: With the legislative session underway, no one seems to have a plan to speed things up.

GRANTING PAROLE

Nevada’s 21 prisons, conservation camps and transitional facilities housed an average of 12,739 inmates a day last year. This year, the corrections department is authorized to spend $300 million on the system.

The Nevada Parole Board, in determining whether inmates are ready to rejoin society, takes the first step in cutting those numbers.

Prison sentences typically involve a range — say two years to four years, with the inmates eligible for release once they have served their minimum. The parole board then can deem prisoners eligible to serve the remainder of their sentence supervised by a parole officer.

The board considers the likelihood the prisoner will break the law again; the severity of the crime; the inmate’s criminal record; testimony from crime victims; the inmate’s history of violence, drug use or sexual deviance; and whether the prisoner has failed a previous probation or parole.

If the board grants parole — a privilege, not a right, according to Nevada law — the inmate must submit a plan for life on the outside to the Nevada Division of Parole and Probation.

And that’s where the system hits a snag. For one in three paroled inmates, something goes awry with the submitted plan and Parole and Probation officials won’t sign off. The inmates then wait, often for months or even years.

Those holdups result in Nevada taxpayers paying roughly $343,000 per month — or more than $4 million in an average year — to feed, house, guard and provide medical care for more than 300 people a year the state has decided don’t need to be in prison.

Last year, Nevada averaged parole backlog of 365 prisoners. The bottleneck would fill almost 70 percent of the Warm Springs Correctional Center in Carson City.

In July, Parole and Probation officials highlighted reasons for the problem during a presentation to a committee tasked with improving Nevada’s criminal justice system. Most were linked to administrative delays in submitting, evaluating and/or approving parolee release plans.

Numbers for last year — the only figures the state released — back those claims.

More than 75 percent of parolees awaiting release in 2014 were stalled by plan-related administrative delays. Most had either provided a “non-viable” plan or refused to submit one at all, or were waiting for approval of a potentially viable plan, officials said.

Parole officers investigate the inmate’s proposed parole address, check to be sure the inmate’s plan adheres to any requirements imposed by the board and monitors for new disciplinary action before signing off on a release plan.

About 10 percent of unreleased parolees had an approved plan but stayed locked up while awaiting indigent funding or approval to parole in another jurisdiction.

Around 5 percent of unreleased parolees had trouble finding a halfway house or faced placement complications stemming from their sex offender status.

Those numbers align with figures provided to the justice committee in 2014, and fit an overall trend of release-plan snags seen in recent years. Officials said more detailed statistics aren’t readily available.

Duane Tipton, 39, who pleaded guilty to lewdness with a child under 14, still doesn’t understand what — if anything — he did to be released to a Las Vegas halfway house in November.

He had been granted a second chance in 2012, after a parole violation landed him back in prison. He applied for indigent funding but was rejected because he had been given some of that money before, documents show.

Tipton then asked if he could move into a homeless shelter, according to handwritten prison forms he provided, but was told shelters are not allowed.

Exasperated, on June 6, 2013, Tipton wrote directly to the Department of Corrections, which manages indigent funding for parolees.

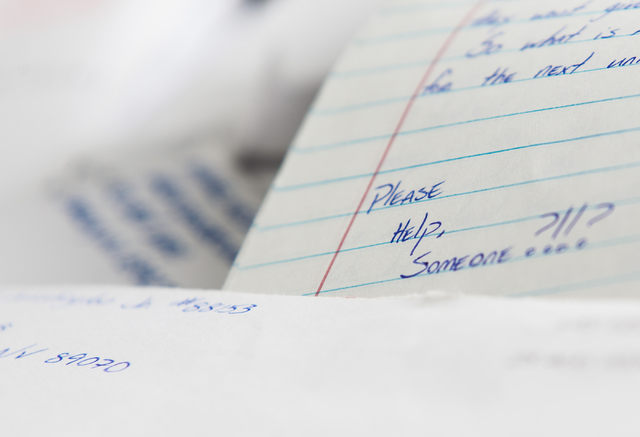

“So what you’re saying is I’m on parole but I have to spend it in prison because I have NO MONEY and no Family to help me or Friend to help me. Why do I have parole, shouldn’t you contact them and tell them I can’t leave. Can I put in a new plan to go out of state or is that a NO too? Is there any [halfway houses] that are free or don’t expect you to pay right then and there? I heard Salvation Army is free and accepts [sex offenders]. Is there any place that will help me pay for my [halfway house]. Please answer my question. Thank you!”

The response:

“Unfortunately you have no current options. Parole is a privilege not a right. You have burned your bridges (indigent funding is only available once). Salvation Army is no longer available.”

In September 2014, Tipton was told he would be released after picking a place at Siegel Suites, the Las Vegas weekly apartment complexes.

Then another letter came: Siegel Suites was no longer a parole option.

“Boom!!! My dreams were destroyed,” Tipton wrote.

But Tipton was released in November without being told why.

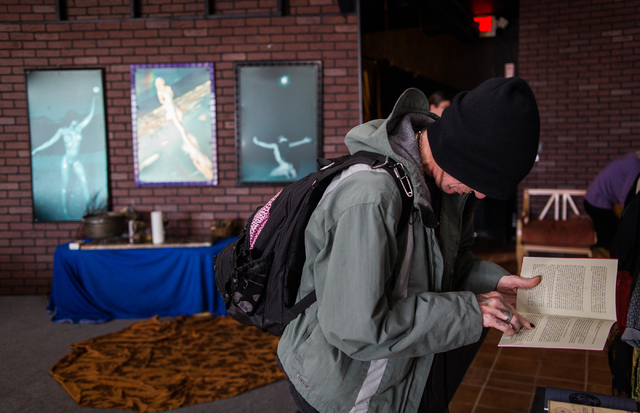

The state paid for two weeks at a halfway house, he said, but after that he was right where he had asked to be more than a year before: Homeless.

POVERTY AND PURPOSE

Martin Horn, a criminal justice lecturer at City University of New York, said dumping inmates onto the street is fundamentally unfair.

“It discriminates against the poorest and illiterate prisoners,” Horn said.

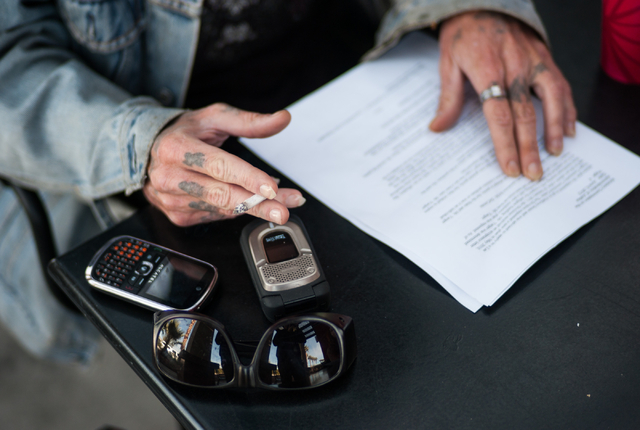

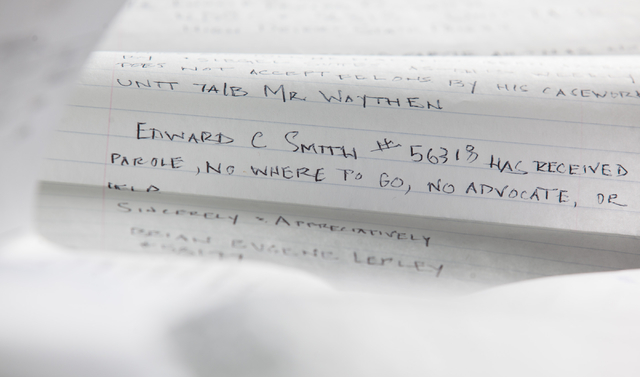

The Review-Journal reached out to dozens of inmates listed with the state as paroled but still in prison. Twenty-four wrote back, and a little more than half of them mentioned a lack of money as part of the reason they couldn’t get a division-approved release plan.

If inmates don’t have approved family or friends to live with, the division requires proof of ability to pay for placement in a state-licensed halfway house, transitional living facility or treatment center.

Parolees lacking viable options serve their maximum sentence.

Parole and Probation Capt. Dwight Gover said the division can help parolees get a “limited amount of funding” to hasten their prison exit. But applicants must meet criteria approved by the separate Department of Corrections.

In 2014, 378 inmates applied for that money. Only 113 applications were approved.

Money is limited. The Legislature appropriated $68,928 for fiscal 2014-15.

Corrections has turned away roughly two of every three applicants since 2012. The department chalked up denials to inmates’ failure to meet funding eligibility requirements.

To qualify, parolees must provide a birth certificate and an approved release plan three months before their release date. None of the 113 had more than two prior prison terms, and all provided a three-month history of prison bank records.

Other states have parole backlogs, but there is little national data about the problem, said Horn, who has worked in Pennsylvania and New York corrections systems for more than 45 years.

“What we’ve come to realize — and Nevada has to realize — is it’s in the state’s best interest that they take a purposeful approach for this process of re-entry,” Horn said. “The governor basically has to knock heads.”

Gov. Brian Sandoval said he was unaware of the parole backlog until the Review-Journal informed him, although he backed a proposal that brought the issue before the Legislature in 2013.

Corrections Director Greg Cox was then pushing to shift Parole and Probation from the Department of Public Safety to his purview. Sandoval included the change in his budget request. Cox pitched it to lawmakers as a way to cut costs and prevent recidivism.

The effort died after the Nevada State Law Enforcement Officers’ Association argued it would be more expensive, and Parole and Probation employees testified against it, saying Cox just wanted to sneak corrections officers a pay raise.

Sandoval said he pushed the proposal as far as it could go but moved on when it was voted down.

Parole’s place in Nevada is unusual. Many states make parole part of corrections. Others require an inmate’s release plan before the parole board even considers supervised release.

And in some states, the prison system makes release plans for inmates.

Not having united parole and corrections departments creates a challenge, Horn said, because separate agencies can have conflicting interests.

“The parole system wants to make sure when they accept someone on parole they have the greatest likelihood of success. On the other hand, the prison system for a lot of equally valid reasons wants people who have served their time to be released on time.”

Sandoval said he would look into the backlog but called it a “Catch-22.”

“Nobody wants to hold somebody longer than they need to be. It’s not in the state’s best interest to do that because of the cost, but there is a significant public safety issue there,” Sandoval said. “You can’t just release somebody into the community and say, ‘Good luck.’ You have to make sure they have employment, you have to make sure they have services, you have to make sure that they have a place to stay or they’re going to re-offend.”

Alvin Carter’s case shows that is exactly what Nevada does. The 55-year-old was convicted of attempted lewdness with a minor and became eligible for release in December 2013. The parole board heard his case Feb. 2, 2014, and granted him parole.

First Carter tried to get released to his girlfriend’s house, he said, but didn’t hear anything back from parole and probation. Next he picked a halfway house, but the parole division wouldn’t approve that one. He looked at a list of approved halfway houses but didn’t have money to stay at those, he said.

Then, Carter said, he wrote the prison chaplain asking how he could get money for a halfway house. He was told there wasn’t any.

Eventually, his sentence just ran out. He was released Oct. 29.

WHOSE BEST INTEREST?

The impetus for a plan to get out should rest with the parole board, not inmates, Horn said.

“If they put the responsibility on the prisoner the state is really putting its interests in the hands of this guy.”

Three members of an advisory committee on Nevada’s prison and parole systems called the backlog a bureaucratic error. The 17-member Advisory Commission on the Administration of Justice is appointed by the governor, lawmakers, judges and other officials, per state law.

Parole and probation officers are underfunded and overworked, committee members said. Problems processing parole releases, they said, should be fixed with a little help from prison officials and a big assist from state legislators.

“As I recall, the issue had mostly to do with people not having satisfactory release plans, which are inherently very difficult to do,” said Richard Siegel, a political scientist and longtime committee member.

Siegel said parole officers should work more closely with prisoners and start planning earlier.

Nevada Supreme Court Justice James Hardesty, another committee veteran, has fielded questions about the parolee bottleneck for the better part of a decade. He advised legislators to pony up more for parole officers before spending another penny to keep releasable prisoners in jail.

“The limitation on resources delays our release rate, which could be higher if we had facilities, jobs, treatment programs and other services necessary to assist parolees post-release,” Hardesty said. “It absolutely costs (Nevada) more, in the long run, to not to make these changes.”

Nevada spends an average of $54.15 per day to keep a prisoner in custody, according to the latest Department of Corrections figures.

State officials estimate supervising a parolee costs only $7.47 per day.

When asked about the backlog, state Sen. Tick Segerblom, D-Las Vegas and a member of the justice committee, said he doesn’t know what it might cost to fix the problem and predicted legislative action is unlikely.

“Until we have more money, I don’t see it happening,” he said.

“It’s amazing the amount of money we waste just because of people sitting around,” Segerblom said. “That’s Nevada for you — penny-wise and pound-foolish.”

YEAGER’S CASE REVIEWED

Russell Yeager, the inmate who stayed in prison 13 years after being granted parole, has spent the majority of his life in custody. He was sentenced in 1979 and paroled in 1995 to Massachusetts, to live with a woman with whom he was romantically involved. He was arrested in 1998 after he went to San Francisco without permission.

Yeager said inmates commonly get discouraged and give up on parole. He never stopped asking questions, he said, but he didn’t expect to actually be released.

In June 2012, the justice committee discussed Yeager’s case. Tony DeCorona, of Parole and Probation, gave a brief history of Yeager’s time in prison, saying he had been granted parole multiple times since 2001 only to be rejected by states where he wanted to move.

The parole board reviewed Yeager’s case again in 2009. Because he was so young when convicted, he fell under a new law granting mandatory parole to young offenders.

Yeager didn’t submit a plan but eventually asked to go to a halfway house, DeCorona said. Parole and Probation asked Yeager to submit a new plan, but he didn’t follow through.

In 2011, Yeager was accepted to a halfway house but didn’t qualify for indigent funding, so parole asked him to come up with a new plan, committee meeting minutes show.

Siegel asked if Yeager’s problem was systemic, according to the minutes.

DeCorona responded: “Yaeger’s (sic) case was not a lone case… (he) did not provide a viable plan and it had impacted him.”

Siegel said he asked about systemic problems because he wanted the commission to facilitate parole. But nothing changed for Yeager until 2014. It’s still unclear why.

‘PRISONERS DON’T WANT TO BE IN PRISON’

Latrisha Smith, 35, who was incarcerated at Florence McClure Women’s Correctional Facility in North Las Vegas on a low-level felony drug offense, described similar frustrations.

She was accepted at a halfway house, she wrote, but was denied indigent funding. She decided in March 2013 to just wait for her sentence to run out, but last August the parole division began working with her. She assumed the prison needed her bed for someone else.

Smith had no family or money, according to a list of inmates held past their release dates. She also failed to apply for help.

Parole Capt. Dwight Gover acknowledged the backlog but said his agency can do little to speed up inmate release plans.

For the 75 eligible inmates who didn’t bother filing a parole plan in October — typical in any given month, he said — there is even less that can be done.

The parole division releases around two in every three prisoners OK’d by the parole board, according to officials. Gover doubts those numbers will change anytime soon.

“The biggest reason people are past their eligibility dates has to do with non-viable (release) plans,” Gover said. “We have to exercise due diligence in investigating those plans, but there is nothing we can do about people that don’t want to get out.

Horn dismissed that argument.

“In 40 years experience, that has not been my experience,” he said. “Prisoners don’t want to be in prison, and it’s a mistake to think they do.”

Clark County Public Defender Phil Kohn agreed, saying inmates who don’t submit plans are likely so frustrated they just want to serve their time and be done with supervision of any kind.

Michael Meservey, 56, is one of the frustrated. Serving time for non-payment of child support, he was supposed to be released in October 2013 but opted not to work toward release.

Meservey’s release plan was rejected in April, according to parole board records. A board employee tried to reverse the rejection, advising Meservey to include the address of his home to show he had a place to go.

But Meservey told the Review-Journal he had already given Parole and Probation on multiple occasions the location of the trailer where he would live and was fed up with it.

“You get to the point where you’re just drained,” he said in a letter to the Review-Journal when he had less than five months left to serve. “I don’t even want their stinkin’ parole.”

When first asked about the backlog, Kohn said he wasn’t aware of it. But after checking he found his office gets five to 10 inmates a month asking for help with parole.

“For us they are former clients and there is nothing we can do. It’s more of a civil matter, and we’re not allowed to handle civil cases,” Kohn said. “There is nothing we can do about it. I’m hoping the ACLU will.”

American Civil Liberties Union of Nevada Director Tod Story said his group would like to fix what he sees as a broken system.

A legal challenge is a last resort, Story said, but would be considered.

Those lawyers won’t have an easy argument to make: The parole process by law is exempt from constitutional challenges.

Yeager, acting as his own lawyer, was stymied when he took the issue to the Nevada Supreme Court in 2004. He had yet to be denied indigent funding, so his poverty was not an issue for the court, which rejected his complaints about release plan rejections.

“Parole is an act of grace by the State,” the Supreme Court wrote. “As such, a prisoner has no right to parole. Yeager’s grant of parole was conditioned on the subsequent approval of a parole release plan, but no parole release plan was approved. No protected liberty interest was encroached upon … the parole board was not required to conform to the dictates of due process in reversing its original decision.”

Parole may be a privilege, Kohn said, but once granted an inmate should be entitled to a fair process under state law.

Since it’s not, Kohn and Story said, constitutional questions about equal protection and due process will arise.

A broken parole system actually undercuts the one thing prison is supposed to teach people, Kohn said.

“We want to teach them cause and effect. Reward and punishment,” he said. “All the lessons we want them to learn in prison that they didn’t learn as a kid are negated by us not rewarding someone who does behave.”

Russell Yeager considers himself reformed, even if it didn’t happen the way Kohn said it should. Yeager is now employed at the halfway house where he lives.

His takeaway after submitting dozens of release plans for years and then one day being released for seemingly no reason?

People rehabilitate in spite of prison, Yeager said, not because of it.