NTSB: Air traffic control routed plane toward mountains before deadly crash

A 2019 plane crash that killed three people on Gass Peak north of Las Vegas was caused by a pilot’s failure to maintain clearance from terrain, with federal investigators noting the pilot was following a route toward the mountains given to him by air traffic controllers at Nellis Air Force Base.

Killed in the Nov. 26 crash were pilot Gregory Akers, 60, of Henderson, Akers’ wife, Valeriya Slyzko, 48, and his mother-in-law, Nina Morovova, 71.

A final report on the crash from the National Transportation Safety Board indicates Akers, a retired air traffic controller, was piloting a Cirrus SR22 when the plane crashed into Gass Peak at an elevation of 6,500 feet. The safety board said the cause of the crash was Akers’ failure to keep the plane at a proper elevation to avoid the mountain.

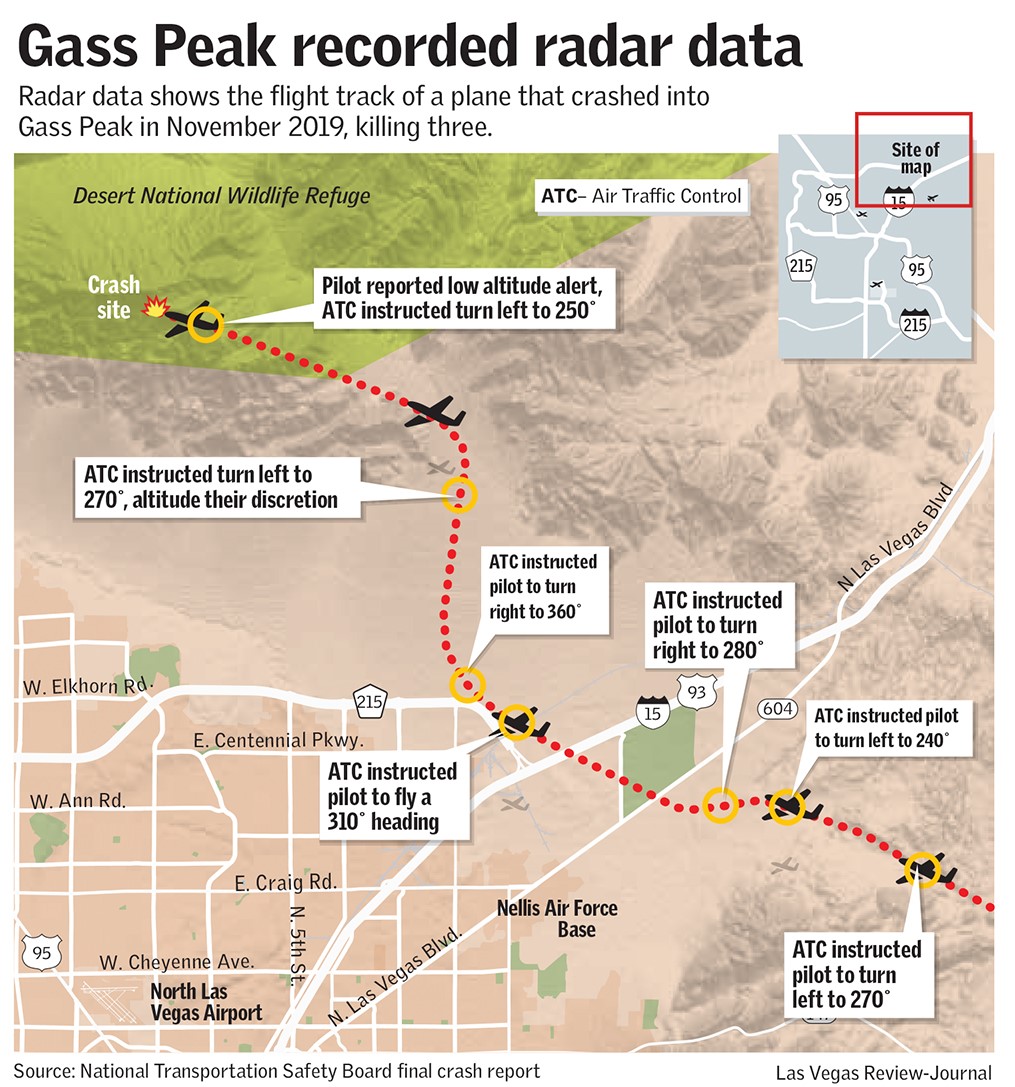

The report also documents how Nellis Air Force Base air traffic control put Akers on a path to an area of mountainous terrain about 15 miles north of Las Vegas as controllers simultaneously managed the flight paths of four F-35s and then four F-22s at the base.

The safety board report does not assign blame for the crash to Nellis air traffic control for routing the plane the way that it did, but one local pilot believes the air traffic control directives received by Akers did, in fact, play a role in the crash.

“I think they should have given him a caution saying, ‘Listen, you are in a potentially dangerous situation,’ ” local pilot David Brough said Monday.

Brough, a longtime bush pilot in Canada who now lives in Las Vegas and advocates for aviation safety, said he also noticed stark parallels between the 2019 crash and another fatal airplane crash at Gass Peak in 1999 that killed a cargo pilot.

“To me the recommendation should be to put a flashing light on top of the mountain,” Brough said. “I’m sure other people have had near misses as well … There is nothing like a light flashing in the windshield telling you you better be higher than that light.”

Aviation experience

Akers was a retired air traffic controller at both Harry Reid International and Dallas-Fort Worth International airports. He moved to the Las Vegas area from Dallas around 1996.

“He always had a love for aviation,” his cousin, Tina Lopez, said in an interview shortly after the crash. “He would fly small planes all around.”

Slyzko worked at the U.S. Postal Service processing office, 3755 E. Post Road. She was described by co-workers as a “great person” who was popular at work and who liked everybody.

The flight that day departed from Lake Havasu City, Arizona, with a destination of North Las Vegas Airport. Akers’ plane hit Gass Peak about 400 feet below the mountain’s summit, after dark, at 5:30 p.m. Akers was flying using visual flight rules. The safety board said he contacted the Nellis air traffic control at 5:20 p.m. to report his altitude of 6,500 feet.

“Throughout the following 7 minutes, the controller issued various heading changes to the pilot due to departing traffic at a nearby Air Force base, which the pilot acknowledged,” the safety board wrote in the report.

‘Altitude your discretion’

At 5:23 p.m., an air traffic controller instructed Akers to make a left turn “due to a departure of a flight of four F-35s” at Nellis, the agency’s report said. At 5:24, Akers was advised to turn left. At 5:25 p.m. Akers received a new heading, which Akers acknowledged.

“The controller then advised the pilot that a flight of four F-22s would be departing runway 21 and climbing to the north,” the report states.”The pilot responded that he was searching.”

There was more communication between the pilot and an air traffic controller as Akers received more directives. At times Akers referenced his plane’s tail number N7GA to identify himself. Then, at 5:27 p.m., Akers received a directive to head left, which Akers acknowledged.

“Five seconds later, the controller instructed the pilot ‘N7GA altitude your discretion,’ which the pilot responded with his call sign,” the report said.

At 5:29 p.m., the pilot stated, “we’re getting a low altitude alert for N7GA, we gotta turn left,” prompting the air traffic controller to tell Akers to turn left.

“No further communications from the pilot were received despite multiple attempts from the controller,” the safety board said.

A spokesman with the Federal Aviation Administration said this week the agency does not supervise air traffic controllers at Nellis.

Nellis spokesman Lt. Col. Bryon McGarry wrote in a statement emailed to the Las Vegas Review-Journal on Wednesday that any questions regarding the specifics of the crash should be directed to the safety board. Nellis air traffic controllers are FAA certified and adhere to the same standard of training and performance as all controllers throughout the National Airspace System, according to McGarry.

“Nellis AFB seamlessly coordinates with FAA controllers from Harry Reid Intl Airport, Las Vegas TRACON, Salt Lake Center, Los Angeles Center, and Oakland Center on flights into and out of Nellis AFB and flights that cross through Nellis airspace,” McGarry said.

Possible safety alert

The safety board’s report mapped out recorded radar data from the flight that shows a track headed in the general direction of the mountainous terrain prior to the crash. The report did not make any formal safety recommendations in its final crash report, although it did note FAA orders dictate that basic radar services provided to pilots flying under visual flight rules make safety alerts from air traffic controllers to pilots a top priority.

“Issue a safety alert to an aircraft if you are aware the aircraft is in a position/altitude that, in your judgment, places it in unsafe proximity to terrain,” the report said, citing FAA rules.

The agency also said other factors such as workload, traffic volume and the limitations of radar and time play a role in determining whether a traffic controller should issue a safety alert.

Brough said he believes a safety alert should have been issued. He also said Akers had a responsibility to know where he was in relation to the mountain.

“He knew where he was headed,” Brough said of the pilot. “It is a puzzler as to why he didn’t take action himself. You can deviate from a heading in an emergency situation.”

Brough said the crash is similar to a 1999 crash at Gass Peak in which a cargo plane slammed into the mountain, killing the pilot. The cause of the crash was the pilot’s failure to maintain separation from terrain while flying under visual flight rules at night.

“Contributing factors were the improper issuance of a suggested heading by air traffic control personnel, inadequate flight progress monitoring by radar departure control personnel, and failure of the radar controller to identify a hazardous condition and issue a safety alert,” the safety board said in a final report on the 1999 crash.

Contact Glenn Puit by email at gpuit@reviewjournal.com. Follow @GlennatRJ on Twitter.