On Pioneer Trail, a chance to show Las Vegas’ Historic Westside

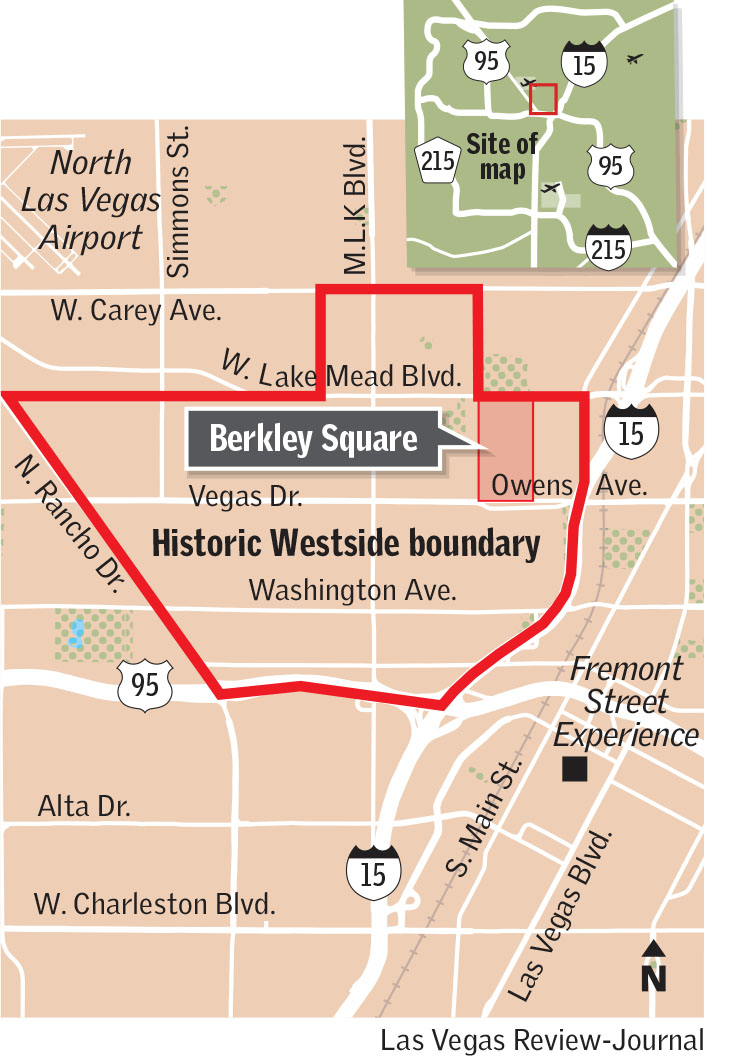

The Pioneer Trail, a 16-site route of historically significant locations in Las Vegas, starts at the Springs Preserve and snakes east until it reaches above the brim of downtown.

It’s a multi-agency project adopted in 2002 to underscore the rich, early beginnings of Las Vegas spanning the period of its earliest settlers to the 1950s — “a vision of the West Las Vegas community” to celebrate its culture and heritage, the trail’s brochure says.

Beyond the early produce farm and the Old Las Vegas Mormon Fort, the Woodlawn Cemetery and the Las Vegas Indian Colony, many of the Pioneer Trail’s points of interest sit squarely in the Historic Westside, the pulse of the city’s African-American community. It has struggled with economic development for decades.

“A lot of people, when they think of the black neighborhood, they think of degradation, stuff falling down, homeless people,” said Katherine Duncan, president of the Ward 5 Chamber of Commerce and also a resident of Historic Westside.

The Pioneer Trail, she said, is one available avenue by which to educate outsiders, not only on the city’s broader past but also on the neighborhood’s storied history to transform assumptions.

“There’s a lot to be proud about here,” Duncan said during a recent tour. “But if you don’t know what you’re looking at, then you can come and form all kinds of opinions.”

On a stretch of Jackson Avenue are vacant lots and tattered structures. But the thoroughfare was once the hub of the Historic Westside’s commercial district in the 1940s and 1950s. A row of nightclubs attracted elite entertainers including Sammy Davis Jr. and Nat King Cole.

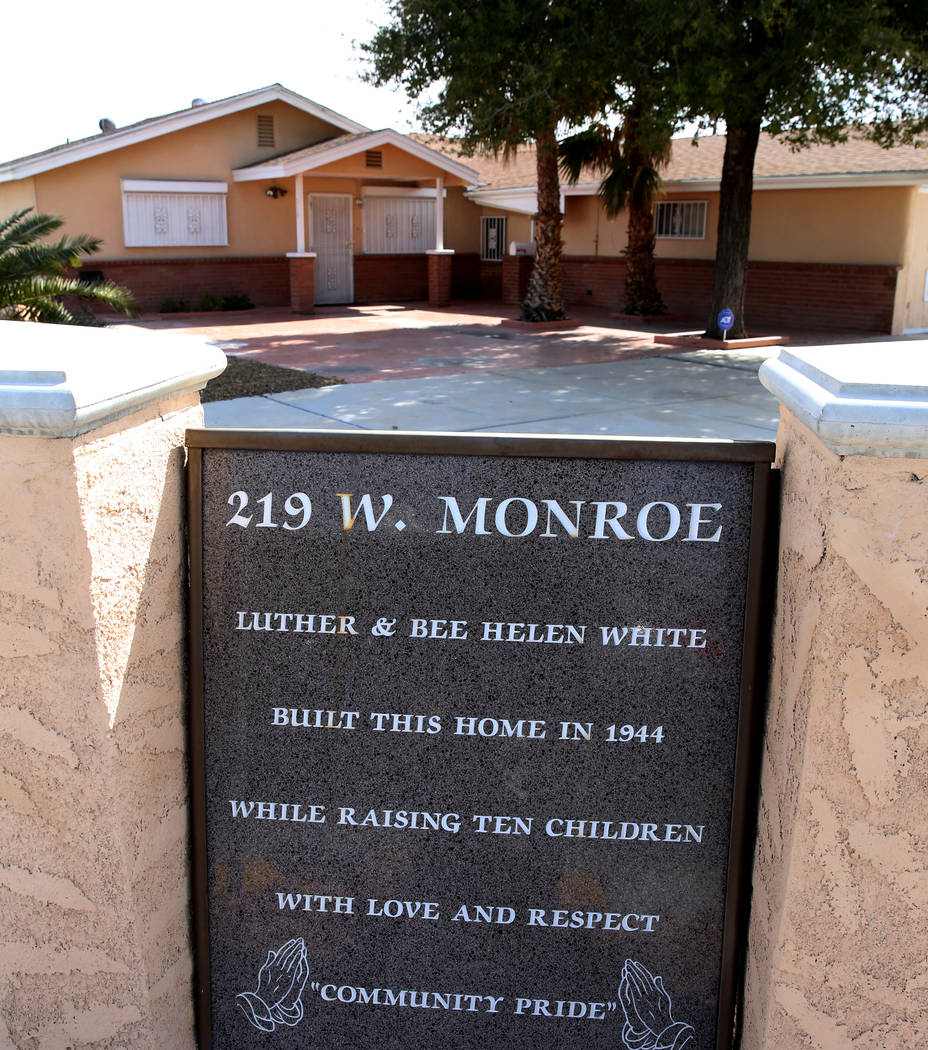

And few original buildings remain of the McWilliams Townsite, but the site, built in 1905, was the city’s first business and residential development.

While those sites require imagination, others are easily visible.

One is the still-vibrant St. James the Apostle Catholic Church, built in 1940 as Las Vegas’ second-ever Catholic church. The half-timbered Christensen House, which resembles a castle with a tower and rock facing, was built in 1935 by Lucretia Tanner Christensen Stevens, a black woman whose roots trace to pioneers.

The Moody House was the home where Herman Moody, the city’s first black career policeman, was raised. And the Westside School, which has undergone renovations in recent years, was the first grammar school in Historic Westside and now serves as home to community radio station KCEP.

Harrison’s Guest House, which today offers tours and also maintains a sustainability garden at its 1001 F St. location, acted as a short-stay residence in the 1940s and 1950s for black entertainers, such as Davis Jr., who were barred from renting rooms in the hotels on the Strip where they performed.

“We just want to show a balance,” Duncan said. “Our image has really been tainted because we’re always associated with negative, so I want people to see some positive.”

Looking out for one another

The neighborhood has been stricken for years with a stigma raised by belonging to a ZIP code with extreme rates of food insecurity and poverty. But residents in the Historic Westside say the reputation is perpetuated by those who live elsewhere.

“The people outside of here have bought into the idea that this is the lowest of the low,” said Abdul Shabazz, owner of a mobile denture lab business, who suggested the neighborhood had been hampered by a lack of positive information. “If this ZIP code is repackaged, it’d blow out the water.”

Ora Bland, 85, arrived before 1955 with her husband, who went to work for the government’s atomic testing program. She has resided in the same house ever since, which now is a short walk from the Interstate 15 underpass at F Street, where homeless congregate in the tunnel, a convenient resting spot located near social services.

Bland, however, said they mostly do not bother her. But if they did, she would have backup.

“In this particular neighborhood, right here,” she said, “everybody looks out for each other.”

Las Vegas Ward 5 Councilman Cedric Crear, who lives in the area’s Bonanza Village, said residents “have a level of pride” and, like others, he noted he intentionally chose to build a life there.

Continuing revitalization

The Pioneer Trail, he added, was merely one portion of an ongoing revitalization in the historic area that will include welcoming signs and also a marquee at the Westside School.

Duncan said the plan is to add street markings to indicate the map toward each site and to increase the number of sites. Particularly, Duncan eyed Berkley Square, a nationally recognized historical neighborhood constructed in 1955 as the first subdivision for blacks in the state.

It was designed by famed black architect Paul Revere Williams, and Duncan points to that neighborhood and others such as Bonanza Village as signs of plenty of desirable living in the Historic Westside.

There was a period, however, when Berkley Square was on the decline, according to Ruth D’Hondt, a longtime resident and former president of the now-defunct neighborhood association.

Powered by resident volunteers and a city partnership, Berkley Square turned around, she said. But D’Hondt, 77, worried that interest in historical significance — the same curiosity that Duncan believes can be a conduit to showcase the Historic Westside — might be waning in the neighborhood at large among new generations of families.

The neighborhood group she led from 2006 until two years ago is without a clear successor, and many involved either died or became too old to participate, she said, leaving her to suggest that “someone must carry (the torch), or it will die.”

For those like her, Duncan and others, lacking enthusiasm for the area’s past is an unfamiliar concept.

“Every city has a history,” Duncan said later in the tour. “Why don’t we tell ours?”

Contact Shea Johnson at sjohnson@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0272. Follow @Shea_LVRJ on Twitter.

Pioneer Trail

For tourists and locals interested in scheduling a tour of the Pioneer Trail, call Harrison House at 702-850-0249 or Katherine Duncan at 702-490-2699 or email info@harrisonhouselv.org.

Bicyclists may visit bikethepioneertrail.com for more information.

The trail, which has signs directing the tour posted throughout the city, is funded by the Southern Nevada Public Lands Management Act and created in conjunction with the city of Las Vegas, Clark County and Preserve America.