Social distancing proves challenging on Las Vegas-area buses

It’s just after midnight on a Saturday, and a woman tosses a freshly used tissue onto the floor of the bus. A man to her right stands up from his seat and, with his foot, nudges the tissue down the aisle, out the back door of the 113-North.

He sits back down, directly next to the woman, in a seat marked with a message from the Regional Transportation Commission not to sit next to other passengers, and the bus doors close.

Thousands of people are still riding buses in the Las Vegas Valley. People who cannot work from home and essential employees such as nurses and grocery store clerks, as well as many homeless people, still rely on them to move around.

While no public health officials have linked any COVID-19 cases to RTC bus passengers, the agency has reported that two drivers have tested positive for the disease.

Some passengers fear they will or already have contracted the virus from another passenger, but others aren’t at all worried about that, instead looking out for their physical safety at bus stops as people grow more desperate in the face of massive job cuts.

“Wait until people are running out of money and they ain’t got nothing to eat,” said Ricky St. Patrick, who was waiting for the 105-North one evening in early April.

He said he watches his back a little closer in between bus stops and thinks about how the pandemic is making things worse for people who already are struggling.

St. Patrick, a 29-year-old who took the bus before the health crisis, said the economic shutdown on the street level was “putting people in a position that they’re backed into a corner, and that’s very dangerous.”

Though Nevada Gov. Steve Sisolak ordered thousands of businesses and agencies closed in mid-March to mitigate the spread of the coronavirus, he did not order buses to stop rolling.

Generally, the routes with some of the highest rider counts before the shutdown remain the busiest. According to a Las Vegas Review-Journal analysis of ridership data, the routes that still had more than half of their passengers at the end of March also serve some of the poorer areas in the Las Vegas Valley. No ridership data for April was available.

One of those routes, the 113, which runs from downtown Las Vegas to Nellis Air Force Base and back, remains one of the RTC’s most populated, serving the COVID-19 shelter at Cashman Center, essential grocery and convenience stores, restaurants serving takeout and auto shops still tuning up cars, with thousands of houses and apartments.

Encouraging social distancing

Renee Smith, 38, said one day she saw the driver on the 113 skip three straight stops where people were trying to get on.

Transportation officials say that’s on purpose. Drivers may offload passengers, but not pick up new ones, when a bus is reaching capacity. Drivers will flip on the vehicle’s “NOT IN SERVICE” sign at the front of the bus and keep driving.

RTC Deputy CEO Francis Julien said in an interview Tuesday that the commission and its contractors have worked to keep enough buses and drivers available ahead of time on the busiest routes so buses don’t fill up. It’s part of an effort to promote social distancing.

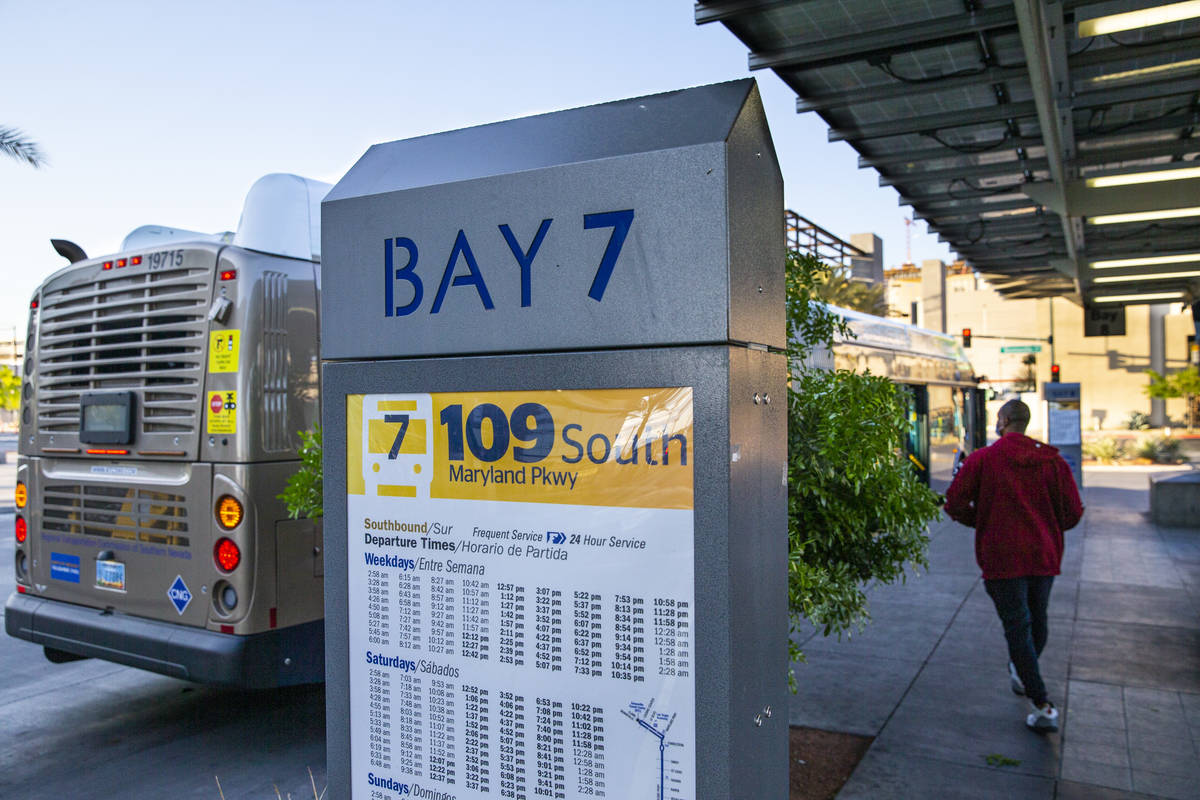

Jacob Simmons, the commission’s principal transit operations planner, said the busiest routes through the pandemic are the 109, 113, 202, 206 and the Boulder Highway Express. Those were among the most-used routes before the shutdown.

“Folks still have to go out to the grocery store occasionally. You still have to get to work for essential jobs,” Simmons said. “So it stands to reason that the places where that was happening the most before are places where that’s happening (now).”

But what was the busiest route overall, the Deuce, featuring a double-decker bus that runs up and down the Strip, has seen its ridership fall well beneath the levels on all five of the busiest routes, respectively, according to the Review-Journal’s analysis.

Smith said she has noticed the bus drivers’ efforts to give people enough space from one another, including the social distancing signs on some seats. She said she and her partner, who accompanied her downtown, still sit close.

“We’re like, well, we’ll probably give it to each other anyway,” she said of the virus.

Southern Nevada Health District spokeswoman Jennifer Sizemore said the agency is not aware of any COVID-19 cases involving people who have used public transit.

The American Public Transportation Association advises passengers and riders not to use the bus or other modes of public transportation during the pandemic unless it is necessary for visits to other essential services such as hospitals and stores.

“Riding the bus has the same inherent issues as walking the aisles of a grocery store or pharmacy,” the association said in a statement.

A little before 1:30 a.m. on Easter Sunday, a 60-year-old woman who said her preferred name was Ms. Opaneye, which she said was her married name, “but you can call me whatever you want,” walked onto the 113 from the Washington Avenue stop on Las Vegas Boulevard North as the bus made its way back toward the Bonneville Transit Center.

Black and homeless, Opaneye is among the population that officials and advocates have warned is being affected more severely by the virus.

In Clark County, data has shown that black people have been infected with and have died from COVID-19 at a disproportionate rate.

Though they make up about 11 percent of the population in Las Vegas, black people represent about 37 percent of the RTC bus riders, according to the latest data from the commission.

Opaneye said riding buses during the night gives her a better chance of following her self-isolation orders than sleeping at homeless shelters.

With the Regional Transportation Commission directing people to board only from the back doors of buses, there is no practical way for drivers to accept payments from cash-only customers without coming into close contact with them, which means passengers have been riding for free.

‘People gotta go places’

Advocates and public officials have said that homeless people, because of their circumstances, will bear the brunt of the pandemic. Clark County and Las Vegas on Monday opened an $8 million quarantine shelter at Cashman Center.

But before that opened, Opaneye was in and out of her preferred emergency room because she had what she said felt like pneumonia. On April 8, she walked off the 109-South, the bus that runs up and down Maryland Parkway.

That night, she laughed and apologized for laughing as she explained at the South Strip Transfer Terminal how she did not know what else to do.

“I’m 60. It’s supposed to rain tonight,” Opaneye said, at times touching the front of her worn surgical mask. “This is better than being out in the rain.”

Her only plan that night, she said, was to go back to the emergency room to try to find out her results. She said she had been screened for COVID-19.

On Easter Sunday, when she got off the 113 in downtown Las Vegas, she said she learned that her results were negative.

“But that’s based on when I was tested,” she said.

She has spent many more days riding along with thousands of passengers on routes such as the 113 and the 109, two of the routes that have remained popular.

A Review-Journal analysis of census data showed that these routes are serving primarily black and Hispanic neighborhoods. These routes also serve poorer areas in the valley, according to the data.

The U.S. surgeon general has warned that the coronavirus will affect people of color more severely because of some socioeconomic and health factors that existed before the pandemic.

In a 2016 study, the Pew Research Center determined that black and Hispanic people in metro areas are especially likely to need public transportation because of factors that include being less likely than white people to own a vehicle and being more likely to live farther away from their workplaces than white people.

For frequent 109 passengers like Fabian Rosas, 23, taking the bus between work and home is his only option right now, as it was when he hopped on a Greyhound bus from Irving, Texas, and moved to Las Vegas just weeks before everything went dark.

“There’s only so much you can do,” Rosas said at the Southern Strip Transfer Terminal the night of April 4. “People gotta go places.”

Contact Dalton LaFerney at dlaferney@reviewjournal.com or at 702-383-0288. Follow @daltonlaferney on Twitter.