Take a tour of a quaint Cold War relic, the bunker

At the chilly depths of the Cold War, the survival of Southern Nevada hinged on a hole in the ground in the southwest valley.

There, in a bunker made from buried railroad ties, a hand-picked crew of local officials planned to ride out the fallout, then emerge to restore order to post-apocalypse Las Vegas.

“If the bomb came, this was where you were going to be. This is where they planned to hole up,” said Mark Hall-Patton, museums administrator for Clark County.

Today, the valley’s command and control shelter sits locked and largely forgotten under the dirt parking lot of the county’s Arden maintenance shop, near Rainbow Boulevard and Blue Diamond Road.

The shelter is still used to store some surveying equipment, but it’s rare that anyone ventures inside, said Rich Schnackenberg , a county park maintenance supervisor and keeper of the bunker key.

With Schnackenberg’s help, Hall-Patton recently opened the underground relic and flipped on the lights for a tour by the Review-Journal.

Had the Soviet Union ever unleashed the “big one” on Las Vegas, those who managed to get to the bunker were instructed to strip down and wash off radioactive fallout in a shower at the bottom of the wooden steps.

On a wall nearby is a cabinet that once held coveralls for apres-shower wear.

Hall-Patton said the facility was equipped for 27 men and nine women — just don’t ask him to explain why or to defend the obvious gender inequity.

He also can’t say for certain who was on the invite list, but the shelter likely would have housed the sheriff, the mayors of Las Vegas, Henderson and North Las Vegas and key administrators from the cities and the county.

“They would have been trying to help people, trying to get through the emergency,” Hall-Patton said.

The bunker, about 6 feet underground, was to serve as the control center for dozens of other fallout shelters in the valley — sort of a local government in exile.

Hall-Patton said it probably was built where it was — then the tiny community of Arden on the outskirts of town — because it seemed like a safe distance from likely targets such as Nellis Air Force Base, downtown Las Vegas and Hoover Dam.

“It was very much on the edge,” he said. “They were planning, just in case.”

The bunker had a kitchen and a small infirmary, and it was stocked with enough food and water for several weeks or months.

Most of the space is taken up by a central control room and smaller offices once filled with communications gear, instruction manuals and emergency plans.

The men and women were to have separate sleeping quarters, each packed tight with narrow, triple-deck bunk beds that are still there today.

At each end of the bunker, staircases lead back to the surface.

“When you look at what was down here, this wasn’t built for enjoyment,” Hall-Patton said. “If you like summer camp, this might have been all right.”

The mound of dirt and rocks covering the bunker is still topped with a communications tower, a generator and a row of ventilation pipes covered with metal cones meant to keep radioactive dust and ash from blowing inside.

It all seems a little quaint to Hall-Patton, who said, “I’m not sure how well they would have survived. Not sure that’s where I would have wanted to be, but that’s what we had.”

A COLD WAR TROVE

Hall-Patton had visited the bunker before, most notably in the late 1990s, when he helped remove some of its more interesting items for preservation and display at the Clark County Museum.

It’s hard to say exactly when the bunker fell out of use, because it was never really used. Hall-Patton said it appears officials stopped conducting drills there in the late 1970s.

“They had stopped using it, but everything was still down there,” he said.

Plenty of Cold War artifacts remain, including several huge maps “from when there was barely anything on the map,” Schnackenberg said.

One of the maps identifies UNLV by its pre-1969 name, Southern Nevada University, and includes such long-gone places as the Dunes, the Sands, Castaways and the Thunderbird.

Where the map refers to “The Strip,” it includes the motto “Show Place of the Nation,” perhaps to remind the survivors what all that melted neon was for.

Other maps, since removed for posterity, showed potential fallout patterns from various strikes.

“Las Vegas had the test site, it had Nellis, so it was probably on some list someplace,” Hall-Patton said. “Back then, pretty much everybody thought they were on the (Soviets’) list.”

Other artifacts gathering dust in the shelter include a trash can and a 2-foot-tall, stand-alone ashtray, each emblazoned with the red, white and blue Civil Defense logo.

On a desk in the communications room is yellowed piece of paper with a typewritten guide to how much time you should spend outside at various radiation levels.

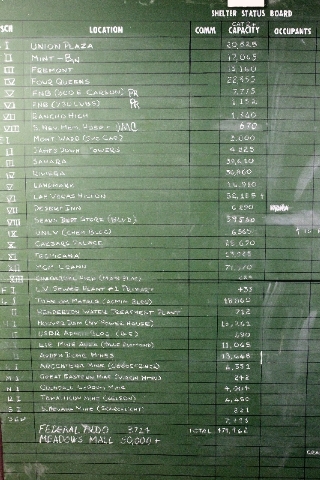

A wall-sized chalkboard in the control room still bears a 40-year-old list of more than 30 fallout shelters, many in places that no longer exist.

For each shelter, two different capacities are listed, depending on the severity of the attack.

A “Category 2+” strike would leave shelter for nearly 500,000 people, with the largest concentration of 71,570 expected as long-term guests at the original, 2,000-room MGM Grand.

Pity the 433 souls who might have found shelter in Las Vegas Sewer Plant No. 1.

Hall-Patton said many of the resort properties doubled as shelters because they were some of the most robust buildings in the valley, and that’s generally where the people were.

“They didn’t want anyone to be away from the casinos, of course,” he said with a laugh.

DUCK AND COVER

The bunker was built in the early 1950s, at a time when survival supplies were being tucked away all over the place. Those places included the old underpasses on Charleston Boulevard and Tropicana Avenue and in mine shafts throughout the region.

“It was something that ran through everything,” said Allan Palmer, the executive director and CEO of the National Atomic Testing Museum in Las Vegas.

Those were the days of “duck and cover,” when a cartoon turtle in an army helmet taught American children to dive under their school desks the moment a nuclear flash lit the sky.

By 1963, fallout shelter space had been identified for 104 million Americans, with enough public shelters marked to accommodate some 46 million people, according to Federal Emergency Management Agency documents.

Palmer said the nationwide push to build large civilian bomb shelters and stockpile rations began to taper off in the late 1960s and early 1970s, as federal funding for such efforts fell off.

The reasons are difficult to pinpoint, though resignation may have had something to do with it.

By then, Palmer said, “people were getting a little more sophisticated” about nuclear weapons and the grim realities that would face those who survived an all-out war.

Even at the time, some academics argued that the sheltering craze might actually be dangerous. They suggested that the more people convinced themselves they could live through a nuclear war, the more likely such a war became.

As it turned out, 1963 was the peak of nuclear preparedness in the United States.

The decline of the bomb shelter was sown that year with the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, a major advocate of Civil Defense, and a treaty that put a stop to above-ground nuclear testing by the two superpowers.

“There weren’t mushroom clouds popping up all over the world,” Palmer said, so perhaps the threat seemed more remote.

There are no plans to do anything with the county’s old command and control bunker, where the biggest hazards these days are spiders, claustrophobia and rodent-borne diseases.

Hall-Patton said the shelter survives only because “it would have taken a lot more effort to dig it out and fill in the hole.”

Conceivably, it could still be used in an emergency. By someone, anyway.

“I’m the only with the key, so I’m going to run in and lock the door behind me,” Schnackenberg joked. “All the rest of you can burn in the nuclear holocaust.”

Contact reporter Henry Brean at hbrean@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0350.