When Las Vegas’ Westside boiled over after Rodney King verdicts in 1992

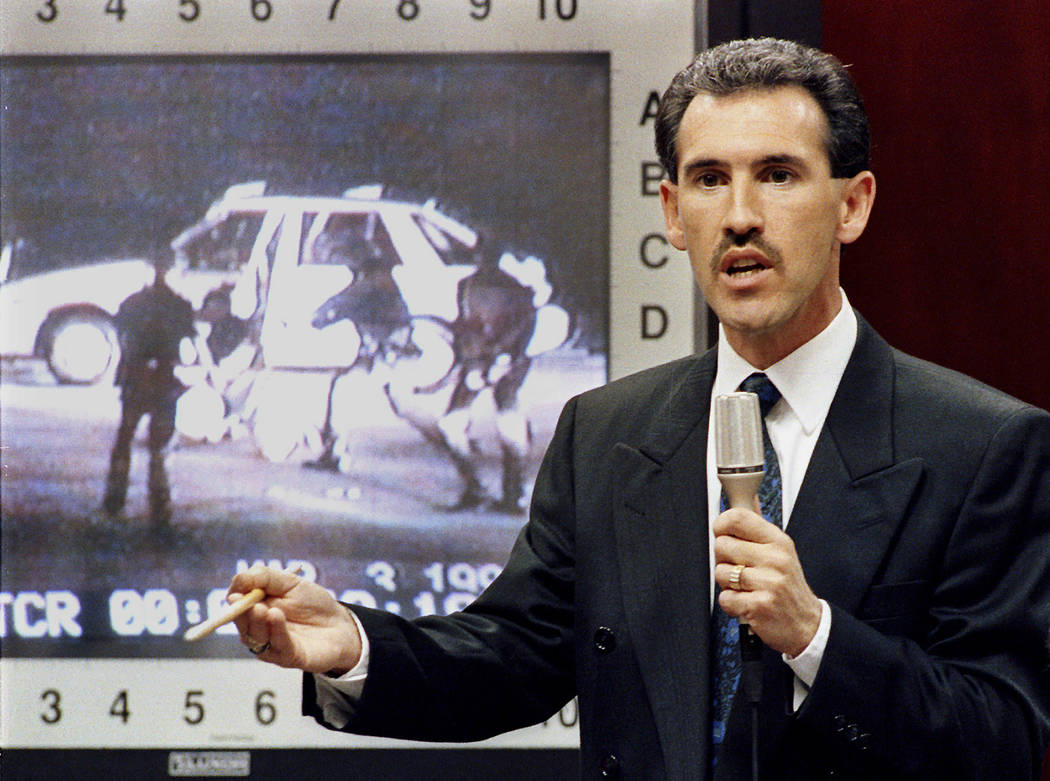

Four white police officers, one black motorist and two words — “not guilty” — read aloud 10 times in a quiet Los Angeles courtroom 25 years ago.

It was 3:15 p.m. on a Wednesday. The moment had been building for 14 months, since witness footage first aired on a Los Angeles news station showing police officers beating Rodney King after a high-speed chase, igniting a national conversation on police treatment of minorities.

The verdict, celebrated by the officers in the courtroom, unleashed outrage in Los Angeles that turned into riots, looting, fires and shootings. The unrest would roll on for days as separate, volatile protests sprouted in other cities.

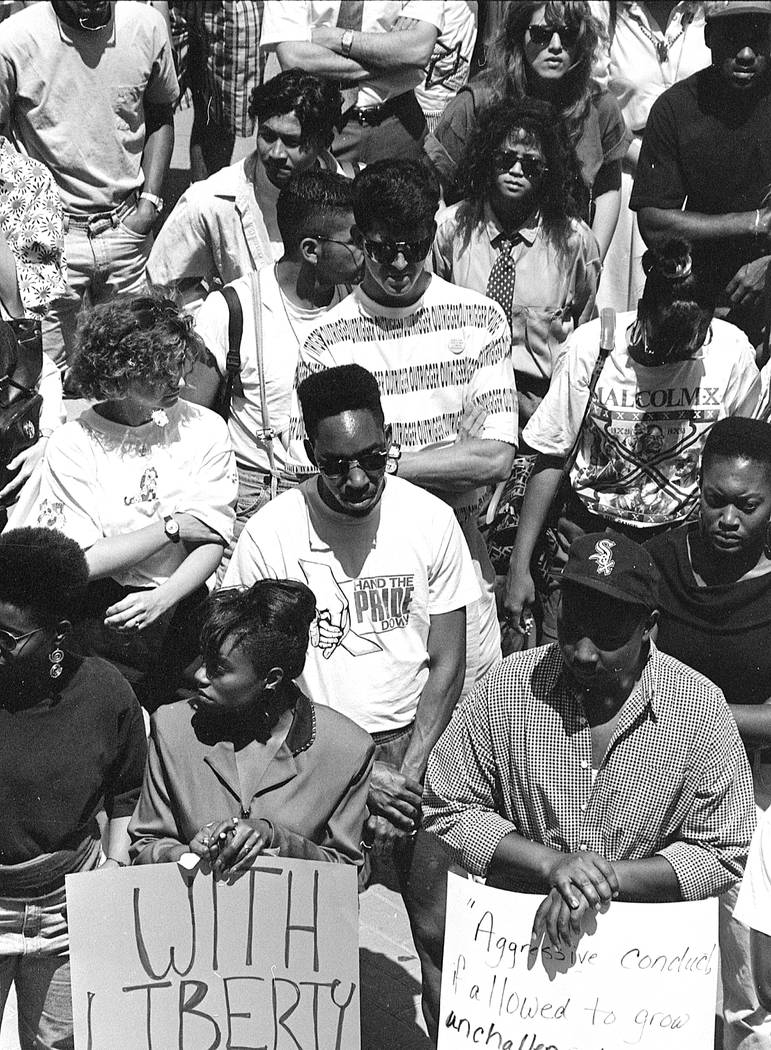

In Las Vegas, the day after the verdict, protesters peacefully marched from the Historic Westside, then a predominantly black community, to downtown, hoping to air their frustrations on Fremont Street. Before they made it, officers ordered the protesters to turn around.

It’s unclear if that caused what happened next. But late in the afternoon, a riot broke out in the Westside, an eruption so quick and immense that local police and fire crews eventually refused to respond to calls for service, leaving many in the area to fend for themselves.

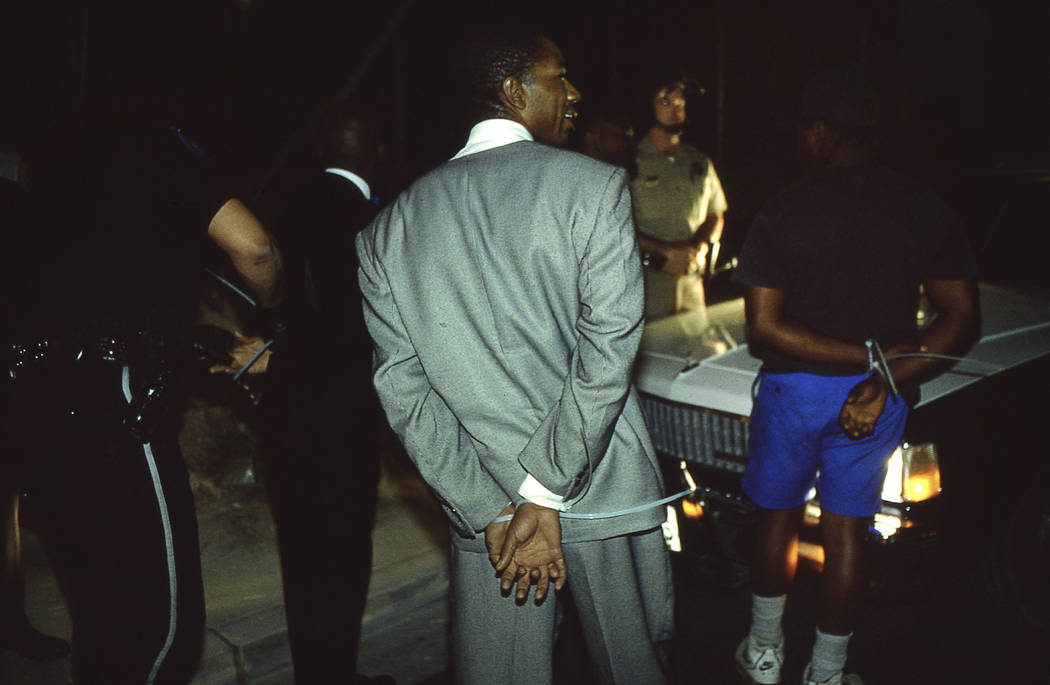

One person died, 37 were injured, and 111 were arrested during what became a pivotal moment in police and community relations.

Wednesday, April 29, 1992:

While residents privately absorbed the King verdict, streets throughout the Las Vegas Valley were quiet. Las Vegas police spokesman Lt. Charles Davidaitis told the Las Vegas Review-Journal he was aware there may be a local response to the verdicts, but police didn’t expect unrest.

“We merely suggested that (patrol officers) be just more sensitive to the issues and concerns that people have out on the street,” he said.

North Las Vegas police Chief Ron Lusch told the newspaper: “We realize that we have been put under the microscope of the public, and it’s going to be a while before all police departments across the country regain trust.”

Thursday, April 30:

After protesters were turned back from Fremont Street, unrest quickly spiraled into the Westside riots.

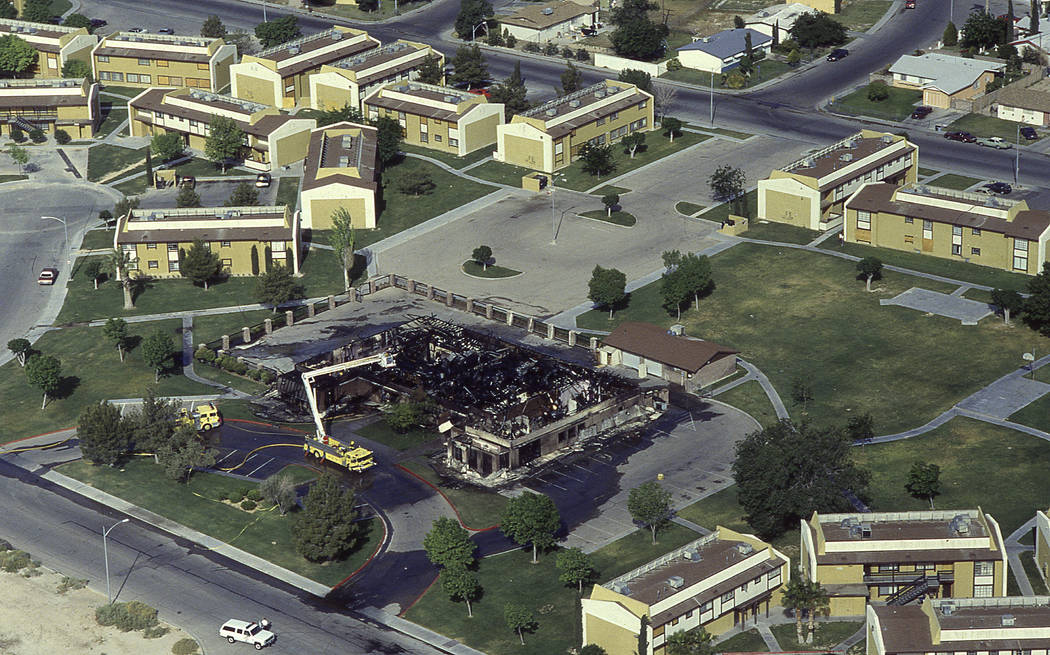

The worst damage occurred at Nucleus Plaza, home to the Nevada offices of the NAACP and numerous businesses. Looters smashed windows, ransacked stores and threw Molotov cocktails, destroying the strip mall near Martin Luther King Boulevard and Owens Avenue.

Two police substations in Westside apartment complexes also were torched, along with a gas station at Martin Luther King and Alta boulevards, south of the historic district’s borders.

Fire crews and ambulances were escorted by police into riot-torn areas but at times retreated because of gunfire. No firefighters were hurt, but one engine was pierced by a bullet.

At least 90 blazes were set – 40 in buildings and the remainder car and trash can fires, officials said.

An officer was shot in the arm about 9 p.m. Four police cars also were struck by gunfire.

At least two dozen people were injured in the unrest, which spread to parts of North Las Vegas. One was Joe Penrod, a white Economic Opportunity Board driver who was attacked by several black men while taking clients home from Opportunity Village.

Two people were shot and killed, but their deaths were later determined to be unrelated to the riots.

Las Vegas Mayor Jan Jones declared an emergency and instituted a 10:30 p.m. curfew in the Westside, meaning no one could enter or leave. Borders with downtown were cordoned off, and officers drew their weapons on anyone who came too close to roadblocks.

Las Vegas City Hall also was closed “to protect employees and the facilities,” City Manager Bill Noonan said.

Gov. Bob Miller mobilized about 400 Nevada National Guard troops after Clark County Sheriff John Moran requested assistance, but they were not deployed.

Miller, a former police officer and district attorney, was in New Orleans when he received word of the riots. He canceled scheduled appearances and flew to Las Vegas. “I can understand that there’s frustration, but violence is a totally inappropriate response and won’t be condoned in Nevada in any way, shape or form,” he said.

The UNLV Black Students Association organized a peaceful protest on campus. At least 200 students attended.

Planes could not land at Los Angeles International Airport because smoke billowing from the riots below was too thick, so many flights were diverted to Las Vegas, including one carrying the Rev. Jesse Jackson.

Amid the verdict outrage, the Nevada chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union renewed a request for the U.S. Department of Justice to bring a civil rights case against Las Vegas police for the death of casino floorman Charles Bush. (Bush died July 31, 1990, during a struggle with three Metropolitan Police Department officers who entered his apartment without a search warrant. After a wrongful death case was settled in 1993, Metro paid Bush’s family $1.1 million).

Friday, May 1:

Friday, May 1:

Skeletal remains were found early Friday in the ruins of a Nucleus Plaza grocery, officially the sole riot-related death. “More than likely, it was a looter,” Metro homicide Sgt. Parker McManus said.

The remains later were identified as those of Rancho High School student Isaiah Charles Jr., 18. His death was ruled an arson-homicide, since the building was intentionally set ablaze. Family and friends told the Review-Journal that Isaiah was a good student and active in ROTC. “I don’t think he was part of a riot. I believe he might have been trying to help someone,” said Tiffany Charles, Isaiah’s 17-year-old sister. “I just don’t think he was that whacked to go into a burning building otherwise.”

Sixteen schools in the Westside and North Las Vegas were closed, and extracurricular activities were canceled, angering many residents. The Clark County School District refused to allow buses to enter the Westside to pick up students who usually were bused to different schools. “I have a problem when you deprive our kids of a basic education,” one parent said at a City Council meeting that day. All other valley schools remained open.

Many services in the area were shut down. Garbage piled up. Food in refrigerators spoiled as 3,000 waited for Nevada Power Co. to restore electricity.

Government offices serving approximately 29,000 people were closed. Mail delivery was canceled, so hundreds lined up at the only Westside post office. “I don’t understand how they can do this to us,” one woman said. “We are people, too. It’s like we have to be herded around like we are a bunch of animals.”

Two teens who had looted a North Las Vegas convenience store the previous night came back and returned money stolen from the registers. “They told me it wasn’t about the robbery, it was about Rodney King,” the store’s owner, Henry Clark, told the Review-Journal. “I couldn’t believe it.”

Gun sales around the valley soared. “People just want to protect themselves. I guess they’re probably not sure what’s going to happen,” gun store manager Dwight Griebel said.

Community radio station KCEP switched from music to a talk format for about four hours, letting callers voice their frustrations on air. Some were supportive of the riots; others weren’t. Almost all said they were personally affected by the King acquittals.

A morning meeting of the Las Vegas City Council became heated, as Mayor Jones proposed extending the Westside curfew through Saturday.

“You cannot talk about imposing a curfew on a community who have nowhere else to go,” said then-state Assemblyman Wendell Williams, whose district included the Westside. He also argued that if police treated Westside businesses like downtown businesses, much of the destruction could have been avoided. “It’s law enforcement in some communities and service in another community,” he said.

The mayor defended the curfew and law enforcement’s actions: “In this situation, we wanted to preclude any larger degree of violence on the community at large,” she said.

At the end of the meeting, a voluntary, citywide 7 p.m.-to-7 a.m. curfew was instituted for Friday and Saturday.

Saturday, May 2:

Many Westside businesses reopened, and weary residents tried to return to a sense of normalcy. U.S. Sen. Harry Reid visited the Westside, touring damaged buildings and businesses and speaking with residents.

About 60 people marched from the Westside to City Hall, protesting peacefully while weaving through tourists on Fremont Street.

“This is our way of expressing that this is not an isolated incident, that it’s the norm rather than the aberration of the norm,” one of the protesters, Reggie Stewart, told the Review-Journal. “Police use a double standard when dealing with black people. They enter our neighborhood with guns drawn and a combative attitude rather than trying to understand. Rodney King is an everyday thing.”

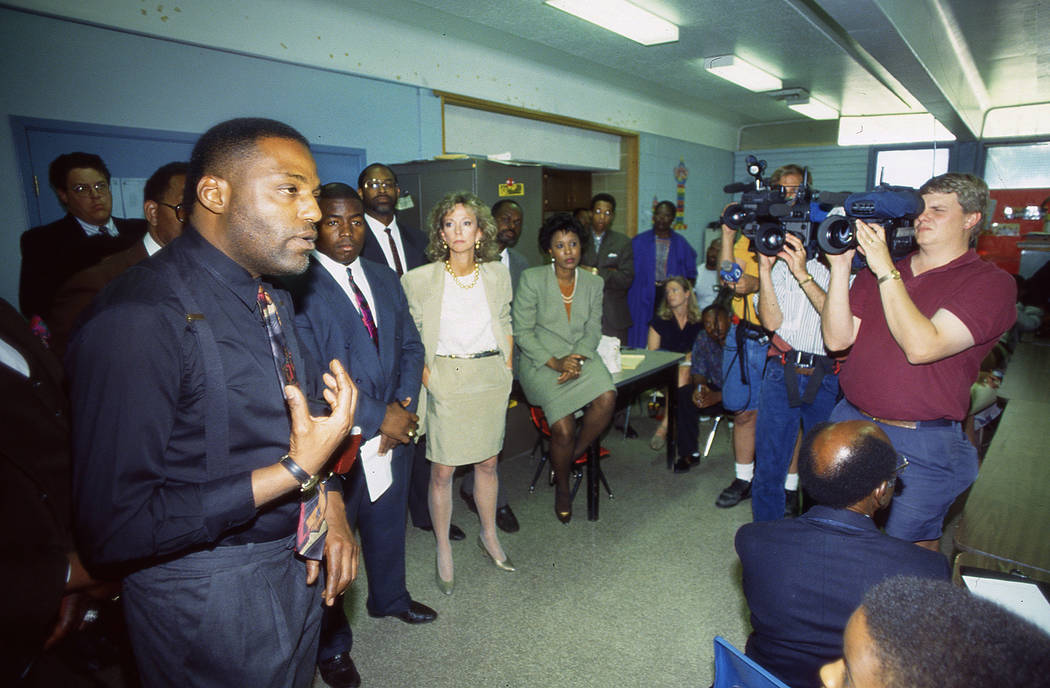

The City Council held another two-hour meeting that included the governor, the mayor and several other community and state leaders. They emerged with a pledge to help the Westside rebuild. “I think it went very well,” said state Sen. Joe Neal, D-North Las Vegas. “We were able to get together and work on long-term solutions.”

Sunday, May 3:

Gov. Miller attended a service at Second Baptist Church in the Westside. Churchgoers listened as he and the Rev. Willie Davis discussed the acquittals, the ongoing riots in Los Angeles and the destruction many had witnessed at home. “Violence isn’t the answer. Active participation in the democratic process is what’s needed to change the system,” Miller said.

At UNLV, the Thomas & Mack Center hosted the NBA playoff game between the Los Angeles Lakers and the Portland Trail Blazers, which was moved to Las Vegas as a precaution due to the rioting in Los Angeles. Several Las Vegas police officers entered the arena wearing helmets and shields, their nightsticks drawn. The Lakers lost, and no incidents were reported at the game.

Monday, May 4:

Monday, May 4:

The Las Vegas Fire Department estimated $6 million in damage from Thursday’s rioting and looting. Debris cleanup would begin after fire investigations were finished, officials said.

Bus service resumed and schools reopened. Many classes discussed the verdicts and unrest in an effort to understand why it happened and what it meant moving forward.

Tuesday, May 5:

Police returned to normal shifts after working 12-hour days with all time off canceled.

Black leaders began to criticize police and fire crews for not responding during the riots. In response, Lt. Davidaitis, the Metro spokesman, said, “We couldn’t fulfill our obligations because we were under siege.”

Leaders also questioned why the first protesters were turned away from downtown.

“Our intelligence was that if that group had reached downtown, they were ready to set fire to the hotels,” Metro Lt. Steve Franks said. “Had it not been for our officers, this town would have gone up in flames. These so-called leaders didn’t have the guts to be out there then, and now they’re shooting their mouths off against our officers. I find it repugnant. Our people did an absolutely magnificent job.”

Sen. Neal retorted: “I didn’t see or hear gunfire. I firmly believe they could have protected those people and the place would not have burned.”

Sheriff Moran, who remained at his home during the riots, was present at the news conference but did not make a statement. Afterward, he declined to talk with reporters.

Contact Rachel Crosby at rcrosby@reviewjournal.com or 702-387-5290. Follow @rachelacrosby on Twitter.

READ MORE:

• Police rebuild trust in Las Vegas’ Westside, one event at a time

• 25 years after the Rodney King riot, west Las Vegas ‘stuck in time’

Rodney King's appeal for calm

Rodney King famously emerged from seclusion on Friday, May 1, 1992, to plead for calm after three days of violence that spread around the nation:

"It's just not right. It's not going to change anything. Let's try to work it out. We'll get our justice. They've won the battle, but they haven't won the war. We'll have our day in court, and that's all we want. People, I just want to say, you know, can we, can we all get along? Can we get along?"

The toll in Los Angeles

Fifty-five people died, more than 2,300 were injured, and more than 13,000 were jailed. Property damage topped $715 million after more than 10,000 businesses burned, creating smoke plumes so thick that planes couldn't land at LAX. The National Guard was deployed, and curfews were instituted.

It was not all violent. But it was volatile. Thousands marched in Los Angeles and cities around the country, peacefully protesting the verdict and police brutality.