Appointees to key positions in Nevada remain little-known to taxpayers

CARSON CITY — Nevada's Public Employees Retirement System, with more than $34 billion in assets, is overseen by a panel of seven public-sector workers appointed by the governor.

But as a recent nationwide report from the Center for Public Integrity and Global Integrity pointed out, Nevada taxpayers don't know much about the individuals charged with managing the state retirement system for nearly all state and local government employees.

The same is true for appointees to other boards and commissions, from the state Board of Transportation to the Board of Medical Examiners to the Board of Education.

Casino executive Elaine Wynn, for example, is not required to file a financial disclosure as president of the state Board of Education. None of the other appointees must file either.

The appointed members of the Transportation Commission, who recently voted to award a $559 million contract for the Interstate 15 project called Project Neon, also do not have to disclose potential financial conflicts on the forms.

And possibly the most ironic: Members of the state Ethics Commission are not required to file disclosure statements.

The reason: Nevada law only requires appointees to such boards to file financial disclosure statements with the secretary of state's office if they earn $6,000 or more in salary in the positions. Most appointees in Nevada earn a paltry $80 a meeting.

Yet these appointees wield influence over a wide range of policies and public tax money, such as PERS, with its billions of dollars in investments.

All the state appointees to boards and commissions must follow the state ethics laws that govern disclosures and voting. For members of PERS, there is also a fiduciary responsibility spelled out for members.

But as for disclosure of financial interests, Nevada has no such requirement.

Some see need

Tom Skancke, appointed in 2013 to the Transportation Board by Gov. Brian Sandoval, said he has disclosed all potential conflicts even if the business relationships are more than a decade old.

"In my own personal opinion there needs to be more reporting," he said. "If I had to disclose my stocks, I would not have a problem with that. I'm not certain it's important or relevant for an appointed member of a board or commission to have to disclose their net worth."

Skancke said Nevada also needs more lobbyist disclosure, another area in which the center's 2015 State Integrity Investigation report found the state lagging. When he lobbies for a client in Washington, D.C., Skancke said he has to report who is paying him and for how much, and that entity has to file a similar report. That is not the case in Nevada.

Mark Vincent, chairman of the PERS board, said he would have no issue with having a disclosure law for appointees to boards and commissions.

"That would not bother me at all," he said. "Speaking for myself personally, there is an opportunity to strengthen the disclosure laws throughout the state, including at the local government level."

Vincent, a city of Las Vegas employee, said that in the mid-1980s some appointees to the PERS board made what turned out to be bad investments.

In 1987, the Legislature changed the makeup of the board, requiring that all members be public employee participants. Vincent said disclosure requirements might have helped reveal the private interests in that case.

Ethics panel receptive

Yvonne Nevarez-Goodson, executive director of the Ethics Commission, said the panel would be receptive to any effort to increase transparency in financial reporting requirements.

"I don't know where the $6,000 threshold even came into being, but I'm not sure there would be a lot of resistance from any public official who would be asked to file the document," she said.

Another form is required to be filed with the Ethics Commission by public officers who represent private clients before an executive branch agency. That form could be folded into an expanded reporting requirement, Nevarez-Goodson said. But there is no way to know if all individuals are submitting the forms because there is no way to monitor compliance, she said.

"It seems like recent stories and concerns may provide a ripe opportunity this interim and the next session (of the Nevada Legislature) to strengthen and enhance public integrity issues and the commission is committed to such efforts," Nevarez-Goodson said.

Some appointees, such as members of the Public Utility Commission and the Gaming Commission, do report because they earn more sizable salaries.

Sondra Cosgrove, president of the League of Women Voters of Las Vegas Valley, said it might be time for a review of the reporting requirements.

"Twenty or 30 or 50 years ago it wasn't a big deal to do things this way," she said. "The money was not so significant. Everyone knew everyone else. But then we got really big, really fast, and we never went back to consider what we need to know about people who are managing a billion dollars.

"We are playing for higher stakes now, and so the question is, do we need to do things differently?" Cosgrove said.

Who leads charge?

Making the reporting requirements more inclusive would require action by the Legislature, but good government and transparency bills often fail to win approval or end up as shadows of their original intent.

UNLV political science Professor David Damore said the issue is ripe for review, but he questioned who would lead the charge for change. There is no incentive for the executive branch to seek changes, and the Legislature has but 120 days every other year to address a large number of issues, he said.

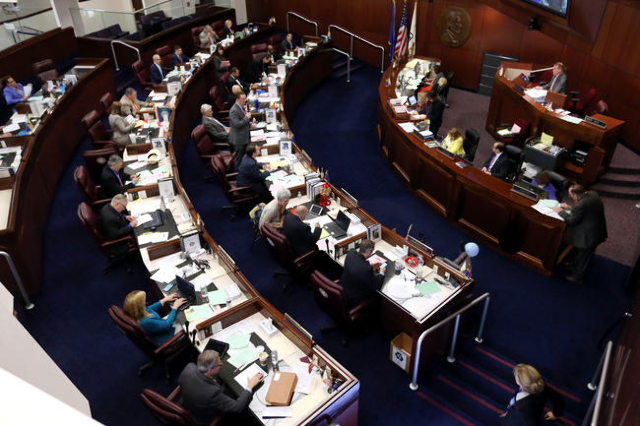

The part-time Legislature also means there is little oversight of state boards and commissions though they make major decisions about important aspects of state government, Damore said.

A lack of transparency fosters government mistrust, he said.

"There is the perception that government is sort of above the law," Damore said. "There is talk about transparency, but we don't see anyone doing anything."

While bolstering the reporting requirements could shed more light on decision makers, there is also the question of the state form itself.

Nevada's form, which all elected officials and candidates are required to file, is vague. Nevada property must be disclosed, but no values are given. And those filing only have to list properties in "adjacent" states. Sources of income must be reported but not dollar values. Gift reporting is also required in some cases where values exceed $200.

Required in other states

The National Conference of State Legislatures shows a state-by-state comparison of disclosure requirements, and many states require a range of values of property and sources of income. So do the federal financial disclosure forms.

A national report using 2013 data ranked Nevada 33rd of the 50 states for quality of conflict-of-interest laws. The Better Government Association's BGA-Alper Services Integrity Index said, "Indeed, if this index reflects one major trend, it's that too many states are dismissing or ignoring the public's right to know."

The report found that 47 states require state-level public officials to file financial disclosure forms, but few require detailed information.

While Nevada's disclosure forms are easily accessible on the secretary of state's website, there is is no budget to check for compliance.

Wayne Thorley, deputy secretary of state for elections, said that, while there is no compliance budget, the agency would investigate a specific complaint, if filed.

Contact Sean Whaley at swhaley@reviewjournal.com or 775-687-3900. Find him on Twitter: @seanw801