Geologists urged to speed collection of fault data

With every small rumble that triggers their seismographs, Nevada geologists inch closer to understanding hazards posed by earthquake faults in the Las Vegas Valley.

There's no time to waste, they say, because they need to collect the data before the valley gets more covered with houses, buildings and roads.

And there's a lot of ground to cover before those locations are paved over.

Little earthquakes happen often, like the one Thursday, a magnitude 1.8 near Henderson.

And ones like the 4.8-magnitude jolt in May near Caliente that knocked loose a rubber insert on a freeway ramp 75 miles away in Las Vegas — and shut down part of the Spaghetti Bowl for several hours — are proof that faults in the area are still slipping like they've done for millions of years.

As they continue to release strain from deep in the earth, the crustal surface above them moves as well. This stretching of the crust, from blocks of rock shifting along fault lines, results in expansion of the basin.

But the next fairly sized temblor could knock more loose than a piece of rubber on a freeway. Instead, damage might soar into the billions of dollars.

Conservatively, hundreds of millions of dollars in damage could be expected, Craig dePolo, an expert from the Nevada Divisions of Mines and Geology, told a gathering of scientists and engineers on Tuesday.

"A magnitude-6 in Las Vegas Valley is a $3 billion event. ... A magnitude 7 — and that really would be the max for this basin — would be upwards of $21 billion," he said, based on the length of the faults and their proximity to structures.

"For Nevada's economy ... what a hit this would be. So it's serious we get this right," dePolo said in his presentation for the 25th anniversary meeting of the Southern Nevada Section, Association of Environmental and Engineering Geologists.

Magnitude is a measure of the strength of an earthquake, or the energy from strain that's released from it. Strain from movement of tectonic plates and large rock masses can build up along a fault until it slips or snaps like a pencil that someone bends at both ends until it breaks, releasing energy.

A magnitude-3 earthquake is like a chunk of a rock layer the size of a football field rupturing.

Covering the ground

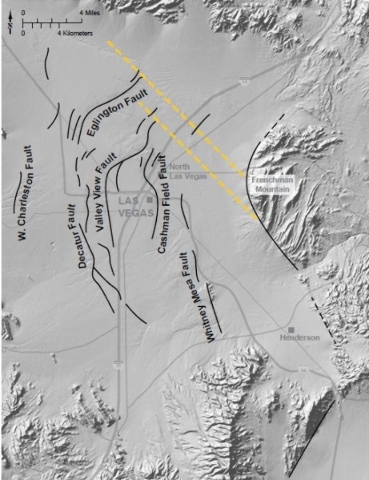

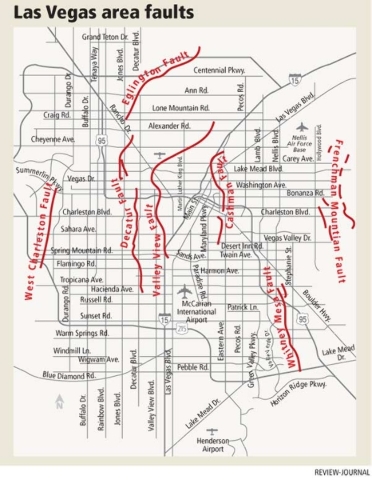

Most of the clues about what's going on with the complex system of at least 11 faults that cross the valley's floor or extend beyond it are found in the soils at trench or drill sites.

The effort to dig further to complete maps and models is hampered by what dePolo calls "the Los Angeles mode," where much of the valley has been built over.

Because of this lack of data, the current understanding of the valley's earthquake threat "is weak," he said.

"Scarps," or steep soil banks that poke from the surface, are most evident along the Cashman Field Fault, where it crosses Bonanza Road near Maryland Parkway, and the 35-foot-tall Decatur Fault scarp on Alta Drive, between Easy Street and Falcon Lane.

A powerful quake along the 14-mile-long Decatur Fault or others in the basin could hit at any time: tomorrow, a hundred or a thousand years from now or thousands of more years into the future, scientist predict.

They believe the Eglington Fault at the north end of the valley was slipping at a fairly fast clip in geologic terms 18,000 to 22,000 years ago, resulting in a combined 45 feet of offset, or displacement of the rock layers.

Nevada ranks third behind California and Alaska of the states with the most large earthquakes over the past 150 years.

Southern Nevada has had a higher rate of tectonic activity during the past 15,000 to 25,000 years, said dePolo, an earthquake hazard expert. His mentor, retired UNR Professor Emeritus D. Burt Slemmons, 92, of Las Vegas, an internationally recognized geoscientist, also spoke at Tuesday's meeting.

The largest earthquake that scientists expect to occur on faults near Las Vegas would be more than 1,000 times less powerful than Japan's catastrophic 9-magnitude earthquake in 2011 that killed more than 10,000 people.

Unlike the state's biggest recorded earthquake that struck a sparsely populated part of Northern Nevada 100 years ago this month — 7.3 magnitude — one that could rock the Vegas cityscape would be devastating.

A computer model by the Nevada Bureau of Mines and Geology shows that if a magnitude-6.6 quake struck on the Frenchman Mountain Fault, there would be 200 to 800 fatalities, 3,000 to 11,000 people would need shelter and there would be major damage to 30,000 buildings in and around the Las Vegas Valley.

The projected economic loss for that one would be between $4.4 billion and $17.7 billion.

Hotels and resorts on the Strip and throughout the valley are required to meet or exceed earthquake safety guidelines in the Uniform Building Code and the International Building Code. Seismic designs for buildings are not solely related to earthquake magnitudes but how a structure performs while the ground is shaking, and how it rides out motion.

Hazard perspective

"We are teaming up in what we hope is an accelerated effort to understand these faults," dePolo said, referring to geoscientists from UNLV, the Nevada Bureau of Mines and Geology, and the U.S. Geological Survey.

The seismic risk in Las Vegas, of course, is lower than Los Angeles, where the southern segment of the San Andreas Fault looms.

In an email to the group's vice chairman, Nick Saines, dePolo noted that Las Vegas has about a 12 percent chance of having a magnitude-6 earthquake within 50 years and within 31 miles.

"That is a pretty low probability," he wrote. "People take actions for earthquakes because the consequences are unacceptable, not because of the probabilities of an event. That is why the Clark County Building Department, one of the finest in the country in my mind, uses the most up-to-date seismic provisions in the building codes."

Contact Keith Rogers at krogers@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0308. Find him on Twitter: @KeithRogers2.